A Unique Childhood

Noah Cartan was predicted not to live past three months.

At the end of November 2023, he celebrated his 28th birthday.

Noah was born suddenly four weeks before his due date, leading to an emergency C-section. In the process of saving his life, his cervical spine fractured, resulting in permanent paralysis. He was soon diagnosed with cerebral palsy, which limits his speaking abilities, forcing him to rely on sign language and iPad technology for his receptive language skills.

Growing up with a developmental disability changed Noah’s reality. A milestone birthday has meant something different for Noah and his family. It isn’t just another year older; it means another year alive.

“At one point, we just decided we weren’t going to take these age predictions into account anymore,” said Heidi Cartan, Noah’s mom.

Noah’s parents worked hard to make his childhood meaningful, but his diagnosis led him to a different reality.

“When he was a kid, he was always in a special ed classroom, and he had quite a few surgeries, so his childhood didn’t look like anything we expected,” Heidi said.

Heidi and her husband continued to look for ways to make his life more meaningful and fun.

By his early 20s, Noah had become comfortable with his routine. His day-to-day life involved interactive programs such as drama class, horseback riding therapy, tending to crops, and planting seeds, but even so, opportunities outside of his home were limited.

According to a Forbes article, the few jobs that are available for the disabled population will never meet the high expenses that come with self-sufficiency because so much is devoted to medicare requirements and the necessary healthcare. Due to this reality, the disabled population lives in a never-ending cycle, dependent on caregivers for support without the opportunity to live independently.

Overlooked by perception

Young adults across the country look forward to the day when they can move out and live Independently, but for Noah, living on his own and obtaining a job was never an option, and this fact scared Heidi and many other families like hers.

Dr. Lawrence Fung is the director of the Stanford Neurodiversity Project. One of the many problems his team approaches is the lack of employment opportunities for the neurodiverse community.

Due to Noah’s paralysis and limited receptive language skills, workplaces were never open to him. Still, even for those without physical disabilities or language impediments, there continues to be a lack of acceptance.

“The physical world is not set up for people who need to do their job from a seated position,” Heidi said.

Noah is in his wheelchair at all times, so his abilities restrict him in many aspects, but this doesn’t mean he can’t work when his environment is adapted.

“When I tell people that Noah helps sow thousands of seeds a year on the farm to grow the crops that we grow, they’re kind of astounded; they can’t believe that he can do it,” Heidi said.

Workplaces often overlook the benefits of diversity within the workplace. This lack of acceptance has resulted in a 40% unemployment rate for neurodiverse people in the country, which is the highest unemployment rate compared to any other group in the country. Many employers are hesitant to hire from this group, fearing it will be too much work or negatively affect their workplace, which concerns parents.

“Oftentimes, people on the spectrum don’t have a typical way of presenting themselves,” Fung said.

Fung often deals with autistic patients on the spectrum, and according to his data, the neurodiverse community has the same abilities as a neurotypical person. According to Fung, 80% of the autistic community is unemployed, but only 40% have intellectual disabilities, which means that the majority have strong cognitive functions, a clear indicator of their abilities. As a result of this data, the low employment rate is due to social interaction, not proficiency in the workplace.

“Social interactions are intrinsically part of the evaluation for the positions employers want to fill, so often they will write people off very easily in the first couple of minutes, just by first impressions,” Fung said.

This automatic disqualification limits the neurodiverse community significantly because they don’t have an opportunity to demonstrate their skills and abilities when approached in a neurotypical manner.

“People on the autism spectrum tend not to present themselves in a way that would get people to have a positive impression right away, even when they are highly competent,” Fung said.

Neurodiverse people are hyper-aware of their abilities, so often when reading a job description, they don’t even apply because they perceive every logistic on the job application as a requirement to fulfill and fear not being able to do so.

Searching for a solution, the Stanford Neurodiversity Project operates to assist young people in navigating a life with neurodiversity, particularly young adults seeking education or job opportunities, along with advising employers and coaches on how to best interact with the neurodiverse community.

“What we encourage employers to do is find ways to eliminate situations in which the candidates cannot function because they are too anxious,” Fung said.”One way of doing it is to allow the candidates to receive questions beforehand.”

Small steps go a long way for the neurodiverse community and help to eliminate the anxiety that comes from interviews and interactions with strangers, which is the purpose of Fung’s program. Fung uses a string-based model to revert the outlook of the neurodiverse community.

“Society is focusing on a deficit-based model, so when someone has a diagnosis of autism, they think everything is all bad when in fact there is a lot of good that can be associated with this like someone that can be very interested in a particular topic,” Fung said.

With this new outlook, Fung hopes to make all aspects of society more accessible for the neurodiverse community with the help of new programs and by educating people on the importance of this accessibility.

“There is an alternate way of thinking about a neurodiverse condition, and when we can make the workplace more neurodiversity friendly, then there are more opportunities for them,” Fung said.

Paving the future

The potential for job opportunities has expanded, led by industry pioneers and workplace leaders willing to adapt their work environment to provide safe and comfortable spaces for those with neurodiversity. Rene Ho is one of the many employers who has been a leader in expanding perspectives in high-end workplaces.

Taking a break from the corporate world, Ho was an instructor at Expandability’s Autism Advantage program, where he worked with young adults with autism in their mid-20s to 30s to prepare them for the job market.

“We train through creative project work and introduce them to employers, along with helping them harness resume and interviewing skills,” Ho said.

Ho returned to the corporate world a year later, but his perspective had shifted. Entering a new job as CFO of Taulia, Ho brought along three potential candidates from Expandability’s Autism Advantage program, but the hiring process was not easy.

“I’ve found that members of the neurodiverse community are extremely methodic and have anxiety with strangers,” Ho said. “The interviews were very long and challenging.”

Ho acknowledges that working with the neurodiverse community is unlike working with his other colleagues, but this doesn’t stop him from collaborating and working to understand and adapt to the needs of this community.

Similarly, Heidi is passionate about collaborating with people with or without disabilities.

“We talked about people with and without disabilities, working our land together. And we try to be as barrier-free as possible,” Heidi said.

Ho, like Heidi, encourages others involved in the hiring process to consider the benefits of working with the neurodiverse community and embrace the diversity and challenges that may occur, but prejudice often interferes with acceptance.

“I think the biggest barrier for Noah has been other people’s attitudes and expectations about him,” Heidi said.

According to Ho, the key to understanding this population is treating them like any other individual or human being.

“I think human nature tends to reject people that are different and not embrace them,” Ho said. “It comes from the heart to be empathetic, sympathetic, and embrace the neuro-diverse folks.”

The “Diversity and Inclusion Revolution” supports the idea that people are most likely to approach a business that shows diversity because it produces more engagement with people.

Ho has worked with his two neurodiverse employees for over three years, and seeing their growth and development has inspired him to continue this initiative.

“When I started working with this population, I thought I would be helping them, but I didn’t realize how much they would be helping me. We’re very grateful to them for making unique contributions to the company,” Ho said.

Creating a better reality

Although Noah’s age was a sign of hope for the Cartan family, anxiety and fear crept in for Heidi as she considered her son’s future. Heidi didn’t want to face the reality that many parents are slammed with when they reach the age at which they are unable to care for their child.

“I realized that the government is not building housing for our kids, so what’s going to happen when we can’t take care of them anymore?” Heidi said.

With this thought swirling around in her head, Heidi joined a local community trip to Seattle, Washington, but she never expected to be at the right place at the right time. Embarking on a service project, the group visited a L’arche community.

“The L’arche communities in Washington state are communities where people with and without intellectual disabilities live together,” Heidi said.

Heidi Cartan had heard about programs like this, but seeing it in person inspired her like never before, especially when she noticed the inaccessible pathways.

The idea later came to her on a road trip to Tacoma, Washington during the community trip. Heidi opened the door to a 15-acre farm filled with young adults in a beautiful outdoor setting.

“That’s where I met people who were just like Noah, only older, and they were living very happy, fulfilled lives,” Heidi said.

Heidi had a new initiative, determined to ensure a secure future for her son.

“I came home and told my husband, this is what we got to do,” Heidi said.

This new initiative sprouted into action as Heidi involved other parents in a plan to buy and transform a farm.

“Many people had the same worries we did, which probably shouldn’t have come as a surprise to me, but three months later, we probably had 50 families gathered in a room,” Heidi said.

Heidi never considered herself an expert in agriculture, with limited gardening experience and knowledge about how to develop housing. But she did have a drive and perseverance to ensure the security of her son’s life.

“I thought about what would make a meaningful life for Noah and how he would receive care if he outlived his parents,” Heidi said.

On a worried-filled night like many before about Noah’s future, Heidi was scrolling through Zillow when she found what would soon be Common Roots Farm.

11 families came together in 2015 to put together their resources and take the initiative to buy the farm.

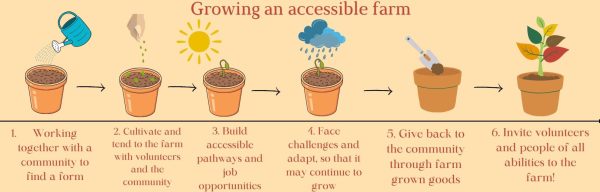

Each day, volunteers and young adults with disabilities work together on new projects and initiatives to keep the farm going.

Each year has been a milestone on the farm. The community has the opportunity to enjoy farm-grown and handmade goods.

However, the most significant development that has continued to blossom on the farm is the established housing. After witnessing the L’arche communities, Heidi knew the farm’s purpose was to be a home where young adults with neurodiversity and disabilities could rely on each other.

“The parents here would tell you that having their child live independently and know that they’re set for the future has truly changed the parents’ lives,” Heidi said.

Six homes have been built over the last eight years, and as of two years ago, 18 adults with disabilities from the age of 23 to 42 moved in and began to live with each other and rely on one another with the help of caregivers on the farm.

“We’ve had a lot of barriers and obstacles, and it’s not perfect, but it’s working for most residents, and their quality of life is good and getting better all the time,” Heidi said.

Of the 18 young adults living on the farm, each has a diverse but fulfilling routine and many programs and activities they look forward to participating in.

“The rest of the community values and understands growing good food and beautiful flowers and donating food to local food banks, which is what we do here on the farm,” Heidi said.

“So here, people with disabilities are helping to feed their community.”

Outside of farm activities, many of the young adults spend their time taking walks to downtown Santa Cruz and onto the boardwalk. Others have pursued paralympic training and competitions, and many enjoy therapeutic horseback riding.

Noah, in particular, has opted for his drama club as his favorite way to socialize with his friends.

The farm has undoubtedly changed the lives of these families.

“Parents are grateful to have some peace of mind that their child’s future is not just hanging in the balance in the big unknown, but that they’re building relationships, friendships, and they have a neighborhood now that they can feel secure in,” Heidi said.

Heidi challenges people to look past preconceived ideas about the abilities of the neurodiverse and disabled folks as the community has done so through their involvement in the farm.

“Neurodiverse people can think out of the box; their way of thinking is so different that it can be so valuable,” Fung said.

The farm continues to blossom and invites anyone into its warm, diverse environment that pushes past institutionalized boundaries.

“It’s like magic when you allow them to integrate and be included in a wider endeavor. That’s the best way to break down those barriers,” Heidi said.