Opinion: English spelling needs to be changed

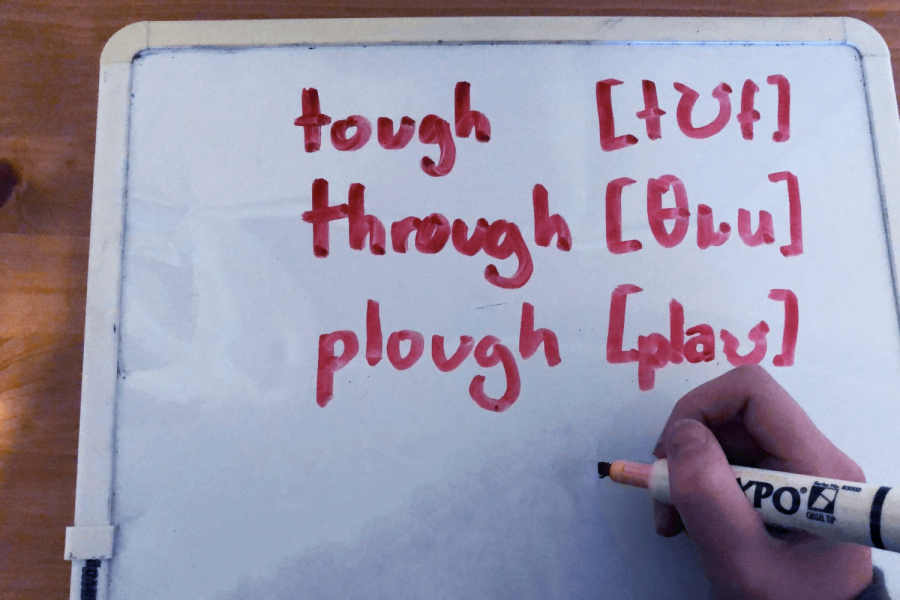

Spelling in English is notoriously unpredictable, with words such as through, thorough, tough, and plough having the same series of letters, yet making completely different sounds.

Anita Beroza, Staff Writer

November 3, 2021

English spelling sucks.

It’s true— it’s the complaint of every student who lost points on their essay due to typos, publishing proofreaders, newsroom editors, and anyone learning English as a second language. Why should “should,” “sugar,” “titration,” “schwa,” and “chauffeur” all spell the same exact sound five different ways? Why can “ough” have a unique sound in “plough,” “cough,” “tough,” “through,” and “thorough?” Currently, English has such a disorganized canon of letter arrangement that America puts middle schoolers doing their best to make sense of this bastardized tongue on ESPN primetime once per year.

But never fear, English orthography haters! I have a solution for you. Granted, it only applies to American English, but I think roughly a third of a continent should be enough for a first stab at this.

Credit where credit is due: I am certainly not the first person to think of modifying English spelling. Such ideas have been put forth in the past– the atrocious spelling of ptarmigan is an unfortunate example of a successful modification. Many a historical celebrity has proposed their own reform, including figures such as Benjamin Franklin and Noah Webster. Many of the distinct markings of the American dialect are due to Webster’s efforts.

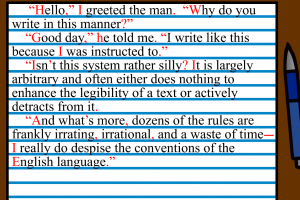

However, these all too often either fall short of what I would argue to be the ultimate goal (fully phonetic spelling) or do achieve this goal but create their own letters in a nonsensical, frankly irritating manner. Plus, the supreme benefit of my orthographic reforms is that they can still be sung in an alphabet song. What more could one want?

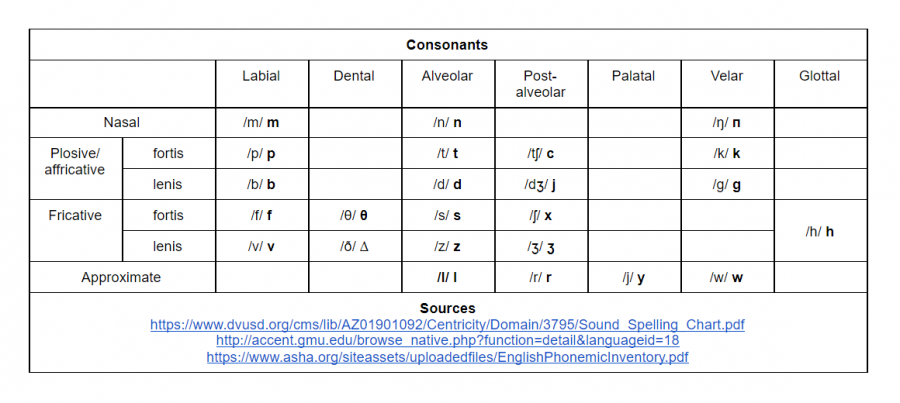

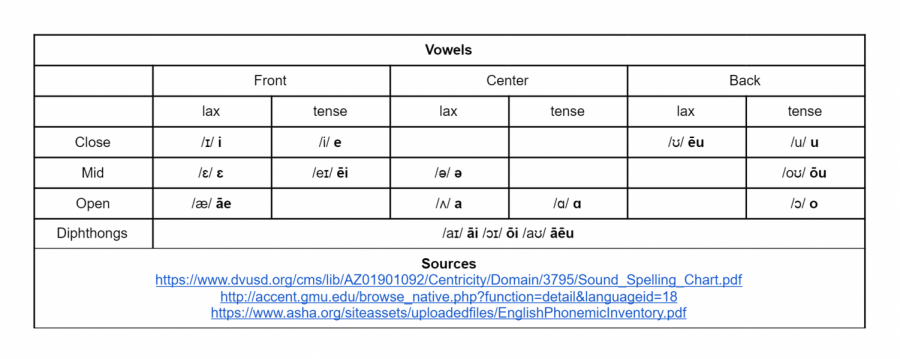

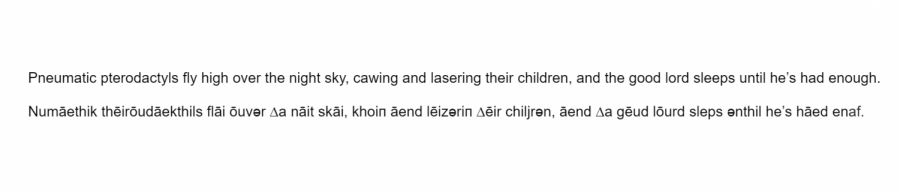

Observe my magnum opus. The letters in between slash marks are the characters used in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to represent the sounds in English, and the un-slashed letters nearby are the characters my spelling reform would use.

Diphthongs are indicated with a macron (line) over all but the last vowels involved in its spelling. All consonants have unique sounds, and, except for the diphthongs, distinguished with their diacritics, so are all vowels.

Despite its sheer, earth-shattering genius, this system is, more than likely, not without its critics.

“Using pe for the ng sound doesn’t make linguistic sense! Pe is the Cyrillic letter for the p sound; it shouldn’t represent ng! It’s from the Greek letter pi, for goodness’ sake!” whine pedantic losers who have never heard of aesthetics.

I spit on your silly etymological history. Pe looks like n, and, to English speakers, the ng sound made at the end of words like “ring,” “king,” and “writing” is made with the Latin letters n and g, and is a nasal consonant just like n. Thus, the character should be closely associated visually with an n. Design trumps all.

“Why can’t you just use the IPA?” the alien breeds of hardcore language learning hobbyists, linguists, professional singers, phoneticists, accent tutors, and English teachers might ask.

I sympathize with this request; I really do. I love the IPA. However, many of its letters are useless for the English language (imagine trying to sing an alphabet song with dozens of consonants and vowels that don’t even get used!). The characters are often unfamiliar and look deeply out of place with an otherwise Latin script.

Obviously, the only solution to the dilemma is a complete overhaul of the American writing system in the manner presented with my lovely tables.