Despite the shared ethnic background that supposedly defines culture, a discernible language and culture disparity found between American-born Chinese and Chinese-born immigrants appears to create a rift in the Chinese experience.

American off the Boat

A deep dive into the modern dichotomy that divides American-born Chinese students and mainland-raised international students.

December 14, 2022

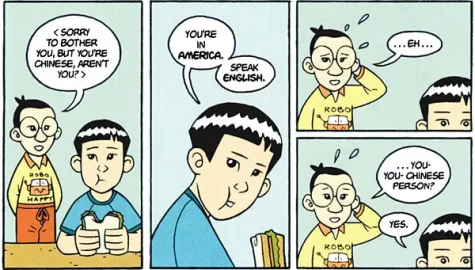

Two acronyms are often used to describe the groups that make up the Chinese population in America: “ABCs,” or American-born Chinese, and “FOBs,” or Fresh off the Boat.

Even though they appear to be simple 3-letter acronyms, they actually have immense significance in the connotations behind the labels.

FOBs are often characterized as newly arrived immigrants who speak “broken” English. They speak Chinese on most occasions and keep close to those who share the same first language. On the other hand, ABCs are often viewed as “Americanized,” detached from their heritage, and often have trouble speaking fluent Chinese.

Despite the shared heritage, many Chinese people residing in the United States observe a growing schism between the two groups.

Susan Wu, president of the International Club at Carlmont High School, attests that the language barrier was a key factor in her struggle to assimilate into American society as well as a potential roadblock in the building of relationships between ABCs and FOBs.

“My cousins are Chinese Americans. They say that it’s especially hard to make friends with Chinese international students because they have their own friends too. I think this is because Chinese international students can’t step out of their comfort zone; they want to speak Chinese to their friends. The Chinese Americans want to speak English,” Wu said.

Wu has noticed certain stereotypes throughout her experience in America.

“For international students, I think the stereotypes are that they are weaker than native-born students because their family has weaker social networks,” Wu said.

Wu seeks to help create connections between international and local students alike.

“I think people tend to isolate international students or make fun of them. One of the purposes of my club is to provide a place for the international students to find a sense of belonging and to make friends,” Wu said.

As president of the Chinese Culture Club at Carlmont High School, Katherine Yu shares similar sentiments about the presence of a cultural discrepancy in different generations of Chinese immigrants.

“This ties into some topics like cultural appropriation, where people living in Taiwan or China might not feel very offended about that sort of thing. But if you’re living here, because the people around you are the ones that would make fun of you for that sort of thing, it just impacts you a lot more,” Yu said.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, culture can refer to “the set of norms, practices, and values that characterize minority and majority groups.” However, the striking differences that separate the American-born Chinese from those who immigrated to the states now test the relevance of the modern definition of “Chinese culture.”

To get the full picture of how Chinese American culture emerged from “traditional” Chinese culture, one must take a closer look at how Chinese people arrived in the United States.

The history of Chinese immigration to the United States

The history of ethnic Chinese people is often categorized into four major waves, dating back as far as the 1850s with the discovery of gold in California, according to Al Jazeera plus (AJ+), a social media publisher owned by Al Jazeera Media Network.

As the development of the Transcontinental Railroad kicked off, railroad companies realized the demand for a bigger labor force, presenting the perfect opportunity for Chinese laborers to escape political instability and chance upon economic success, according to History.com.

However, as workers from China flocked to California in search of jobs, white laborers felt that the growing Chinese populace was a threat to their economic opportunities due to their numbers and the low wages they were willing to work for.

These concerns ultimately manifested into the implementation of discriminatory laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred the immigration of Chinese laborers to the states for over 60 years. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first act to target an ethnic group in the scope of immigration.

The population of Chinese people in America undoubtedly took a downturn due to the restrictive immigration law until its repeal in 1943, kick-starting the second and third waves of Chinese immigration, according to AJ+.

In the years between 1950 and 1960, the Chinese population in America doubled, and the incoming immigration pool had shifted from mainly blue-collar workers to white-collar workers and their families who sought to pursue higher education.

Yet as the Chinese populace in America established itself as a part of United States history, it became evident that the similarities between fifth-generation Chinese Americans and recently arrived “fresh off the boat” continuously dwindled.

Chinatown’s unique aesthetic, for example, is not an accurate reflection of any real cities in China, nor China’s real culture.

Rather, the birth of this new culture was a survival strategy practiced by Chinatown residents to preserve their land by appealing to a more exoticized interpretation of their cultural architecture.

Despite the distinctions that draw certain boundaries between the Chinese American and “fresh off the boat” experience, one aspect of American living has affected all Chinese people residing in America alike: racism.

Regardless of their numerous differences, ABCs and FOBs have shown unconditional solidarity and support for one another in times of need. For example, organizations such as Unified Asian Communities (UAC), which operates in Maine, held local vigils and organized rallies and mutual aid funds for victims of racist attacks.

The bonds of the Chinese community only strengthened after the uptick of anti-Asian hate crimes in America as all Chinese residents rallied behind the movement to “Stop Asian Hate.” Chinese American journalists and activists were quick to speak up for those who could not express themselves in English, especially the elderly who fell victim to racially motivated attacks.

“Through UAC’s presence, I hope groups of people from various backgrounds, different ethnicities, different cultures all come together to share knowledge and resources so that everybody gets their needs met, feels that they belong, and are empowered,” said Amy Chea, secretary and chief strategy officer of UAC.

The modern divide

Regardless of the cultural differences, both ABCs and FOBs contribute to what now constitutes the Chinese identity in America.

Both Wu and Yu shared that their experiences of living in America impacted their ties with family.

“One thing that people don’t know about international students is that their parents are usually not home, they’re in another country, so their parents support them financially, but international students may lack the company of their parents,” Wu said.

Despite her differing experiences, Yu shares kindred sentiments with Wu.

“All my relatives live in Taiwan. Sometimes my family has felt a little bit isolated without a support system,” Yu said.

Peiyi Wang, a graduate student at UC Irvine’s School of Social Ecology, analyzed the roots of this transformative culture development through a psychosocial lens.

“Foreign-born individuals may be more likely to employ the separation acculturation strategy (high identification with heritage culture and low identification with the U.S. culture), whereas U.S.-born individuals may be more likely to use the assimilation acculturation (low identification with heritage culture and high identification with the U.S. culture) or integration strategies (high identification with both cultures),” Wang said.

The cultural divide between ABCs and FOBs is not just a phenomenon found in the Chinese immigrant population. The complex nature of intra-ethnic relations continues to evolve with the ever-changing demographics of the United States.

Often considered a “nation of immigrants,” the heterogeneous constitution of America has transformed many ethnic groups’ ties to their culture.

The celebration of heritage and diversity has progressively developed into a principal feature of the American lifestyle, one that may appear confusing or even arbitrary to countries with longstanding homogenous cultures.

However, according to Pew Research, more than six-in-ten Americans believe that the racially diverse U.S. population has a positive impact on the country’s culture.

Appalachian State University’s Diversity Celebration cites many reasons for the significance of recognizing diversity, including its ability to “foster respect and open-mindedness for other cultures, unite and educate people, understand other’s perspectives, and broaden our own.”

From the subject of diversity in the workplace to dinner conversations with one’s grandparents, the presence of multifaceted perspectives and experiences seems to perpetually loom over us.

Despite the frustrations that may accompany this lack of cohesion between groups, there are many benefits associated with encountering new cultures, like acquiring a fresh outlook on one’s own heritage or learning about a completely novel culture.

Wang believes that promoting cultural identity and biculturalism among Chinese Americans and international students could be beneficial in feeling more integrated with their heritage rather than conflicted.

“Via the experience of staying in another culture, individuals may be better able to adapt to new situations, develop more effective coping methods, and create new identities that assist them in navigating other cultures and societies,” Wang said.