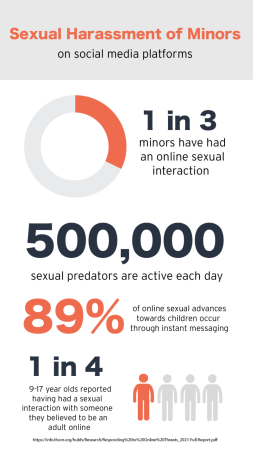

Every day, 500,000 sexual predators scroll through social media platforms, looking for their next victims.

These predators often create social media accounts on platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook to sexually harass children through direct messages (DMs) or inappropriate comments on posts.

“Online bullying and harassment can take many forms, from sending someone abusive messages, to public comments or exposing someone’s personal information,” said Lisa Dittmer, who researches children’s and young people’s digital rights for Amnesty, an international organization that campaigns for human rights.

With just a few clicks, anyone can give themselves a different age and fake profile image, making it easy for sexual predators to create an alternate identity on social media to commit acts of sexual harassment. According to the Child Crime Prevention and Safety Center, over 50% of the victims of these online sexual predators are between the ages of 12-15.

Ainsley Colt, a junior at Carlmont, is one of many teens who has experienced sexual harassment through messages on Instagram.

“This man had in his bio that he was a sugar daddy, and he DMed me and asked if I wanted to be his sugar baby. Then, he sent me a picture of his penis,” Colt said.

With 59% of teens having been harassed on social media platforms at least once, many adults and children are left to wonder what measures social media companies take to protect kids online.

While there are some legal consequences for online sexual predators, which include jail time for sending pornography to minors, many sexual predators are able to keep their true identities hidden on social media, allowing them to commit sexual harassment of children with few repercussions.

“[Social media] companies are failing in this responsibility to address the problem of online violence and abuse, often allowing harassment and violent content to stay online,” Dittmer said.

Although many social media companies have some minor features in place to prevent harassment, including limiting comments and providing a warning when someone posts an offensive comment, 79% of Americans say these companies are doing only a fair or poor job at addressing online harassment or bullying on their platforms.

I think if you asked these platforms if they are taking measures to prevent sexual harassment they would say yes, but the question is really is that enough to protect young people online? It is not.

— Bzu Shiferaw

“I think if you asked these platforms if they are taking measures to prevent sexual harassment they would say yes, but the question is really is that enough to protect young people online? It is not,” said Bzu Shiferaw, who works at Fairplay, an organization committed to helping children thrive in the digital world.

As social media companies fail to resolve the ongoing issue of sexual harassment of children on their platforms, schools and government organizations have taken the initiative to defend children’s online rights.

“Social networks must invest far more resources into keeping their users safe and into designing their platforms so that violent and polarizing content doesn’t get more attention than positive posts,” Dittmer said. “As they have shown they will not do this voluntarily, governments must oblige them to do so by law.”

In California, democratic and republican state representatives Buffy Wicks and Jordan Cunningham introduced the California Age Appropriate Design Code Bill to improve the safety of children in the digital world. After unanimously passing this law on Aug. 29, 2022, the California Senate will now require online companies to consider the protection of minors when designing digital products.

“[Sexual harassment on social media] often leaves people feeling totally powerless and lonely,” Dittmer said. “Learning about children’s rights [and] knowing that you have every right to demand that companies and governments create a safer environment is critically important to making change happen.”

In middle schools around the globe, Diana Graber founded Cyber Civics, a digital literacy program that aims to provide information and activities about harassment, cyberbullying, and privacy online. Many middle schools use this program to educate students about how to safely navigate the digital world.

“Teaching parents about online harassment isn’t enough. We’ve got to teach the kids directly. And that’s why we started Cyber Civics,” Graber said.

Furthermore, a study by Purnama and colleagues found that when educated about digital literacy, students were less likely to experience online risks such as sending or receiving sexual messages, cyberbullying, and meeting in person with someone they met on the internet.

“I think [social media companies] are starting to do more than they used to when it comes to protecting children from online sexual harassment. They could do a lot more, but in the meantime, we can’t sit around and wait for them to change how they operate,” Graber said.