“Breathe in…1…2…3…4…Breathe out…4…3…2…1,”

She counts in her head in an effort to meditate. She seeks this out as a possible remedy for the chronic pain in her calf. Just after settling into a meditative state, an invasive itchy feeling appears on her nose. She attempts to refocus on meditation, but her discomfort is overwhelming. She watches her hand approach her face as if she has no control. Her finger scratches her itch, breaking her relaxed state. “Oh well,” she thinks, “at least my nose doesn’t itch anymore.”

Discomfort. It is so much more potent than any promise of long-term benefit. However, for many student-athletes, the search for long-term benefit is hindered by much more than an itch they need to scratch.

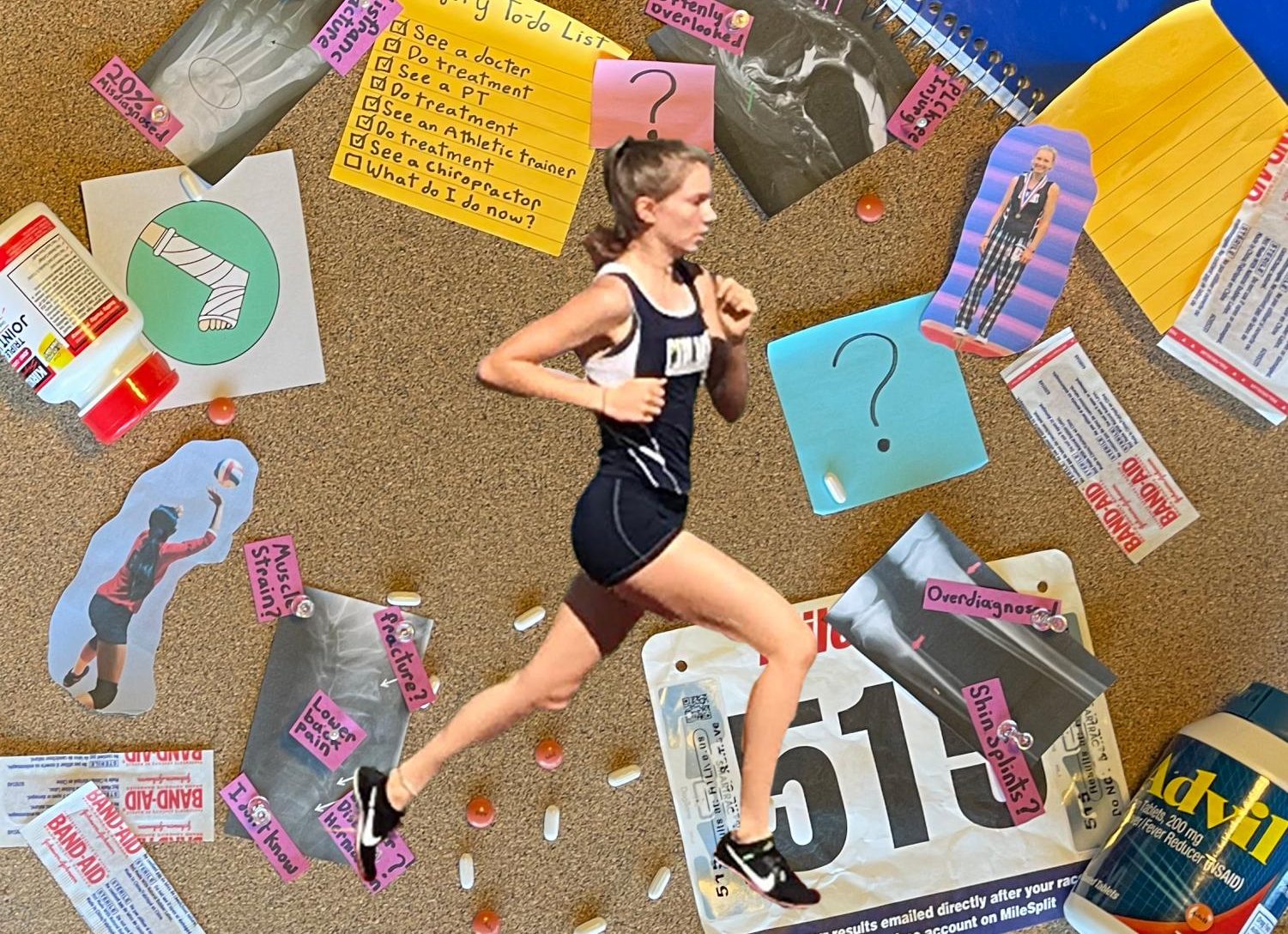

In the U.S., rates of uninformed early sports specialization continue to increase. Simultaneously, the American medical system is not designed to treat chronic sports injuries. This combination resulted in the current system that leaves many injured student-athletes with confusion around treatment, even after seeing their general physician.

One student-athlete who has had a particularly challenging experience with chronic injury treatment is Sabrina Jackson, a cross country runner for the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB).

Jackson, a Carlmont Alumni, was a competitive high school cross country athlete who qualified for the 2018 California state championship in 10th grade. While preparing for cross country in the fall of 2019, Jackson started to have a weird feeling in her foot.

“I felt [pain in my foot] a little bit so I took a couple of days off of running and it was gone. I started running again. Two weeks later, it came back and after running through it a little longer I saw a general physician,” Jackson said.

Seeing a general physician was not the end of Jackson’s injury. After two years of seeing over 10 medical professionals and having two cast sessions, three MRIs, a couple of X-Rays, and three different diagnoses, Jackson still has a foot injury.

“I still have my injury to an extent. I had another MRI in [October of 2021] actually and it showed that the inflammation is almost gone, but that some of it is still there,” Jackson said.

Confusion plagued Jackson at every stage of her injury experience. Her general physician initially misdiagnosed her with a foot sprain. Later she was misdiagnosed again with plantar fasciitis, resulting in her first cast session. It was an MRI that revealed Jackson’s actual injury, a bone bruise in her foot, a diagnosis resulting in a second cast session. All three of these injuries have different treatments, and the confusion around them slowed Jackson’s recovery.

“For the first year and a half with my injury, I did absolutely no activity. After both of my cast sessions, my foot and whole right leg were so weak that I couldn’t move them. I couldn’t even drive for five months after I got my second cast off,” Jackson said.

According to Jasyn Chidester, a certified athletic trainer at Stanford’s Lucile Packard Children’s Health, rest is not always the appropriate response to injury.

“The initial idea of rest is best is based on an outdated principle from ages ago where [doctors say]: ‘you are going to rest for weeks on end and see how you feel.’ That actually can be detrimental to your health because you’re not getting necessary physical activity,” Chidester said.

Unfortunately, a number of doctors still commonly defer to rest and cast treatments for injuries, even if it is not the best approach. Lucia Herrera-Set, a sophomore at Carlmont and gymnast, had an experience with confusion and a cast for her chronic ankle injury.

“[My doctors recommended a cast because] they didn’t know what to do. They said that I could take a break for a little while or put my ankle in a cast. My response was that if it’s going to heal faster, then I’ll wear a cast,” Herrera-Set said.

Herrera-Set’s confusion about her injury started like Jackson’s, with the diagnosis.

“My ankle has hurt for a long time, but it started hurting more in 2020 so I decided to go to the doctor to make sure nothing was wrong before the season. I got an X-ray and they didn’t know what it was because I have an extra bone in my foot and the X-ray showed that it was either broken in half all the way or that I have two extra bones. I never really knew what happened,” Herrera-Set said.

Over a year after wearing a cast, Herrera-Set said that it may have resulted in dissipating her pain, but that “overall, the cast didn’t really do what it was supposed to do because my ankle still hurts.”

Herrera-Set continues to compete as a gymnast with her ankle injury. She has been able to manage her pain since she got her cast off, but it never fully has healed.

Another student-athlete who has experience with having unanswered questions is Sofia Cueva, a sophomore at Carlmont who plays club volleyball. She injured the lower part of both of her legs at volleyball practice.

“In early October of 2020, I started doing box jumps 50 times a practice, three times a week. I had never done them before so I landed on the floor wrong, and it triggered pain in both of my legs around the tibia. So then I took a week off from practice, and it stopped hurting, but when I went back to practice, it came right back,” Cueva said.

Cueva developed liquid build-up in her calf area by doing box jumps improperly for months, information that was unbeknownst to her for the first few weeks of dealing with her injury. Instead, Cueva began treatment for the incorrect area after listening to advice from doctors.

“I started seeing the doctor in October of 2020. For the first few weeks, they told me several times to keep on icing it and stretching it, but they were telling me to stretch the wrong part of my leg,” Cueva said.

According to Adam Dekeyrel of Dekeyrel Chiropractic, tibial injuries like Cueva’s can be challenging to diagnose because a lot is going on in that area that is difficult to see.

“It could be the Achilles tendon which is usually triggered when you hurt your lower leg with Box Jumps. And maybe there is some slight tearing or some inflammation there, or it could have even torn away from the bone a slight amount, but it is not that noticeable on X-ray,” Dekeyrel said.

Cueva’s doctor diagnosed her injury after giving her an X-ray and an MRI.

“[My doctor] diagnosed me with a stress reaction and told me that I would be able to go back [to volleyball practice] in two months after doing physical therapy,” Cueva said.

Cueva is not alone in seeking further treatment for a stress reaction. According to a study by NCBI, stress reactions account for 20% of all injuries treated in sports medicine clinics. In Cuevas’s case, receiving adequate treatment was difficult.

“When I started [physical therapy], we would only do stretching exercises. And then [my injury] would progress. I was able to start running again. But when I started running again, that’s when it would start hurting again. And that happened over and over again. After going [to physical therapy] for two months starting in April, every two months, they would tell me I was clear. I would feel pain again, and I had to keep going back,” Cueva said.

At times, physical therapy, even when done correctly, is not always beneficial to a patient. Dekeyrel identified several reasons for this.

“Physical therapy is mostly stretches and exercises to strengthen and heal tissue. It blocks the pain at best, but it does not do any healing at all. Usually, people who do physical therapy will strengthen and stretch their injury and then stop after [it starts to feel better in] maybe two months or so. Often after that patients don’t see any extra success,” Dekeyrel said.

Chidester further explained why success in treatment plateaus, adding that patients often do not follow through and complete the whole healing process.

“The reason why [some athletes] are not ready to come back is because they didn’t advance in their exercises or do the proper route of care to help speed up the healing process in physical therapy,” Chidester said.

Cueva’s case, however, was not due to a lack of following through. After the prolonged nature of her injury prompted curiosity from her general physician in Cueva’s treatment, she realized her physical therapist may have given her incorrect exercises that would do little to alleviate her pain.

“I went to the doctor’s office, and the doctor asked me what exercises I’ve been doing. I told her, and then she said, ‘Well, I’m not really sure if those exercises will help your leg, those help more for strengthening your glutes.’ I told her that the physical therapist said that if I strengthened my glutes, somehow, it would help with my tibia,” Cueva said. “She said that that wasn’t factual, but she was gonna email my physical therapist and ask them what exercises they have been giving me, and she will clarify with them and who was right. She hasn’t gotten back to me.”

Knowing what treatment is appropriate for chronic injuries, especially ones as niche as Hererra-Set’s or Cueva’s, has a lot to do with the specific medical professional one sees.

There are many people a student-athlete might go to when they experience a chronic injury. Private businesses and centralized hospital care make up the American sports medicine system. The latter is most patients’ starting point. After seeing a general physician as the first step, patients with chronic injuries are typically told to rest for a few weeks. If resting does not fix the injury, general physicians’ next step is to refer the patient to physical therapy. If patients have not recovered at this point, many move on to less centralized care like sports medicine doctors. When all else fails, patients may see a chiropractor or the certified athletic trainer (ATC) at their school.

Many injured students go through seeing every type of injury-focused medical professional. The result is often confusion that prompts questions in which finding the correct answers is difficult.

“The problem is that there’s too much information out there on platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and everything else. There’s so much that people get overwhelmed and they jump from program to program. So I think that it’s really hard to find somebody who knows what they’re doing. And it’s really hard for these year-round athletes who have no offseason,” Dekeyrel said

During her long and confusing series of diagnoses, Jackson used every resource available to her in hopes of understanding the information that would fix her.

“My mom and I were super into searching stuff up, even after it was diagnosed, I felt like my doctor wasn’t giving me enough guidance for what I should do from there. So we would look up things like ‘how to treat a bone bruise’ and everything online. Even now, since my injury relapsed, my mom and I talk about our theories for what is happening in my foot. I do so much research,” Jackson said.

The student-athletes with confusing medical experiences in a transitioning age to super-athlete have a takeaway from their experience that acknowledges both the humanity of doctors and the importance of self-advocacy.

“I know my body best, your doctor or doctors don’t know your body or how you are feeling best and so when one of my doctors said: ‘Oh, it’s plantar fasciitis.’ I thought: ‘I’ve had plantar fasciitis before and I know that’s not what it is.’ But we just kind of do what our doctor tells us to do because we like to think that doctors know everything, but they don’t,” Jackson said.