It’s no secret that most Americans – about 60% – support the right to abortion. Yet, the anti-abortion movement is prevalent in our media and government.

Recently, Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion to overturn Roe v. Wade was leaked, catapulting this issue further into the forefront of politics. This ruling would decide Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case that came to fruition after Mississippi passed a 15-week abortion ban. While Alito’s opinion is not final, it indicates a strong possibility of an abortion-less future in some states.

In reality, the anti-abortion movement isn’t about pregnancy but was a well-organized political move thought out by conservative leaders.

This anti-abortion movement is often linked to the conservative right due to white evangelicals comprising a large portion of its voter base. According to Pew Research, 84% of white evangelicals voted for Trump in the 2020 election, the highest percentage of any religious group polled. Evangelical Protestantism also has the third-highest percentage of voters that believe abortion should be illegal in most cases.

To most people, this outspoken religious group has enough rhetoric to chalk up all advocation against abortion to religion, but evangelical Protestants actually have a rocky history with abortion legislation.

In fact, Morgan Redmon, an Evangelical Protestant, has a different view of the Bible than the current explanation in the media.

“It’s a hard situation for people that are Christian because our backbone is we’re supposed to treat everyone equally. In that sense, no human or child should be cast out or put aside but I think, at the same time, we need to figure out what’s best for the person that is carrying this child, in the sense that they are more important in this situation because they are the ones that are actually living and breathing,” Redmon said.

Unlike Catholics, the religion with the fourth-highest percentage of voters who believe abortion should be illegal, who have consistently advocated against legislation allowing abortion, evangelicals switch back and forth on the issue.

Historically, the evangelical position on abortion has swung based on the public sentiment towards Catholics at the time.

Up until the 1960s, Catholics were seen as disloyal to their countries and racially inferior. Protestant religions tried to distance themselves from Catholicism, resulting in pro and neutral-abortion sentiment since Catholicism was one of the first religions to develop anti-infanticide and anti-abortion laws, separating themselves from early pagan faiths.

“Abortion is not a theological problem,” said Pope Francis VIII. “It is a human problem. It is a medical problem. You kill one person to save another in the best case scenario… It’s against the Hippocratic oaths doctors must take. It is an evil in and of itself.”

Not even when Roe v. Wade was first passed in 1973 did Protestant groups protest. Paul Weyrich and Jerry Falwell, two of the most prominent organizers of the religious right, didn’t use abortion as a platform issue until 1978.

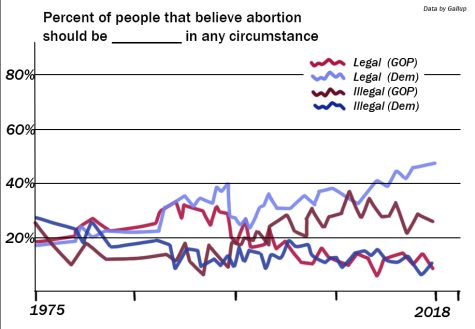

In fact, evangelicals started becoming more conservative around 1980. Yet, according to Gallup, the Republican Party’s sentiment toward abortion didn’t change until the mid-1990s, suggesting that a different platform issue caused this political organization.

By the 1990s, discrimination against Catholics was almost nonexistent, and the Klu Klux Klan had replaced them with a new target: Jewish people. During this time, hate crimes against Jewish people made up between 75% to 85% of all United States hate crimes.

This was the nail in the coffin for pro-abortion evangelicals. Catholicism’s disdain for abortions was now trendy, and Judaism’s ready acceptance was condemned.

All this to say, if abortion was only a small part of the organization of political Protestantism, race was the main uniting force.

“‘I tried everything to get them involved in politics. I tried the abortion issue. I tried the women’s rights issue. I tried pornography. Nothing got their attention — that is the attention of evangelical leaders — until the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) began to pursue the tax exemption of racially segregated schools,’” Randal Balmer, a historian from Dartmouth College, paraphrased of Weyrich.

Segregation — or rather the lack of it — was that issue. In 1954, the Supreme Court mandated the desegregation of public schools through Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, and in 1976 that precedent was also set for private schools with Runyon v. McCrary.

In 1976, the amount of privately schooled children in religious schools was between 90% to 96%. This directly correlates to the shift of churchgoers towards conservatism.

In 1983, the Supreme Court ruled that the IRS was allowed to remove the tax-exempt status from religious private schools that discriminated on the basis of race in Bob Jones University v. United States. The removal of tax exemption for Bob Jones University had initially occurred in 1975, spurring Weyrich into his leadership over the religious right.

Discrimination wasn’t a good look on the national stage, however. Voters were much more likely to vote on abortion, even though voters did not rate it as an important issue in the 1980 presidential election. Former President Ronald Reagan won his presidency in 1980, possibly due to his outspoken opinion on abortion.

At the end of the day, the anti-abortion narrative leads back to race anyway. In a report by the CDC, white women were the least likely racial group to get an abortion. This is correlated to multiple causes, including fewer unintended pregnancy rates. Black women were also almost three times as likely as white women to die in the birthing process, most likely caused by systemic racism in the medical industry. Many of these problems are also caused by black women’s low wages, about 63% of white men’s earnings. Without sufficient funds, people of color are unable to properly care for children, buy birth control for themselves, and pay for decent healthcare.

Race isn’t the only underlying factor of the “religious” right. While evangelicals take the forefront of the political field, many religions disagree with evangelical Protestants on abortion. Judaism, and quite a few protestant religions, support abortion in at least some cases. Other religions, like Buddhism, Islam, and Orthodox Judaism, have not stated any official position, leaving the political choice up to their constituents.

“The big question of what makes the Jewish position very, very different from the Catholic and Evangelical Christian community is that taking the life of a fetus was not considered by any means as murdering a human, meaning that during pregnancy at any stage to birth, the fetus is not considered a full human being,” said Moshe Levin, a retired rabbi.

However, even when religious leaders announce positions, they do not always signify the general beliefs of their congregations. As of 2019, about 29% of religious U.S. adults said that they did not have confidence in their clergy to provide advice on abortion legislation, with another 30% saying that they only had some confidence.

“I think it’s fine to not have a child because it could affect you and the child if you keep it,” Redmon said. “I think in the end, that’s just going to make it a lot worse, and that’s not what God wants you to do, but I think it’s something that you and maybe God have to figure out: Is this a situation that is good or is it a situation that would make me and a child worse?”

In fact, President Joe Biden is a Catholic himself, yet he supports abortion, as shown in his official statement that was released after the Supreme Court’s unofficial ruling. This goes directly against his religion’s stance.

With so many high-ranking politicians having ties to religion, the separation between church and state seems almost impossible, with many Americans now questioning the Supreme Court.

“The religions and their viewpoints should not have a say in legal issues in the United States of any sort because of the separation of church and state, which is actually a fundamental principle of our country and one of the reasons our country has succeeded where it has,” Levin said.

While many people think that religious judges should recuse themselves from cases involving abortion, this isn’t an option, as a legal standard has been set to allow religiously affiliated judges to rule on cases involving abortion.

As of the ruling, the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization would limit abortions to six weeks in Idaho, Texas, and Oklahoma; 15 weeks in Florida and Virginia; 20 weeks in West Virginia; and over 22 weeks in all other states.

“I’m hoping that the outcry against it forces [the Supreme Court] first to withdraw that preliminary ruling, and secondly, to realize that they may have a majority on the court, but they don’t have a majority in the country,” Levin said.