The moment someone sets foot in a prison is the moment that person stops living.

“In prison, the environment really makes everyone feel like they can only exist; living doesn’t seem like an option anymore,” said Frederick Griffin.

Griffin was 16 years old when he was charged with multiple offenses, including gun charges and gang enhancement. At 17, he entered the California Institution for Men in Chino, California, and immediately, he could tell a facility like this—with its soiled floors, cramped cells, and windowless walls—was designed for containment, not rehabilitation.

However, physical design was not the only unwelcoming characteristic of this prison.

“At Chino, there were these unspoken rules and expectations, ones that exist just to fuel the masculine behavior of prison culture,” Griffin said. “If you broke them, it could get you really hurt, maybe even killed.”

A few of these “unspoken rules” included no shouting, no running, no dancing, no laughing, and no crying.

So when Griffin heard about a dance class being held at the prison, he struggled to believe the news.

This dance class was a program called Embodied Narrative Healing, which the prison created at the request of two other inmates. Griffin decided to give the class a shot, not knowing just how much this program would change his life.

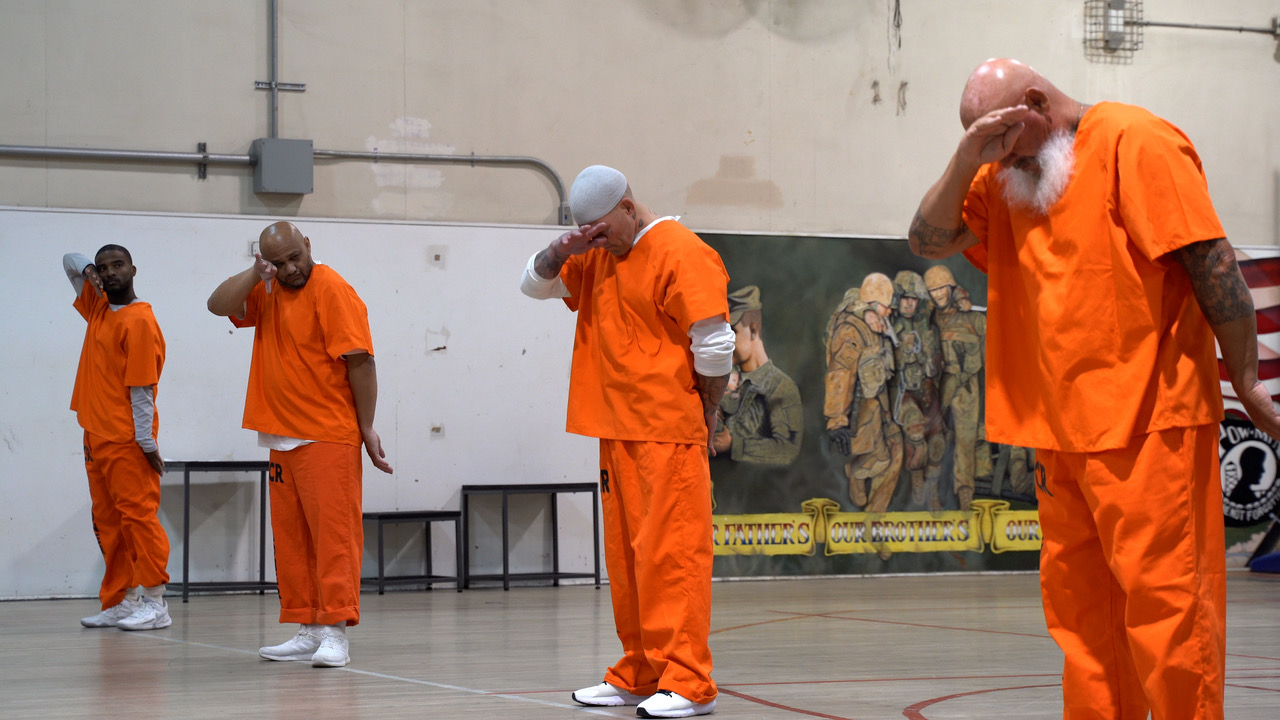

Set in a small, empty space between the bathroom and the showers, the class was taught by Dimitri Chamblas, a professional dancer and the dean of the school of dance at the California Institute of the Arts.

“He hugged me when I first met him, and I could just see there was no distinction; he did not see an inmate when he stepped into the prison. He only saw a human being,” Griffin said.

Chamblas would lead the group through some basic movements including swaying side to side or extending their arms in different directions.

“He tried to teach us some ballet moves, even,” Griffin said. “He said jokingly once that if we were advanced enough, he’d show us how to do this one big leap called a grande jeté. We never got there, but still, his class was the real deal.”

However, what stood out to all the participants was the amount of partner work Chamblas would include in the class.

I felt peace. I felt fear. I felt anxiety at times, but I felt alive.

— Frederick Griffin

“There were some moments where we were full-on leaning on each other. We were all shocked because this level of touch is extremely rare,” Griffin said. “In prison, most of the time, if you ever come in contact with another human being, it’s either because you’re being searched or you’re in some kind of physical altercation.”

In a place where a playful sway in the hips or a rhythmic groove in the shoulder once felt forbidden, Griffin began to find freedom in movement, and it was hard to miss the positive influence it had on himself as well.

“I actually felt good. I was in prison, laughing like a child. I was able to shake and laugh and yell in prison. It was very, very different for me,” Griffin said. “I felt peace. I felt fear. I felt anxiety at times, but I felt alive.”

Along with Embodied Narrative Healing, Griffin also participated in a writing program called Words Uncaged, which was created by Bidhan Chandra Roy.

Roy is an English Professor at California State University, Los Angeles, who has been so moved by inmates’ stories that he has made it his mission to offer them the spaces and services they need to get back into the world.

One day, during Roy’s classes, Griffin took the time to write a letter from the perspective of his body, inspired by the movement he was doing with Chamblas and the growth he was seeing in himself.

In the letter, Griffin touches on the shame and lack of appreciation he had for his body due to all the trauma he suffered: a toxic household, a father who had been a gang member, and sexual abuse beginning when he was six.

Although the contents of the letter sound bleak, this written work represents the transformation Griffin had undergone as a result of participating in the two art programs.

“From dancing and writing and just reflecting on myself more, I realized that what I gained from this group was the ability to get back in touch with my body and to realize I am human too, and I am just as capable of loving and being loved as everyone else,” Griffin said.

Serving as spaces for recovery, correctional facilities should offer rehabilitation.

Although the staggering number of people in prisons and rising recidivism rates indicate these facilities are not fulfilling that responsibility, a number of passionate organizations, educators, and other like-minded individuals—including Roy and Chamblas—have put a spotlight on these issues and cued the nationwide journey towards reformed correctional facilities, searching for, testing, and implementing a variety of programs in order to enable those who enter their facilities to develop positive attitudes and life-effectiveness skills.

After their determined studies, it has become clear that instruction in arts is a step, or perhaps a grande jeté, in the right direction.

A reformed vision: Prioritizing rehabilitation over punishment

Programs like Embodied Narrative Healing and Words Uncaged would not be in such urgent demand if it weren’t for the fatal flaw of most prisons: they prioritize punishment over rehabilitation.

Currently, the United States holds 25% of the world’s prison population. With more than 10.35 million people incarcerated in the world, that means the U.S. has more than 2.5 million people in its prisons.

In the past 40 years, the U.S. prison population has increased by 500%. This dramatic increase can be directly tied to law and policy changes occurring over the last few decades.

For instance, the 1994 Crime Bill, a federal crime bill, created harsh new criminal sentences and incentivized states to develop policies that bred bloated prisons.

Under this bill, a person who sold five grams of cocaine received a five-year minimum sentence.

With minor crimes like these bringing down such harsh punishments, along with funding encouraging prisons to increase arrests and prosecutions, people began to view the 1994 Crime Bill as a law that fueled mass incarceration.

As a result of laws like the 1994 Crime Bill, mass incarceration has become a serious issue in the U.S., and it has also caused prisons to become more punitive.

The increased commonality of incarceration led society to respond to crimes by resorting to the criminal justice system, charging offenders with severe sentences and building more prisons to contain the expanding incarcerated population instead of choosing to reduce the crime rate through consistent investments in instructional programs or improved prison conditions, both of which would more directly solve the issue of the U.S.’s rising incarceration rates.

“There’s a kind of fundamental philosophical problem from which problems like mass incarceration and recidivism stem, and that is the disregard we have towards preparing inmates to be our neighbors,” Roy said. “If we shift our mindset and start working towards providing successful reentry, then it becomes clear the current system we have of warehousing and only punishing people is ridiculous.”

When prisoners are released, what kind of neighbor does society want them to be?

— Bidhan Chandra Roy

Noticing the severe impact of the U.S.’s flawed prison system, researchers, educators, and others have initiated many efforts with hopes of transforming the nation’s correctional facilities into places that can lower incarceration rates by punishing less and rehabilitating more.

In 2022, Carlos Villapudua of Stockton introduced a bill, AB 2730, which passed the Senate. This bill would provide job training and work experience to individuals during incarceration to ensure their readiness for employment upon release from prison.

Including this bill, efforts to develop a more rehabilitative prison system in the U.S. are often modeled on those of a country known for its excellent prison system: Norway.

Prisons in Norway are admired worldwide due to their success in rehabilitating incarcerated individuals and ensuring that their inmates only move forward in life, never returning to crime after their release.

Adopting a less punitive approach than the U.S., Norway’s prisons have features including solid healthcare systems, apartment-like prison cells, and vocational training programs, among other features that emphasize the long-term well-being of their inmates.

Instructional programs in prisons are another idea from Norway that is transforming the U.S. correctional system. These programs can be centered on a multitude of topics: programs for mental health, physical health, education, career-oriented training, and other crucial areas for inmates to receive help in.

“With the Norwegian model in mind, it’s easy for the U.S. to start moving in the right direction,” Roy said.

Roy also noted that the key question that Norway asks themselves is “When prisoners are released, what kind of neighbor does society want them to be?“

In response, Roy believes that “as long as we keep asking ourselves that question, our prison system is bound to change for the better, to start healing its residents instead of hurting them.”

Art makes its mark

From behavioral therapy to educational programs to sports, numerous correctional programs have the capacity to rehabilitate the incarcerated population. However, art distinguishes itself from other correctional programs with its ability to provide a creative learning experience, life-effectiveness skills that can help inmates with reentry, and an outlet for self-discovery and healing.

Larry Brewster, a social psychology and public policy professor at the University of San Francisco, stresses that all kinds of rehabilitation are essential.

“There are so many great programs out there that aren’t art-related, and the tough truth is that not every inmate is suited for art programs,” Brewster said. “But there are lots and lots of studies out there, alongside my own, that show how there are incredible benefits to be reaped from art programs in particular.”

A primary benefit of art programs is that they can improve the life-effectiveness skills of the program’s participants.

Life-effectiveness refers to the psychological and behavioral aspects of human performance that determine a person’s proficiency in any situation. Some examples of life-effectiveness skills include emotional control, achievement motivation, and intellectual flexibility.

The main purpose of rehabilitation is not just to reform those who are in prisons but also to ensure that they can reintegrate into society as smoothly and successfully as possible, and it’s crucial that the proper skills are instilled within an individual before their reentry.

Once they gain that confidence and motivation to change, it’s crucial we give them that chance to prove to society that, yes, they too can make this world a better place.

— Larry Brewster

Many researchers have associated arts education with these life-effectiveness skills, including Olivia Gude, an Associate Professor in the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

In her 2009 Lowenfield lecture, Gude acknowledged the significance of art education in empowering inmates with a sense of purpose, raised consciousness, and the belief that they can create positive change in their lives. By providing this empowerment, arts education equips inmates with motivation to better themselves, a necessary trait to have in order to achieve a successful reentry.

Art-making has also been linked with other life-effectiveness skills, such as eagerness to experiment and learn from mistakes, self-criticism, reflection, and determination to complete projects.

“When I spoke with some of the inmates who were in art programs, they all admitted that they criticized themselves while learning a new art form like painting, writing, or acting,” Brewster said. “But as they continued to paint more paintings, write more poems, or recite more monologues, eventually, they got used to making mistakes and actually better understood the value mistakes had in improving both their art and themselves.”

Along with providing life-effectiveness skills, prison arts also grant inmates an opportunity to understand themselves better.

Whether that be by helping them heal from personal trauma, reconnect with loved ones, or just express themselves through their creative voice, self-exploration is a central aspect of art.

In Griffin’s case, the letter he wrote touched on sensitive topics such as sexual abuse and self-hate. However, the letter allowed Griffin to put into words the lifelong struggles he had bottled up for so long, enabling him to understand why he had internalized this hatred for his body and how his mentality needed to change in order to heal from his trauma.

Due to their introspective nature, art programs typically circulate around themes that make most people feel vulnerable. For individuals like Griffin who have suffered from trauma, some of these themes may even hit close to home.

“Unfortunately, most people in prison have severe trauma. After studying this topic for decades, I’ve talked to a vast number of people in those facilities, and they all admit that the themes that emerged during the art programs were tough but necessary to talk about,” Brewster said. “As scary as opening up could be, the art programs provided them a safe haven to reflect on their trauma.”

On top of enabling inmates to heal through self-exploration, art programs also differ from other correctional facilities because they follow a more egalitarian learning structure.

Many instructional programs follow the authoritative system of one-way learning: the teacher teaches, and the student learns.

With art programs, on the contrary, the instructors are typically regarded as being there to assist and guide their students into creating something of their own, permitting the students to have a more interactive learning experience, feel more comfortable discussing their trauma, and develop positive relationships with their instructors are based on mutual respect as artists rather than authority figures.

“At the end of the day, all inmates just want to feel human, because in prison, it’s easy to feel anything but that,” Brewster said. “Thankfully, these art programs, with their passionate instructors and interactive activities, promote an environment of creativity and self-expression. For so many, it was the rare chance in prison where they actually felt free and, therefore, human.”

The truth is most civilians don’t view those who have been incarcerated as human, and it’s difficult for them to want or expect someone who has committed a crime to ever be their neighbor or their coworker.

But whether people like it or not, prisons all over the nation are making an effort to imprison fewer people and rehabilitate more, and with the assistance of art programs, U.S. facilities are making noteworthy strides toward that goal.

“Most people think those who have been in jail are bad people, and there are some who truly are, who truly belong in prison,” Brewster said. “But those people are a rarity.”

While art programs benefit incarcerated individuals in many ways, we can only see the full extent of the impact of art education if inmates receive the opportunity to practice the skills they have gained in spaces beyond prison walls.

“What we need to do is help those who have previously committed crimes to realize they still have a future ahead of them,” Brewster said. “Once they gain that confidence and motivation to change, it’s crucial we give them that chance to prove to society that, yes, they too can make this world a better place.”

A second chance to live

Toward the end of his letter, Griffin’s body speaks in the piece, filling the final page lines with a request so loud it would be impossible for the present-day Frederick Griffin to forget:

“I did not betray you. I protected you, and I’m asking, no, I’m begging you to now do the same for me. If you haven’t figured out who wrote this letter, listen to the beat of your heart, and you’ll know that I’ve been with you even before you became aware of yourself. Sincerely, Your Body.”

Six months ago, Griffin was released after spending nearly 16 years in prison. Although he is grateful for this “second chance at living,” his reentry has presented him with ceaseless obstacles.

“I think I described reentry as ‘beautifully challenging’ to someone the other day,” Griffin said. “Since I’ve been home, the guilt and shame of everything led me to use work as a distraction. I went right back into that mindset of not loving myself, but I know that’s not sustainable.”

However, even after being released, Griffin still refers to the letter he wrote during his incarceration, whether by pulling the letter out from under the books in his room or simply recalling his words when he needs them most.

“These past six months have been difficult,” Griffin said. “But when I think about this letter, which is quite often, I’m reminded to go back to my 6-year-old self, to talk to that 6-year-old, to honor and affirm that 6-year-old by realizing, ‘Hey, today you did the best you could, and you survived it.’”

The inexorable truth is that Griffin is still carrying the trauma of being abused. Nevertheless, he says that because of art programs like Words Uncaged and Embodied Narrative Healing, he understands that no goal, no future, and no dream is ever out of reach.

“To have that outlet, to have a platform where my expression of who I am and the person I want to be, that was the greatest gift those programs gave me,” Griffin said. “They gave me a part of my humanity that I thought I had lost.”