Challenging the boundaries of AI ‘art’ and the human experience

There is a common saying in the art community: “Learn the rules before you break them.”

The first usage of this rule suggested that an artist should learn anatomy, perspective, and other primary artistic skills before they bend those rules and stylize their work.

Today, this phrase applies to more than cartooning: veteran comic artists can use shortcuts for backgrounds like imported 3D models or custom digital brushes to save time.

Art shortcuts extend further than the illustration: to the body and mind of its illustrator. Is it worth it for an artist to dedicate hours to an establishing shot of scenery in their comic if there’s software that can do it for them? How far can a “shortcut” go before the product is no longer the artist’s creation but one of their tools instead, and where does artificial intelligence (AI) sit on that line?

AI art has been a big buzzword in the art community since the pandemic. However, AI image generators like Aaron have existed since the 1970s, according to TechTarget.

AI image generative technology has advanced significantly since Aaron, leading to the widespread usage of new AI software like Midjourney and DALL·E. While Aaron was an experiment, Midjourney is an exploration. According to St-Art, industrialization hit art hard, and designers needed to find ways to make art cheaper and more readily available to the public in the form of advertisements.

Art can be a physical stimulus or a more profound communicative method of sharing the human experience. “Creative works are no longer just read, watched, or listened to. They are often referred to as ‘consumed,’” according to The Harvard Crimson. The public consumes both genres through social media, in-person purchases, or online comic websites.

Art has become a commodity to be bought and sold by large corporations or claimed as non-fungible tokens (NFTs), according to Motiva. Digital art tends to have less value in the eyes of collectors than traditional art, and it’s easy to see it as inferior due to its prevalence.

In a study conducted by SpringerOpen for their cognitive research journal, two pieces of art were labeled as AI-created or human-created, but sometimes the piece labeled as AI was created by a human, and vice versa. They found that whether AI or not, people typically choose the piece labeled human.

AI art has traveled from social media and small projects to professional publishings, like Grubaugh’s Abolition of Man.

It’s unrealistic to assume that, with respect for human artists, people will always hate AI just because it’s AI. Pinterest, a popular destination for uninspired artists, is now flooded with AI-generated images that range from fantasy character concept art to home interiors.

As much as artists believe that humanity will always prefer a bad drawing made by human hands to a good one made by AI, the opposite is already happening.

When oil painter-turned-award-nominated cartoonist Carson Grubaugh submitted a prompt into Midjourney, and the first image it spits out was “stunningly good,” Grubaugh messaged his friend and publisher Michael Robinson.

“’Dude, check this out. We are f***ed,’” Grubaugh said. “He responded, ‘We need to make a comic with this ASAP. Someone else will if we won’t.’”

AIPRM predicts that the first AI-generated movie will come out in 2030, but Grubaugh and Robinson established the comic industry one step ahead when they published the first AI comic in 2022.

Grubaugh knew from Luciano Floridi’s “Philosophy of Information” that to make something out of this market, he needed to be the first and best to do it. The comic needed to have substance.

Grubaugh decided to make a statement and use Midjourney to interpret C.S. Lewis’ essay, The Abolition of Man.

“The essay is a powerful piece of writing that has influenced much of my thinking and art. It argues that mankind has a historical tendency to want to conquer nature — to make our lives easier. Science is entirely about that pursuit,” Grubaugh said.

Grubaugh finds Lewis’ point about blind progress very convincing. In the philosophy of science, blind progress is the idea that scientific progress has no moral framework. In other words, all progress is good progress.

“If we treat progress as blind progress, as science and many social movements do, we are very likely to drive ourselves off a cliff. True progress is towards a goal, and if you realize you aren’t headed towards your goal, turn around,” Grubaugh said.

In the first volume of “The Abolition of Man,” Grubaugh explores the potential results of this blind progress.

“There were four more volumes of the book that explored my own personal ideas about a banal, content apocalypse, in which it is too easy to make new content, so due to option-paralysis, all content becomes basically worthless,” Grubaugh said.

Many artists and art appreciators find refuge because they don’t believe AI will ever be able to replicate the creative process that goes into art.

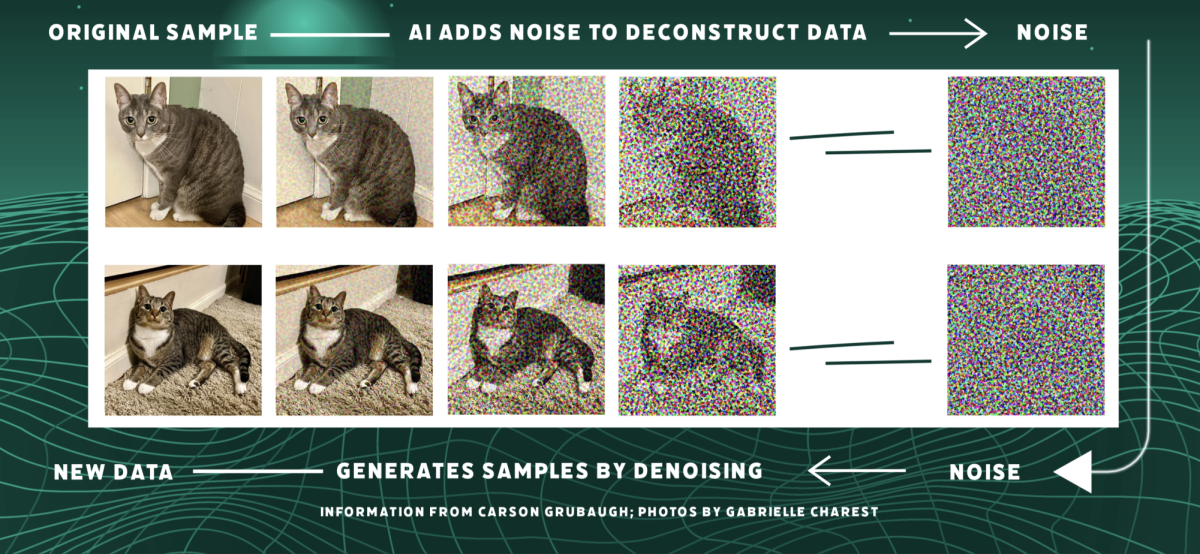

AI may not be able to replicate the human creative process. But it certainly has a process. During the creation of “The Abolition of Man,” Grubaugh experimented with Midjourney to get different results.

“We used Midjourney as stupidly as possible. The less I tried to be good at prompting the AI the easier it was to see how it thought. A good AI artist is, in my opinion, kind of like a bully or a micromanaging boss, forcing the AI into what they want. I found it much more fun to let the AI do whatever it wanted to do,” Grubaugh said.

Grubaugh points out that the results became less original as human biases influenced Midjourney’s data.

“Unfortunately, now that the general public is using the tech we are now teaching it our preferences. The general population is always going to head toward the average, so the images have become sadly more predictable over time and the newer work looks far less creative to me than the stuff we were getting back in 2022,” Grubaugh said.

Art has been with humanity from the dawn of time. The first cave paintings were dated to be over 64,000 years old according to Science. From Neanderthals smearing blood onto stone walls to children scrawling with chalk in the driveway, art has followed humans, and humans have followed art.

So, like carriages came for horses, and cars for those carriages, will human art become a novelty of the past and AI become the precedent?

Most artists don’t think so.

“I think of it like the difference between hearing a musician performing a piece of music versus a computer doing it. Aside from the novelty factor, there is no connection to the computer. It could speed up the music beyond what the musician would be capable of, make no mistakes, play a lot more notes, etc., but would anyone care? I don’t think so,” Granov said.

Since AI art gained popularity, Granov’s opinion has remained constant.

“The same could be said about athletes. Do you care that a car can go faster than Usain Bolt? I don’t. We are dazzled by the new tech, but in the end, it’s just a soulless tool without the connection we feel to the human experience,” Granov said.