Twitter: @ChesneyEvert

Instagram: @chest_knee

January 12, 2021

“Suffering is universal.”

A quote credited to young adult novelist John Green, but one that extends far beyond the pages of a book. We all have our own monsters, under the bed, down the hall, in our heads.

Sometimes, it’s easy to forget that others have them too.

For over 30 million Americans, that monster is an eating disorder, and the battle is lifelong.

The National Eating Disorder Association characterizes these diseases as “serious but treatable mental and physical illnesses that can affect people of all genders, ages, races, religions, ethnicities, sexual orientations, body shapes, and weights.”

Anorexia, Bulimia, and Binge Eating Disorder are becoming exceedingly prevalent. You know their names, or maybe you don’t; that doesn’t stop them from preying on our friends, children, or acquaintances.

They have to fight every day. Let’s do what we can to help.

In a world where “Saturday morning cartoons” have evolved into a constant stream of blue light, television and social media have never had a more receptive audience.

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry states that teens spend up to nine hours on a screen each day, paying with their perception.

Take Regina George. The iconic queen bee of the 2000s. Popular, manipulative, and clad in low rise jeans, she’s perfection in a satirical high school until a ploy to make her gain weight strips her of all her street cred.

Regina obsesses over food, exercise, and her dress size until it’s a punchline.

She’s not alone.

Hannah Montana, Monica Geller, Lizzie McGuire, Maggie Fitzpatrick, Marley Rose.

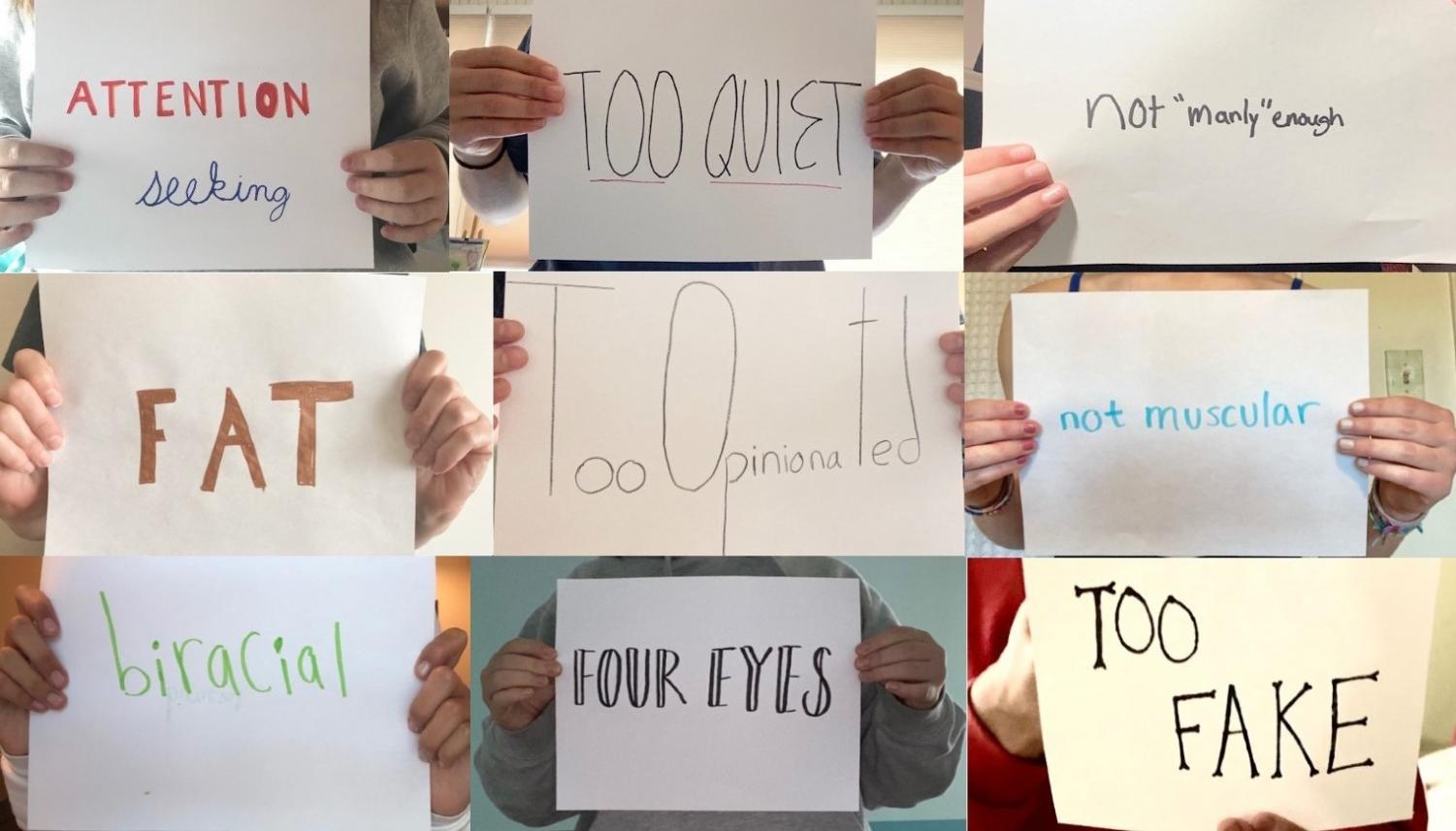

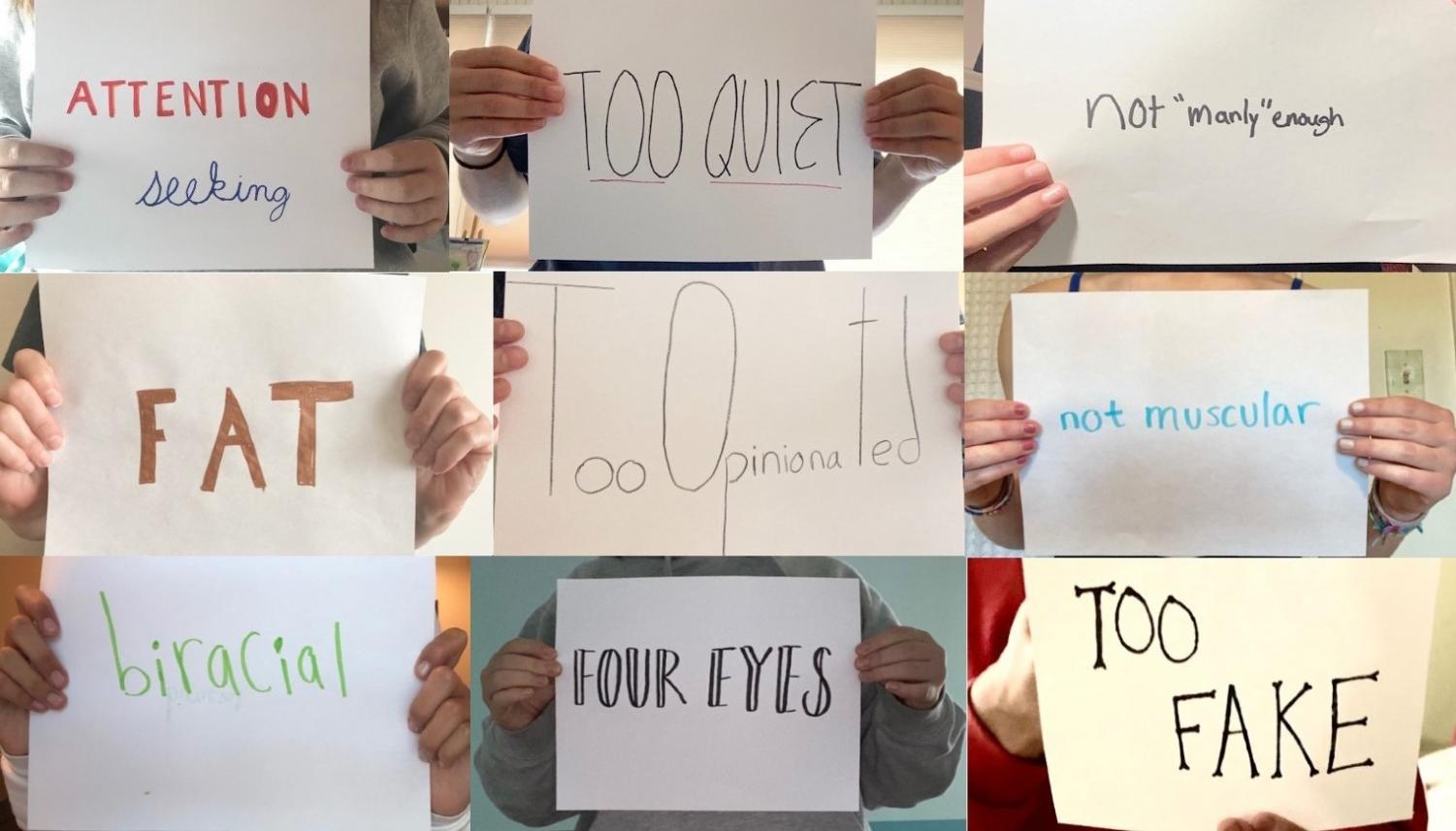

These characters with diet-related dialogue have been on television for years. Whether they’re bullied into skipping lunch or are trying to lose weight to attract the boy next door, they’ve created the stereotypical persona of an eating disorder.

Female, caucasian, heterosexual, thin.

This trope is impressed upon viewers time and time again; teenage girls so focused on obtaining the skinny ideal that they manipulate their food intake to change their bodies.

“I remember watching reruns of ‘The Suite Life of Zack and Cody’ when I was younger,” said Kristie Stevens*, a 16-year-old. “There was an episode; I’ll never forget it; two of the characters were trying to lose weight for a fashion show. Having struggled with an E.D. [eating disorder] myself, I look back and get so angry. […] They made it seem trivial.”

Between pre-recorded laugh tracks, neurological differences become narcissism.

You can’t eat, so you must be obsessed with how you look.

Not only is this woefully incorrect, but it’s also harmful.

Mental illness is not a universally understood phrase. These diseases don’t surface in a cough or sprained limb. They live in the shadows, there, sometimes out of view, but ultimately intangible.

Despite their invisible nature, World Psychiatry reveals that one person an hour dies from an eating disorder, making it the most lethal mental illness.

Many of these fatal cases go undiagnosed.

Liz Motta, the Director of Education and Resources for The Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness, finds that the invalid messages society receives about eating disorders allows many to go unchecked.

“We know through research that eating disorders do not discriminate, yet until the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, one of the mandatory criteria for anorexia nervosa was having a loss of amenorrhea [a menstrual cycle],” Motta said. “This prevented men, a susceptible demographic, from being diagnosed.”

Despite the manual’s previous assumptions, the National Eating Disorder Association states that of the 28.8 million eating disorder cases in the U.S., one-third affect cisgender men.

Gender doesn’t grant men immunity from societal pressures, but it does serve as an obstacle to seeking psychological treatment.

“I think guys today feel so much shame in seeking out help,” said Ben Jacobs*, a 14-year-old in recovery from anorexia. “There is a constant pressure to be strong, and so we hide our feelings.”

The same study showed that people of color and LGBTQ+ community members were more likely to develop certain eating disorders than those with a heterosexual or Caucasian background.

Marginalized demographics carry the weight of systemic injustice from birth, facing unprecedented battles every day. This extra stress and emotional pressure place them at a higher risk for eating disorders and other mental illnesses.

“What we know is that those behaviors regarding food and body are the symptoms, driven by trauma, anxiety, depression, or other factors,” Motta said.

Like many other illnesses, eating disorders also can be passed on through genetics. According to Eating Disorder Hope, a foundation focused on education, having a relative with an eating disorder can make you 7-12 times more likely to develop behaviors.

They are not a choice but a product of circumstance.

“Since I was little, my mom struggled with her own eating habits. She’d skip meals or slowly stop eating certain food groups,” Jacobs said. “Obviously, my eating disorder wasn’t her fault, but we’re family; it makes sense that we have some of the same issues.”

“Everyone hates you, and they want you to disappear.”

You might have heard some form of this once on the playground. Or not at all, if you’re lucky. One time, it can roll off your back.

Hearing it when you eat, sleep, walk, talk, and breathe makes it harder to do that. No matter your mental toughness, you begin to believe it.

For Kristie Stevens*, Ben Jacobs*, and many others, this voice is present at all hours of the day.

Also, there’s no antidote.

“I think we have much more awareness,” said Claudia Stanley*, the parent of a child with an eating disorder. “People know that there isn’t a silver bullet or magic pill […], but we still have a long way to go.”

Beat Eating Disorders, a charity based in the United Kingdom, states that it can take up to eight years to recover from anorexia. Catching it in its early stages can make all the difference.

With this in mind, Motta and The Alliance staff firmly believe that education is the key to prevention.

“So much of what we do at The Alliance is going to doctor’s offices, clinics, and social service agencies because we’re going to see eating disorders in all of these different places,” Motta said. “If they know what to look for, it makes diagnosis more accurate.”

While it’s a good start, education can’t do it alone. However, with representation as its sidekick, the odds begin to change.

Or so believes Dr. Barbara Kessel.

A psychiatrist in Aurora, Colorado, Kessel states that accurate representation of eating disorders in the media could encourage others to speak out.

“If a kid sees that one of their favorite athletes has struggled with an eating disorder and is talking about that openly, other people might realize that a person that they look up to is addressing it, so they can too,” Kessel said.

However, for many, socioeconomic status is an obstacle to receiving the medical care they need.

“Eating disorder treatment is incredibly costly and generally entails an inpatient program, a residential program, a full-day program, and other appointments,” Motta said.

For Inpatient and Residential treatment, patients live in a hospital setting to receive the maximum level of care. A Partial Hospitalization Program (PHP) is a treatment program for a portion of the day, and Outpatient care consists of appointments with care providers.

Access to these services is highly dependent on someone’s financial situation or insurance coverage.

“Without insurance, one day of residential treatment can cost $30,000,” Motta said. “And, there are many people in this country who are uninsured.”

In 2017, the U.S. Census found that 27.6 million people had no form of insurance, barring them from receiving economically sustainable help.

So, what can we do?

Change starts with our choices, but Capitol Hill can make it a reality.

Current legislation surrounding mental health will control access to insurance, resources in schools, and employee protections. Know where your elected officials stand.

Everyone’s experiences are different, and their stories teach us how to make the world a better place; on screens, in schools, or at the dinner table.

It might be a held hand or an “I’m here if you need me.”

A postcard or distraction.

An honest conversation or scheduling a therapy appointment.

“Look, I know these feelings are uncomfortable,” Stevens said. “But until we change society’s view of eating disorders, we continue to push them on other people. How does that make our world a better place?”

*This name has been changed to protect the anonymity of the source, in accordance with Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing policy.