Twitter: arianna_z_news

The importance and progress of coral reef restoration

March 16, 2023

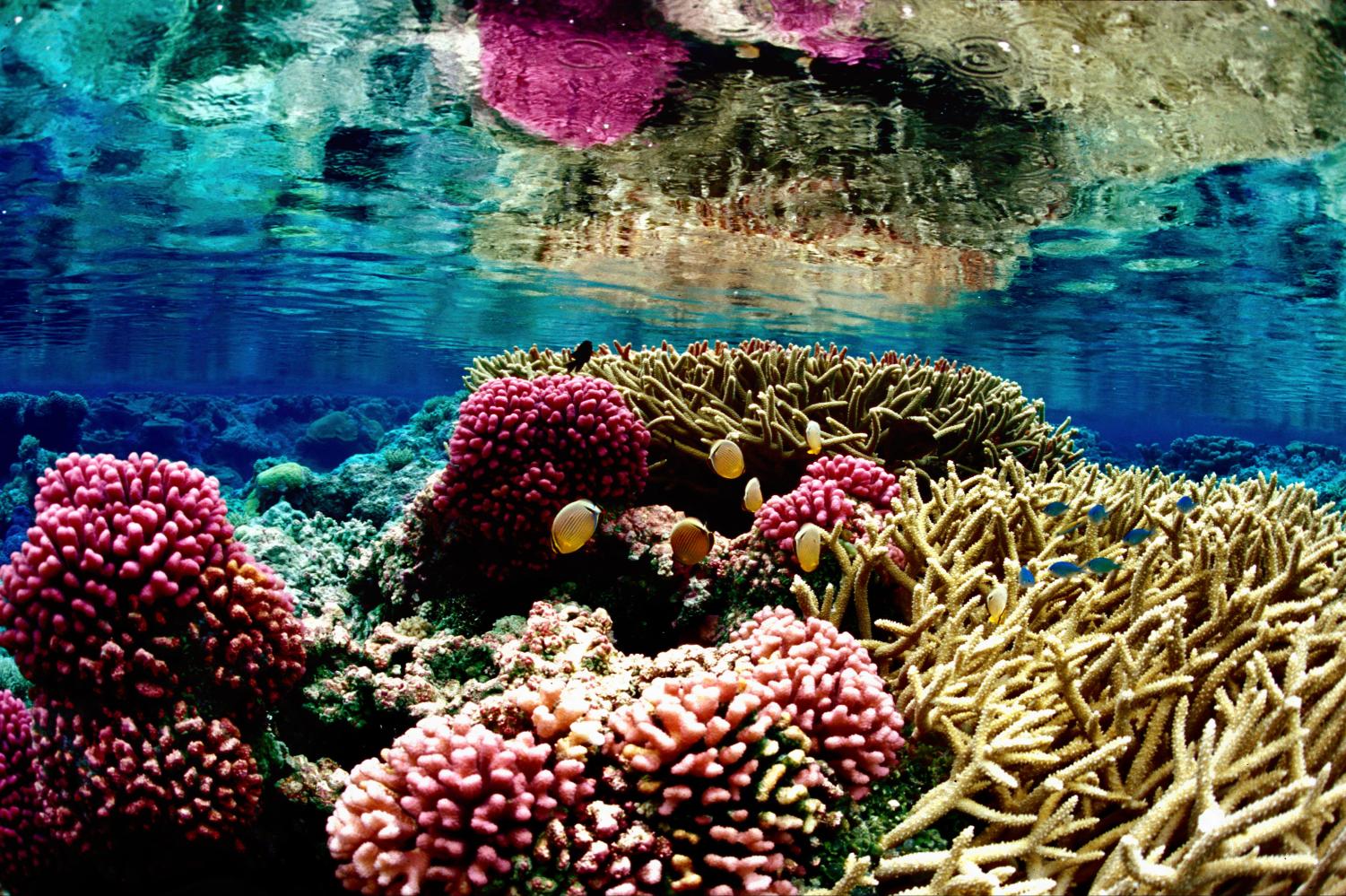

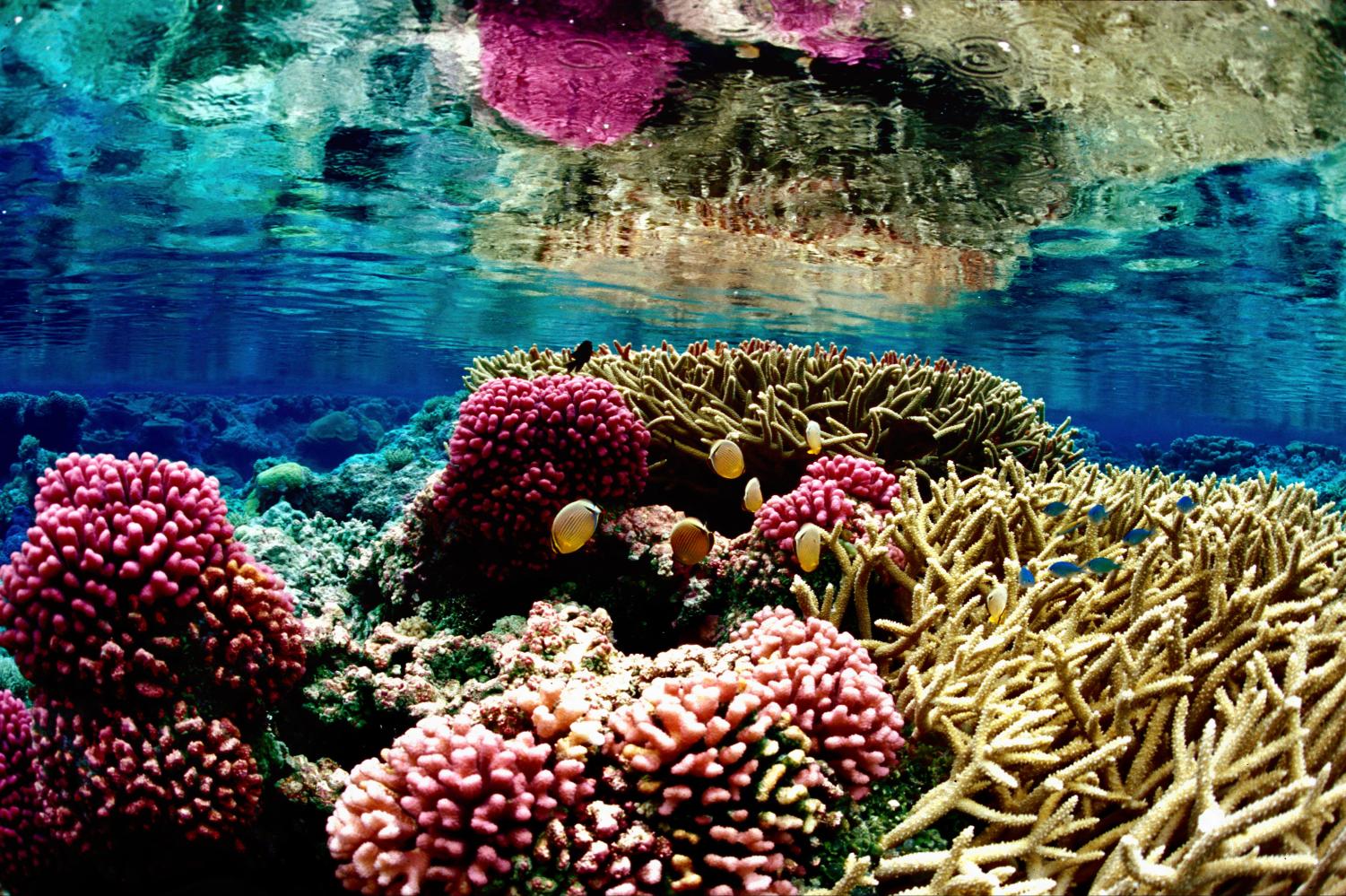

Schools of fish weave through rock-like structures, and a clownfish peeks out from an anemone to observe. A sea turtle swims around looking for food, while a stingray buries itself in the sand to hide from predators. These creatures make up a scene from a typical coral reef before mass coral bleaching started to plague these marine ecosystems.

Today, instead of a vibrant reef ecosystem, one is more likely to see a couple of fish swim aimlessly through a boulder field of white rock—rock that was once kaleidoscopic coral. Below the fish lie dead anemones, and any sea turtles or stingrays that used to inhabit the reef have since migrated.

As climate change persists and ocean temperatures rise, more and more coral reefs are at risk of dying. In 2022, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia suffered its fourth mass bleaching event in 7 years, and that is only one of the hundreds of reefs that have shown evidence of bleaching.

Coral reefs worldwide are suffering from the effects of climate change more than probably just about any other organism on the planet. — Tom Moore

“Coral reefs worldwide are suffering from the effects of climate change more than probably just about any other organism on the planet,” said Tom Moore, director of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology’s (KAUST) Reefscape Restoration Initiative project, located along the Red Sea coast in Saudi Arabia.

When corals become distressed, they lose their colors, a process called “coral bleaching” by scientists. Coral itself is colorless, even translucent. The microbes that live symbiotically within corals give them their color.

However, when the water gets too warm, that symbiosis between the corals and microbes starts to break down, and the coral expels its microbes into the water in a final attempt to survive the warming waters. Once the microbes are expelled, the coral appears to bleach.

It’s important to note that coral bleaching is different from coral dying. In other words, coral bleaching is not always permanent.

“If the water becomes cool again, then there’s typically enough microbes left in the coral to regrow, and the coral recovers. If the water stays warm, then that act of desperation by the coral will not succeed, and the coral will die,” said Mark Hixon, a professor of marine biology at the University of Hawaii specializing in coral reefs.

Scientists consider corals a keystone species because of the many animals and plants that depend on them. Over 7,000 species of plants and animals depend on coral reefs for survival.

“When corals die from coral bleaching, it upsets the delicate balance of marine ecosystems. Many fish and marine organisms rely on corals to provide food and shelter, and when corals are no longer available, it makes it harder for fish species to survive,” said Heather Rowan, the development operations coordinator of the Coral Reef Alliance.

When corals die from coral bleaching, it upsets the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

— Heather Rowan

And it’s not just marine organisms that depend on corals. Over half a billion humans depend on coral reefs as well.

“A lot of money is generated from coral reefs, either through things like fishing on coral reef ecosystems because coral reefs are nurseries for a lot of really important commercial fish species or tourism. For example, in Florida, a lot of tourists want to snorkel and scuba dive in coral reefs,” said Alexis Sturm, who has a doctorate in coral reef ecology and is a science policy fellow for the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force.

In addition to the economic benefits of coral reefs, corals provide coastal protection.

“They’re really important for coastal hazards risk mitigation. If you have a big storm that’s coming, which is also worsened by climate change, corals can act as a type of physical barrier that helps prevent the impact from that storm surge from being so detrimental,” Sturm said.

In areas closer to sea level, such as Florida, which is also prone to tropical storms, coral reefs can buffer coastal communities from the worst impacts of the storm.

If all the reefs disappeared, food, shelter, and spawning grounds for fish and other marine life would vanish, and biodiversity would be significantly diminished.

Benefits of Coral Reefs by Arianna Zhu

Many online sites warn of coral reefs completely dying off within a generation and support that prediction with the fact that a large number of corals have either already died off or are facing severe bleaching.

“Coral bleaching is occurring in tropical areas, mostly because corals prefer a very specific temperature range which favors lower latitudes. Unfortunately, coral bleaching is affecting almost all corals around the world, including the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the Mesoamerican reef and the Caribbean, and the Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia,” Rowan said.

Coral bleaching is affecting almost all corals around the world, including the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the Mesoamerican reef and the Caribbean, and the Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia.

— Heather Rowan

Corals face a variety of stressors that lead to bleaching. Scientists ultimately separate these stressors into two types: local and global stressors.

“So pollution, overfishing, and destruction or sedimentation from coastal development are all local stressors. When it comes to global stressors, we’re talking about climate change, which drives both coral bleaching and ocean acidification, and diseases, like the Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease,” Sturm said.

However, new findings give scientists hope that some corals will survive if they are given time to adapt and adjust to new ocean conditions.

“The projections that we’re going to lose all our coral reefs were exaggerated. We now know that some corals have the ability to acclimate and adapt to a warming, acidifying ocean. The key thing to keep in mind is that there will be winners and losers as the oceans warm and acidify, but we will probably not lose coral reefs entirely,” Hixon said.

The key thing to keep in mind is that there will be winners and losers as the oceans warm and acidify, but we will probably not lose coral reefs entirely.

— Mark Hixon

Scientists have discovered that not all corals respond the same way to changes in climate. Researchers compared staghorn coral with mountainous star coral in a study led by the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. They discovered that staghorn coral was more sensitive to heat stress than mountainous star coral.

Given time, some reefs will be able to adjust to the warming ocean temperatures and rising acidity levels.

“Our scientific research tells us that coral reefs can adapt to the effects of climate change. If we keep corals healthy in strategic, ecologically connected networks around the world, we can create the conditions under which evolution can help rescue reefs,” Rowan said.

Developing technologies have found a way to restore some dead corals. Deemed “coral restoration” by scientists, the technique involves planting small corals raised in nurseries on dead reefs in hopes that it will revive the reef.

“Coral restoration means bringing back reefs that are dead, but it depends on how severely degraded the reef is,” Hixon said.

KAUST’s Reefscape Restoration Initiative Project is one of the world’s greatest coral restoration efforts. It revolves around a 100-hectare reef area around Shushah Island in the Red Sea.

“It’s an interesting site. It’s a mix of really amazing high-quality reef and really heavily degraded reef, and that is a good environment to do one of these test-type projects. Generally, the best thing to do is work from areas that have moderate health and then begin to restore the degraded areas around them,” Moore said.

The KAUST Restoration Initiative began in 2021. Two years later, the organization started its initial restoration phases.

“Based on what we’ve seen of the site and what we understand of techniques elsewhere around the world, we’re pretty cautiously optimistic that we will be able to begin to restore some of the site,” Moore said.

However, with approximately half a trillion corals in the Pacific Ocean and more located in other regions, it’s unrealistic to expect coral restoration to be a cure-all solution to bleaching.

“The idea of restoration and coral reefs is not to restore every single reef that is out there. It’s to provide reefs with enough time to adapt to these warmer conditions and hopefully give the reefs a chance to recover on their own,” Moore said.

It is important to know that coral restoration will only be a permanent solution once we solve climate change.

We need to focus on trying to prevent further increases in the number of bleaching events and coral mortality events by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and then we can focus on restoring what we have.

— Alexis Sturm

“If there’s continued bleaching, then the restoration is not going to do much. We need to focus on trying to prevent further increases in the number of bleaching events and coral mortality events by reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and then we can focus on restoring what we have. It’s a two-pronged approach,” Sturm said.

With the discovery of the adaptive properties of coral and coral restoration underway in various parts of the globe, the future of our world’s reefs is looking brighter.

“Corals are like the rainforests of the sea. They have a certain value intrinsic to them being part of this planet. They are worth saving,” Sturm said.