Twitter: @camilllllle__

Animal use in schools incites ethical debate

March 26, 2023

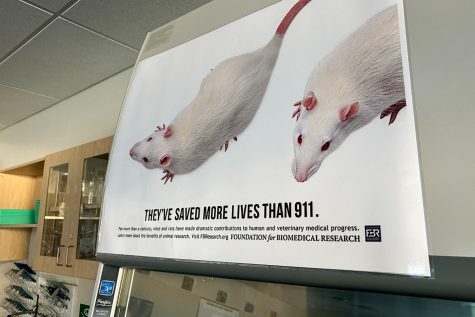

A mouse lives in a cage at Stanford University.

It has an altered genome, explicitly bred for animal research in labs.

Universities often purchase these mice from laboratories regulated by the United States Department of Agriculture, like the Jackson Laboratory, which breeds thousands of mice models with different genotypes for research.

After the mice are purchased, they journey to their new homes in germ-free containers to universities like Stanford.

A cool breeze touches their fur as researchers individually put them into air-conditioned cages based on their weights. Their water bottles are next to them.

If the mice have family in the lab, they live with them, while aggressive animals, like monkeys, are separated from each other to prevent fighting.

Veterinarians and anesthesiologists carefully check the animals for diseases and monitor their diets because unhealthy and sick animals can negatively affect research.

Animals are also used in the curriculums of biological science classes to aid learning. Students dissect animal organs and study other small faunas like pill bugs and brine shrimp.

While animal use is necessary to make new medical discoveries, like vaccines, it raises ethical concerns and moral questions for students and researchers: Do the benefits justify continuing the practice?

But before research starts, researchers must first pass an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) composed of scientists and veterinarians, explaining the purpose of their study and what will happen in the process.

“It’s important to make sure you’re using the simplest evolved species. Don’t use a dog or cat if you can use a rat or mouse. Don’t use a rat or mouse if you can use a fish,” said Linda Cork, former head of the Department of Comparative Medicine at Stanford University. She was a veterinary pathologist in charge of the research animals at the university and worked with dogs.

According to Cornell University, the majority of animals used in research are rodents, but other species such as guinea pigs, rabbits, cats, dogs, pigs, cattle, sheep, horses, poultry, amphibians, avians, and aquatic species are used. Many of these animals share a majority of their DNA with humans.

Labs aim to limit animal testing while continuing valuable research through other models like computer simulations, but the human body is so complex that animals are often the only option because of their genetic similarities.

After a researcher selects their animals, they conduct their study. Universities nationwide practice animal testing for research under regulations such as the Animal Welfare Act and those by the National Institute of Health, and throughout the experiment, the IACUC conducts unannounced inspections of animal facilities to enforce the well-being of research animals.

“You can’t deny entry to the inspectors and be like, ‘Oh I need to clean the bathroom,’” Cork said.

At the end of a study, different animals have different outcomes.

“The dogs are put up for adoption. The rats are bred in the facility for the purposes of being tested on, and at the end of the experiment, they are euthanized,” said Sara Shayesteh, a Carlmont biology teacher.

Some animal research leads to worthwhile discoveries.

To figure out how human bodies responded to COVID-19, scientists genetically modified mice and bred them to have human cells that responded to the virus. Their bodies grew weak, similar to how humans react to symptoms. This research helped lead to the development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

However, according to Hank Greely, a Stanford law professor specializing in the ethical, legal, and social issues in bioscience research, most animal research doesn’t lead to anything useful.

In addition to labs using animals to find medical breakthroughs, high school and college-level bioscience classes often use animals to support learning by studying them.

Carlmont’s human biology classes purchase specimens from a local butcher, Costco, and Bio Corporation to dissect for labs.

The classes dissect chickens, sheep brains, frogs, and cow eyes to study animal systems and learn from them.

“The pictures of the anatomy of different species are not going to be exact,” said junior Natalie Su, who took human biology. “Especially for the cow eyeball and the sheep brain, the dissections were helpful for seeing where everything was. In the pictures, it’s hard to see through the layers.”

Regular biology classes used to perform dissections, but because of a shift in curriculums, the human body is no longer a standard, so dissections are no longer necessary.

“I think using animals in the way that we use them now, we try to use them as a way to engage students,” Shayesteh said. “When we worked with rolly pollies or when we work with brine shrimp, I’ve never had anybody not want to participate.”

Animal use can affect people’s decisions in what they do with their lives.

Shayesteh was in research before she switched to teaching.

She started working with cells and then moved to larger organisms.

“Once I started working with rats, rabbits, and dogs, I started to not enjoy that at all,” Shayesteh said.

It was hard for her to do experiments on animals, so she opted out of doing them after she tried them out and became a teacher.

While Shayesteh found herself unable to continue research, many of her colleagues did continue, and she understands the importance of animal research.

As Shayesteh was uncomfortable testing on bigger animals in labs, thinking of different animals in laboratory conditions implicates different things for people.

Groups like the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) oppose all animal use, including the use of smaller animals.

“There’s no reason why any student should be asked to cut up a dead animal for a grade,” said Bridget Dillon, a youth campaign coordinator at PETA.

For others, a line is drawn somewhere in the middle based on the types of animals and the nature of the experiment.

“It depends on how much pain, suffering, and death you’re inflicting on what kind of organism for what purpose. If the research is meaningless, any harm is unethical,” Greely said.

Cultural values also contribute to a person’s willingness to support animal use in research.

“For people from India, cattle research would be shunned because cattle are very culturally praised and religiously special,” Greely said.

Others believe that the benefits of animal use make it worthwhile because it assists learning.

“It’s very beneficial to learn how to do dissections on animals rather than just watching a video on it, especially for people like me who want to pursue a career as a surgeon,” said Jacob Viduya, a freshman studying biology at the College of San Mateo.

For some people, research with animals regarded as pets, like dogs or cats, is a challenging thought.

“I think it would be really hard for me, knowing how intelligent dogs and cats are and how much feeling they have would really impact the way I feel and the way I would learn…If I had to, I could probably work around it, but I would have some objection to it,” said Jack Clark, a senior at Bellarmine College Prep who’s thinking about majoring in pre-med in college.

Those who have worked in an animal facility with board-certified veterinarians know that others have misconceptions about what happens behind closed doors.

“Most people think that animal research is all pain,” Cork said. “Two-thirds of it doesn’t cause any pain whatsoever. There’s about one-fourth that does cause some pain and we’ll use anesthesia so the animal isn’t distressed.”

The rest of animal research does cause pain, but anesthesiologists don’t give animals anesthesia because it can defeat the purpose of the experiment.

The ethical debate surrounding animal use comes down to factors including: the benefits, what animals are being used, and the well-being of animals. Many people settle on some sort of middle ground that aligns with their morals.

In the future, animal use is set on a path toward reduction and efficiency to better align with people’s ethics.

All labs use the 3Rs principle with animal research. They are principles of replacement, refinement, and reduction for animal research.

According to the National Centre for the Replacement Refinement & Reduction of Animals in Research, replacement involves accelerating the development and use of models and tools with new technologies to address scientific questions without using animals, refinement involves using new technologies and understanding factors in scientific outcomes, and reduction involves emphasizing important animal experiments that lead to valuable information.

Some hope that animal use continues on this path toward reduction, with PETA aiming for complete removal, while others wish to continue using animals for their benefits.

However, it may require more than merely following these principles for ideal improvement.

“If you reduce the suffering by 1/3, but you end up doing twice as much research, there may be more animals involved,” Greely said.

According to Greely, animal research also aims to improve non-animal models, including computer simulations, in vitro work of taking cells, tissues, or organs, and growing organs to test on and match human systems. PETA proposes alternatives such as synthetic frogs and augmented reality tools.

“We have a whole team of scientists at PETA who are dedicated to bringing those other forms of experiments to life,” Dillon said.

In schools, animal use in classrooms has been changing. Instead of doing bigger dissections, like using animal organs, Shayesteh leads her AP Biology and Biology classes through smaller experiments, like those using pill bugs to study animal behavior and brine shrimp to study salinity levels.

“I think there’s been a shift in the perceived value of doing those types of dissections and trying to figure out other creative ways where you could still get the same benefit but not have to kill an animal to get that benefit,” Shayesteh said.

Curriculums in classes will continue on the track of reducing animal use in the future, just like animal testing.

Animal use provides a complex line between human benefits and human ethics.

“Most research doesn’t lead to life-saving drugs, but some of it does,” Greely said. “If we got rid of animal research entirely, human medicine would suffer. If we got rid of some bad animal research, human medicine wouldn’t suffer.”