Victoria Valle Remond

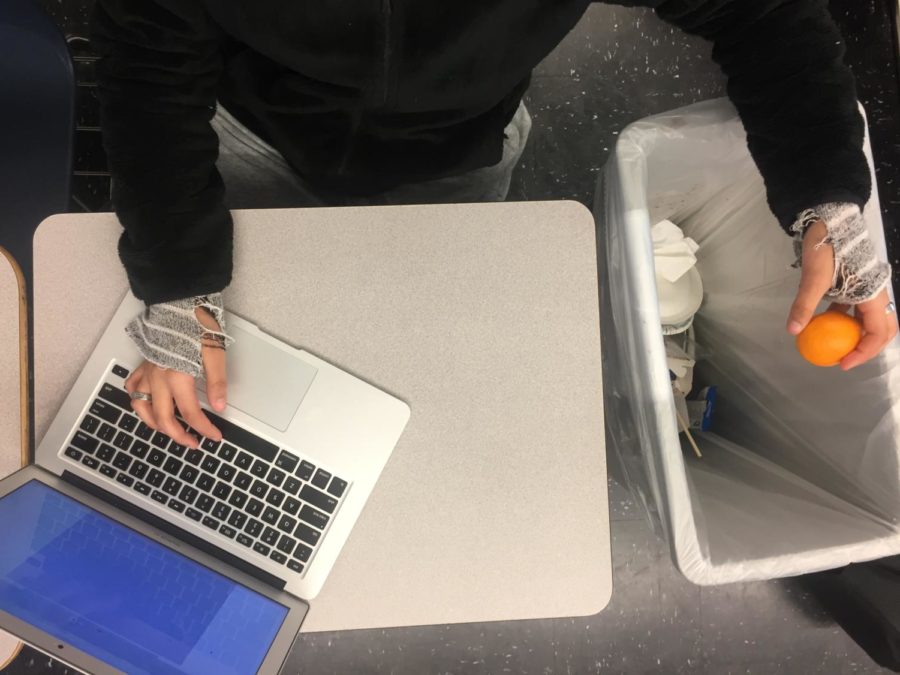

Students, such as Reign Miller, often find that they don't have time to eat and instead use lunchtime to do work.

The alarm clock rings. Sophomore Reign Miller wakes up and gets ready for school. Her family members eat breakfast, but she doesn’t – there’s not enough time, or she’s not hungry.

Fast forward to four hours later: the lunch bell rings. Some students take out a bagged lunch, while others wait in line to buy a meal.

Most days, Miller doesn’t eat lunch. It’s not on purpose, she’s just usually busy doing work, or the line is too long.

Chances are, Miller won’t eat a full meal again until dinner, more than five hours later.

“I never have time to eat before I leave for school, and school starts really early, which means my appetite isn’t prominent yet,” Miller said. “I usually try and use lunchtime to get ahead in my classes or my homework, so I don’t really have the time to eat.”

Miller is not the only teenager who eats close to nothing for nearly eight hours.

She and many others who skip meals during the school day will inevitably get hungry, which is when it begins to conflict with academic performance and affect their health.

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), hunger due to insufficient food intake is associated with lower grades, higher rates of absenteeism, repeating a grade, and the inability to focus among students.

Such studies show that eating breakfast and lunch is vital to student performance. A student who hasn’t eaten for eight hours is likely to perform at a lower level in class than a student who has already eaten.

A study by Cardiff University in 2015 suggested that compared to those who start learning on an empty stomach, children who eat breakfast before school are twice as likely to score highly on tests and assessments.

This, in turn, affects all aspects of complete student development; it all starts with the proper intake of nutrients.

Nutrition deficiencies affect cognitive development and can have long term-negative effects.

This is emphasized by a study from the CDC. According to the CDC, skipping breakfast is also associated with a gradually decreasing cognitive performance among students.

Not all students who skip meals stay hungry for the whole day, however.

Some students eat snacks during passing period or class, but that presents a different problem. Sweets or unhealthy snacks become a student’s only source of energy during the school day.

“It’s not like I don’t eat anything at all the entire day,” said Miller. “But usually if I happen to eat a snack during the day, it’s probably not as healthy as a regular meal would be. And it’s not as filling because it’s not as nutritious.”

To combat unhealthy meals in schools and raise awareness about how to maintain a healthy student body, the law requires that high school students receive nutrition education.

This is part of a national model called, “Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child,” which expands on the CDC’s coordinated school health approach.

“As part of the eight core components developed by the CDC, students receive health education and physical education,” said Dr. Karen Li, the wellness coordinator for the Sequoia Union High School District. “Health is academic and it begins with nutrition education.”

The intention is that the presence of all these components in a school environment will deem students as “Fit, Healthy, and Ready to Learn.”

While food is provided and accessible, they can’t force students to eat, and that’s the problem.

Because they don’t eat these two vital meals, they spend an eight-hour day without the necessary nutrients, impeding them from learning at their maximum potential.

According to a 2005 study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Undernutrition leads to deficiencies in specific nutrients, such as iron, which has an immediate effect on students’ memory and ability to concentrate.”

To provide students with balanced lunches that contain all necessary nutrients, high schools in the U.S. have dietary restrictions on the food allowed to be sold on campus.

These nutrition standards are set based on a collaboration between the CDC, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Food and Drug Administration.

According to the CDC, foods and beverages provided through school breakfast, lunch, and after-school snack programs must meet certain nutritional requirements to receive federal reimbursement.

The restrictions are divided into tiers, according to CDC.

Tier 1 specifies food that may be sold to all students of all grades, while Tier 2 refers to foods that don’t comply with Tier 1 and may only be sold to high school students after school. The latter includes sports drinks, ice cream, and caffeine-free soft drinks.

However, this shift in school nutrition doesn’t mean that all students take advantage of such programs.

Many students find that it is better to make a lunch at home or buy a pre-made one.

“To me, it’s a lot more efficient to bring a lunch to school instead of buying one,” said sophomore Jenna Teterin. “It’s faster, and if I’m carrying it around with me, I don’t have to deal with long lines. If I pack a healthy lunch from home, I make the dietary choices that are right for me.”

Regardless of the nutrition reforms implemented in high school lunch programs, students continue to not eat lunch or breakfast and start an eight-hour day on an empty stomach.

Changing this begins with initiatives such as “Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child;” by expanding nutrition education and teaching students the repercussions of skipping meals throughout the school day, schools can hope to make a deeper impact.