Diving to the floor, tucking into a tight ball, and squeezing her eyes shut, the trembling stopped. Peering out the window, she saw the thick black clouds rise towards the heavens. The restaurant with the Americans had been bombed.

Caroline Hao Hoan Do was nine years old when she first experienced the reality of the Vietnamese war.

Over four decades ago, millions of people sat on the edge of catastrophe. As South Vietnam collapsed, the future of its people laid in jeopardy. Fearing the violence and turmoil that would follow, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese fled their homeland in search of safety, many of whom sought refuge in the United States. Congress wanted to shut the door on them, but President Gerald Ford convinced the country to be on his side.

“We’re a country built by immigrants from all areas of the world, and we’ve always been a very humanitarian nation,” Ford said in 1975.

America, under Ford, rescued nearly 200,000 Vietnamese refugees. As one such refugee, Do will never forget what the U.S. did for her.

And how could she?

War leaves many scars on its victims, and Do was no exception.

Back in Vietnam, Do lived a relatively comfortable life as the youngest of four sisters and three brothers. Her mother ran a jewelry shop in the central shopping district while her father was a successful real estate developer who often traveled internationally. Living in Saigon, the devastation of the war rarely reached them.

South Vietnam’s capital was well protected by both American and South Vietnamese soldiers. At least, it was, until the U.S. withdrew.

Anti-war movements, coupled with the lack of military success, lead to the beginning of the U.S. withdrawal.

By March 1973, the last U.S. troops returned home. South Vietnam was left to fend for itself with limited aid from the U.S. For the Americans, the war was over — but in Vietnam, the North Vietnamese, backed by China and the Soviet Union, continued their campaign into the South.

Just over two years later, on April 30, Saigon was in the hands of the North Vietnamese. Fourteen-year-old Do had escaped only a few days earlier.

Even before South Vietnam fell to the Communists, leaving the country was a perilous matter. It was dangerous to reach out for help. If the government discovered people attempting to escape, they would severely punish them. Likewise, boys above the age of 10 were not allowed to leave the country to prevent them from evading the military draft.

Luckily, Do’s father rented out rooms for ambassadors and journalists, many of whom were Americans. Drawing on those connections, Do’s mother managed to find help. On April 23, Do had to leave everything behind.

“Okay, just bring a bag. That’s it. And you need to leave right away,” Do recalled an American soldier saying to her mother.

Do boarded the C 130 cargo plane, with hundreds of fellow refugees covering every square inch of ground. The aircraft took off in the dead of night, avoiding detection from the North Vietnamese.

Without a heating system, Do was left in frigid temperatures for hours until she reached the U.S. base in Guam, more than 2000 miles east of Vietnam. There, troops and volunteers welcomed them. Do still remembers her first meal there: a steaming hot pea soup.

With the help of the Americans, she was able to reach safety, and weeks later settled down in Washington, D.C.

Two of her uncles weren’t so fortunate; they were left behind. One was a military doctor, the other was a policeman and they were both sent to labor camps. The policeman was a prisoner for nearly 10 years subject to abuse, torture, and intense physical labor.

“The Communists work you until you get sick or you die. They don’t care,” Do said.

Back in Washington D.C., Do was sent straight into the ninth grade. While she had to overcome a significant language barrier, she was able to make friends and settle in by her second semester.

With government-granted financial aid, specific to refugees, Do was also able to attend college. At the University of Maryland, she earned a bachelor’s degree in music, soon finding her passion as a piano instructor. Do has been teaching piano for 33 years and has taught over a hundred students, ages ranging from 5 to 60 years old.

“I grew up here, so I had no problem. Even my brother and sister had no problem with finding a job because we all got to go to college and get a degree,” Do said.

Currently, Do lives in the Bay Area as a semi-retiree. She often meets up with friends and family, including her best friend from first grade, who reunited with her in the U.S. Unwaveringly grateful towards America, she believes that the government gave her and the Vietnamese community a second chance.

Despite Do’s happy ending, many believe that even today, 45 years after the Vietnam War, America has failed to live up to their responsibility of aiding refugees.

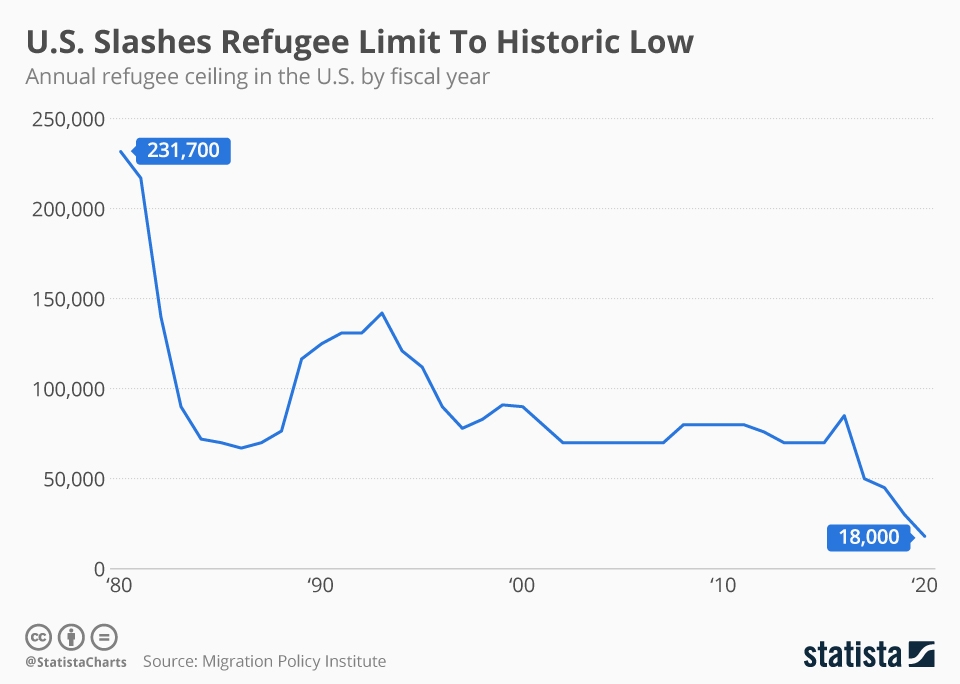

There were 7,000 people in the 2018 migrant caravan, which was enough to be called a “national emergency;” however, the caravan included less than 0.1% of the refugee population. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the refugee count increased to a record high of 78.8 million or approximately one refugee per 100 people. Regardless of this emergency, the United States continues to build walls and block out refugees.

“What I won’t do is take in 200,000 Syrians who could be ISIS,” President Donald Trump said during “Face the Nation” on CBS.

In America’s place, other countries are forced to accept the brunt of those who are displaced. Countries such as Turkey, Pakistan, Uganda, are all hosting over a million refugees. The problems are ever-growing, while the solutions seem scarce.

However, David Miliband, the CEO of the International Rescue Committee (IRC), believes the issue is “manageable, not unsolvable.” He offered four solutions: let the refugees work, educate their children, provide economic support for individuals, or give refugees a new country to live in, especially in western countries.

Indeed, the U.S. alone cannot single-handedly solve this refugee crisis but this doesn’t mean America should ignore it. They could start small, setting the trend for other countries to follow. If nobody takes the first step towards a solution, the issue will escalate and become increasingly harder to solve, as does any problem.

“The numbers are relatively small; hundreds of thousands [of refugees], not millions, but the symbolism is huge. Now is not the time to be banning refugees. It is a time to be embracing people who are victims of terror,” Miliband said in a TED talk.

Refugees leave their home for survival. When no options are presented to them, they are forced to take risks to reach safer areas. Resettling hundreds of thousands of refugees across America is a big task. In the short term, competition for jobs may be harder, but as time passes, society can begin to adapt.

Accepting refugees is not only a question about practicality — it’s a test of humanity. Is it right to send families back to where they came from, be it war, gang violence, or poverty? Is it right to stay idle while people search for a safe place?

“The refugee crisis questions the basis of our humanity. It’s a test of us in the western world, of who we are and what we stand for. It’s a test of our character, not just our policies,” Miliband said.

The United States has been a role model country. Despite strong opposition, President Ford stayed with his morals and rescued those in need. Now, 45 years since then, the once vulnerable refugees have become an appreciative and vital part of American society.

“We are lucky to be able to live in this country. This country has freedom of speech and freedom of religion. It’s a blessing,” Do said.