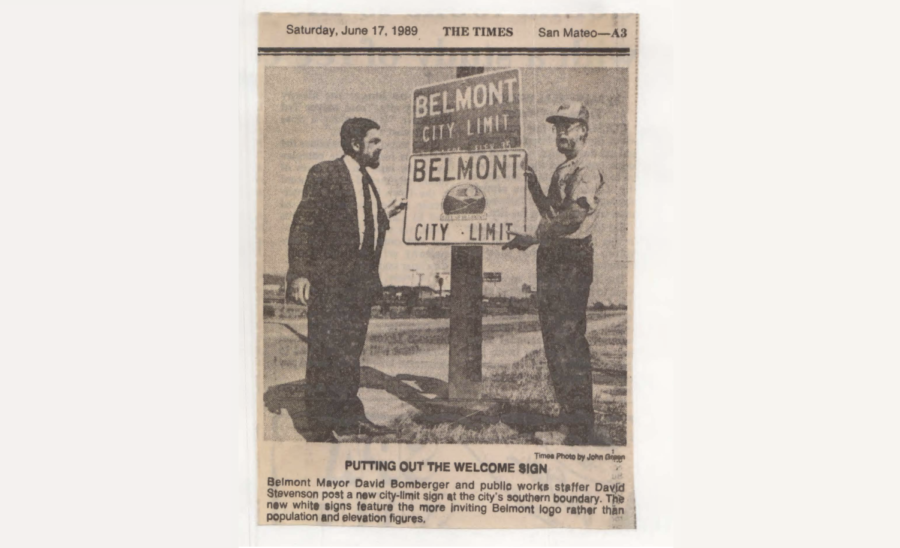

Before we start, it’s important to establish something critical: the Peninsula today — or, more specifically, the Belmont of today — is not what it was 30, 20, or even 10 years ago. Per capita personal income levels have risen dramatically, as have home prices. Ask anyone who has lived in the mid-peninsula for more than 20 years, and they will tell you that the area has become almost unrecognizably dense. And as Silicon Valley draws high-income entrepreneurs and engineers from the tech industry, those who cannot afford skyrocketing rents are forced to move elsewhere.

With this change of demographic comes a change in appearance. There arises incentive to create high-density housing with low-to-moderate-income, below market value (BMR) units where there previously existed low-density, one-or-two-story developments. Small, bucolic, sleepy Bay Area cities and towns have found themselves halfway through the play of becoming a metropolis but are only starting to realize they ever entered the theater.

Old San Mateo County has left the building.

But that’s an overly reductive explanation. These communities don’t simply convert, as one would change clothes. Nor do communities for the 21st century materialize inside a test tube. Instead, the process of community change is a long, drawn-out, and painful gestation, rife with political allegiance, slight, and ideology. It’s a new-world meets old-world clash of worldviews, where penny-candy nostalgia plows into optimistic futurism in a nuclear explosion of local passion and pride.

Hastings Drive in Belmont.

I moved to Belmont in 2012 as part of just another suburban family with a breadwinner in the tech industry. My family chose Belmont not out of any special conviction; we moved here, like so many others, because it was available, affordable (relatively speaking), and the schools were good. Anywhere else in the Bay Area would have been just as worthy a candidate were these variables equivalent.

The Belmont in which we landed was one of top-quality schools, abundant greenery, crappy roads, and traffic. One evening on our second or third month in town, a neighbor came to our door and handed us a pamphlet filled with seductive language about Belmont’s open space, local character, and Village Ambience. The woman who handed us the pamphlet gestured across the street towards a newer, three-story house erected on what was formerly the side of a mountain and asked us, “Do you really want more of those?”

This is Old Belmont.

Since January, I’ve spent countless hours scanning documents for the Belmont Historical Society and doing policy research for the city council, giving me a front row seat to the seismic transformations that are rebuilding San Mateo County and chopping Old Belmont’s legs off at the quadriceps. I also interviewed three prominent individuals of the city’s past: George Metropulos, a lifetime Belmont resident and former schoolteacher who was on the City Council between 2001 and 2005; Adele Della Santina, a 42-year resident and realtor who was a development-friendly voice on the council between 1991 and 1999; and Coralin Feierbach, a 45-year Belmont resident who was on council between 1995 and 1999, and then again from 2003 to 2013.

The archive of the Belmont Historical Society.

When we moved here, I found myself rapt by the fact that the language used to describe Belmont in pieces of shiny campaign literature was not the Belmont in which I lived. So, for the past seven months, I’ve used every means at my disposal to figure out just what happened to Old Belmont. Welcome to the autopsy table. Let’s get started.

Strife and scandal

To understand Belmont during this transformative period, one must first bear witness to just how vitriolic and bizarre the city’s politics were. As far as civil discourse is concerned, Belmont is in a golden age. It has been since 2013.

That statement holds special gravity now. As I write this, I sit in the audience of a “Forum on Civic Engagement,” hosted by the Belmont Library and featuring the entire city council. This is notable for the following reasons: first, the entire city council is in attendance and members are sitting within two feet of each other, second, no security is necessary, and third, violence — both physical and verbal — is at a minimum.

You’re probably thinking: “that sounds normal.” And you’d be correct, given the sheer banality usually attributed to municipal politics. But — and you’re going to have to partially take my word as gospel here — it was not always this way.

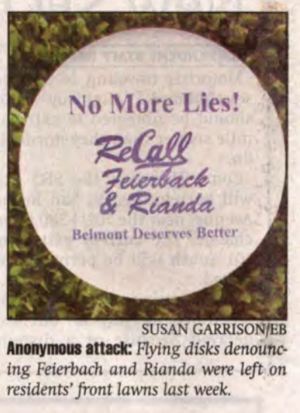

By this I mean there was once a time when feuding councilmembers got into fistfights at local carnivals. Political activists assaulted each other’s houses with Frisbees. Councilmembers would not sit together at League of Cities meetings. A 1995 Independent article likened attending Belmont city council meetings to “going to a professional wrestling match.” Pseudonymous local revolutionaries penned pamphlets accusing a certain city councilwoman of organizing municipal coups. Heavyweight journalists determined the fate of local elections. 3-4 city managers were hired and fired (seven counting interims) in the span of 10 years. A website was created showing the aforesaid councilwoman’s head in a spider web. Leaked email scandals revealed endemic elected backstabbing. And so forth.

In fact, it once got so bad that an actual group therapist was hired to help the city council with “team-building,” a strange frivolity that the taxpayers seem to have been tellingly comfortable with. (Although, for what it’s worth, the linked article says that “Peter Markovich, father of a 7-year-old boy, said he would rather see the money spent on upgrading and maintaining the city’s playing fields.”)

There are simply too many examples to list them all. Some will be explained in greater detail as this profile permits. But I can think of a few right off the bat that would probably be the most illustrative.

On July 21, 1998, the City Council — which at the time was as deeply divided as ever — had two personalities that rose above the rest: Pam Rianda, a high-school special-ed teacher with a penchant for causing city employees to quit, and Coralin Feierbach, a vocal defender of open-space notable for her efforts to preserve Sugarloaf Mountain. (Rianda would two years later be accused by someone writing under the pseudonym Waldo — on letterhead delivered to hundreds of Belmont residents — of “taking over the entire city government last month while we were busy surfing our webs and our 999 digital TV channels.” Various people have relayed to me privately their theories regarding the identity of Waldo, but I’m not sure I buy them.)

That morning, several Belmontians were less than pleased to find Frisbees decorated with purple invective lying on their front lawns. The night before, a faceless political provocateur had delivered them, sight unseen. In the months that followed, they, and similar barbs, became the impetus for a volley of accusations — some likely specious, others probably true.

Jerry Fuchs, who at the time was San Mateo County’s foremost political quarterback and wrote for San Francisco-based newspaper The Independent, himself awoke that morning to find a Frisbee in his lawn. He was accused by Feierbach, the councilwoman, of distributing them, which he disputed to The Independent in the following terms: “If I have nothing better to do than throw Frisbees on people’s lawns then she’s from another planet.”

(The Independent also carefully notes that Feierbach was “mad that the anonymous disk misspelled her name.”)

Here’s another. Former councilman Dave Bauer, who retired in 2005 for health reasons, told the press that, at Belmont’s annual Save the Music festival in 2004, then-Supervisor and now-State Senator Jerry Hill — who has a black belt in Karate — had to intervene before an altercation between Bauer and another former councilmember “came to blows.”

And if you’re still not convinced, here’s a third. For three decades, Belmont and San Carlos operated a joint fire department called the South County Fire Authority. Services and response times were generally acknowledged to be among the best in the area. Then, in 2004, amidst financial woe, Belmont and San Carlos began divorce proceedings. Just before, the Authority had proposed a parcel tax called Measure I, which would have helped replenish empty department coffers. But the measure failed, and the department, whose finances were banked on its passage, was forced to lay off six firefighters and demote three others. No money was left in the bank to pay Peg Collier, a consultant on the campaign who shelled out $15,000 of her own money to fund it.

San Carlos mayor Mike King then told Collier to file invoices with the Fire Authority to recoup the debt. Predictably, using public funds to ameliorate the fallout of a failed campaign is illegal. So Collier and King were both arrested and found guilty of intent to defraud a public board.

Here’s where it gets hairy. The Fire Authority’s finances were managed by the City of Belmont. It was Jere Kersnar, the city manager at the time, who caught and reported the fishy invoices. And the person Collier admitted the fraud to was George Metropulos, then the mayor of Belmont, on a phone call bugged by the District Attorney.

And thus, the mayor of Belmont got the mayor of San Carlos arrested.

I rest my case.

Heroes and villains

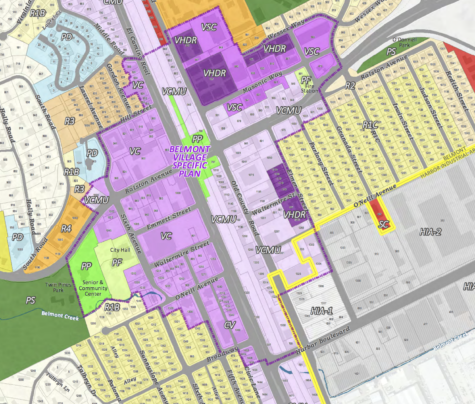

Firehouse Square, after over a decade of negotiation, is beginning to reach fruition. Apartments have come to life at the corner of Davey Glen Road and El Camino Real, replacing a dilapidated credit union and a 7-11 whose most notable feature was the number of calls it generated for the Belmont Police Department. The Davey Glen neighborhood now has a park after 25 years of stalling. Two new hotels are being built on Shoreway Road. Plans are finally in the works to redevelop properties on Middle Road that have sat vacant under city ownership for years. Last November, the city council approved the Belmont Village Specific Plan, which rezones Belmont’s downtown in order to facilitate future growth where there currently exists a smattering of commercial storefronts and an enormous Safeway. The list goes on.

Former Councilwoman Coralin Feierbach, whose lengthy tenure allowed her to preside over the council as mayor in 1999, 2007, and 2011, says these are symptoms of a problem. Or, rather, that the lack of backlash — and, in all fairness, community opposition to the projects has been decidedly tepid, for Belmont — is cause for concern.

“It’s like someone sprayed the city with an anesthetic,” said Feierbach. “It’s been asleep for five years.”

Five years ago, in 2013, Feierbach and her longtime colleague on the council, Dave Warden, did not seek re-election. Instead, they endorsed Gladwyn d’Souza and Kristin Mercer, both of whom were of the same growth-ambivalent sect as the outgoing councilmembers. Neither received enough votes to win a seat, although Mercer did ride the coattails of a pro-growth incumbent. Elected to fill their seats instead were Charles Stone and the late Eric Reed, both of whom represented a pro-growth, development-friendly local attitude, making this philosophy the prevailing one for the first time in years. (Christine Wozniak, the last remaining councilmember of the formerly-dominant clique, would later resign in 2014.)

Feierbach told me that she blames the no-growth dimming on primarily local turnover.

“There’s new people that have moved here. There’s a lot of older people that have moved out.” said Feierbach, “people have been lulled into complacency.”

The presupposition necessary for this argument to work, of course, is that the new crop of candidates must have bad qualities towards which people have become complacent. Adele Della Santina, who was on the council during most of the 1990s and was mayor in 1995, disputes such assumptions.

“I always say, ‘Listen to the newer generation of voters. Let them take Belmont where they want it to go.’ The rest of us will be gone,” said Della Santina.

There are two core sides to the argument, and these above aphorisms distill them perfectly. In one corner is the argument that the virtues and visions of past leaders have been corrupted by special interest-tainted political neophytes — that, in a broad sense, the newcomers are wrong. In the other corner, that mascots of the past should step back and let the next generation govern for themselves — or, in other words, that the newcomers are right.

It’s also somewhat unfair to characterize “newcomers” in such broad fashion. Certainly, while some of the latest homebuyers and renters of Belmont have incentive to vote for candidates that promise more housing, this is not the whole truth. But this is the direction things are headed in this moment, as demonstrated by the latest flux of development, and for this reason, argues Della Santina, “We had our chance. We can’t keep it forever.”

Portraits at the Belmont Historical Society of a city in evolution.

Now, that said, it should be noted that Della Santina is herself aligned with the newcomers that have now come to dominate the council. Her views and endorsements — which include most of the current city council — place her squarely in the pro-development camp. And, according to her, when she began vying for commissions and boards, “the county knew Belmont was no-growth, and they told me I was a voice of reason.”

“Some people who most pronounce their dissatisfaction, historically, are those that will soon be moving away,” said Della Santina.

And with that turnover comes development like what is currently being constructed at the corner of Davey Glen Road and El Camino Real, about which, says Feierbach, “ten years ago or even seven years ago, I would have gotten phone calls left and right.”

When Feierbach’s view was dominant on the council, Belmont had accrued somewhat of a reputation for turning developers away at the door. Her involvement with city politics began in the late 1970s, when she and other activists helped ward off proposals to develop Sugarloaf Mountain, which since then has been left as protected open-space. She accused the current council of embracing new development, when in her day, “We didn’t necessarily embrace. My thing was, let it be pretty, let it be nice, let it be something we can be proud of.”

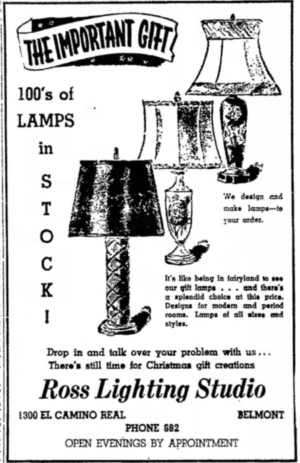

That makes sense, but I do have to wonder whether it is by this philosophy that the lot at the corner of El Camino and O’Neill remains vacant. What had been the existing structure, for a business called Ross Lighting, was demolished in 2001; since then it has been an eyesore — the southern corner of a lot that is one of Belmont’s only legitimate claims to blight.

“I don’t know what the restrictions were at the time to build there,” said Feierbach, regarding the Ross Lighting property. “We got several offers, but they were not great.”

George Metropulos, who overlapped with Feierbach in 2001-2005 on the council, made similar remarks.

Metropulos said, “When that development was first proposed, a guy wanted to build all along [Fifth Avenue] these big units, each of which had a studio on top. Where are these people going to park? Traffic and parking are the big issues in mind.”

Pam Rianda was another controlled-growth confidante during this period. A San Jose Mercury News article from 1997 notes that, “By rallying about 300 residents to public hearings, she won a battle to reduce a three-story apartment and retail complex at Ralston and El Camino Real to one story so Belmont preserves its village ambience.”

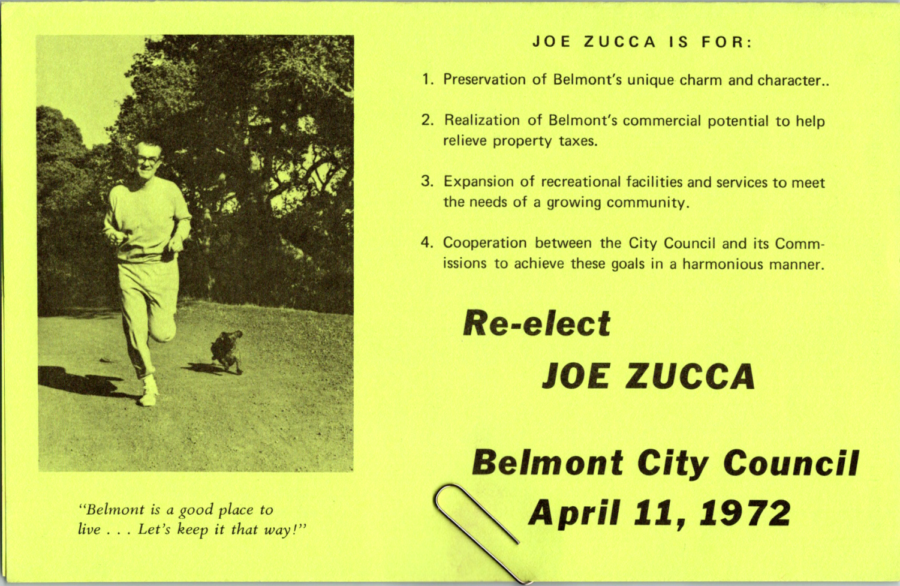

It became abundantly clear to me that, while no-one would readily doubt Belmont’s unique character, its Village Ambience (or equivalent campaign jargon) has become a sort of catch-all for the developmentally disinclined. So then what is this Village Ambience? What prompted municipal denial when, ostensibly, it met all of the goals stipulated in the city’s solicitations of developer interest? What, in other words, were they so interested in preserving?

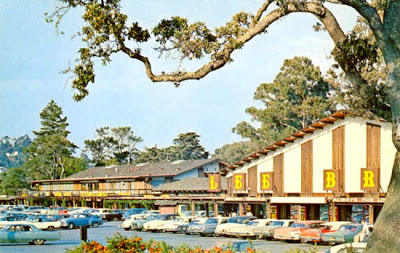

It’s a thing that goes by many names. To figure out exactly what vision it is the city’s leaders were trying to preserve, and thus derive the source of Old Belmont’s fear of development, we must shift our focus from the recent to the mid-century — to when the city was a quiet, idyllic suburban community — and let others wax nostalgic.

Americana

There is a Facebook group, populated by current and former residents of Belmont, dedicated to sharing memories of what it was like in decades past. It’s an amazing resource of local history. But while the typical, rose-tinted nostalgia for youth is sometimes on full display, it occasionally crosses into the territory of something else — something difficult to identify — something tinged with anger. One of the group’s most popular posts asks members, “do you miss the old Belmont?” (I’ve edited this slightly for the sake of syntax and grammar, but the tenor is the same.) Thus far, it has amassed a total of 194 replies, and by far the most prevalent point of objection to “the new Belmont” is that it is too populated, too expensive, and too dense.

The truth of those allegations is, obviously, subjective. Living in the Bay Area has its sacrifices. But even if they can’t be quantified empirically, few would be so bold as not to acknowledge them. Perhaps the foremost evolution lies in the area’s astronomical home prices, which — sitting at an average of $1,898,000 according to Coldwell Banker as of this writing — are 481 percent over the national average. As a result, census data shows that median incomes have risen dramatically, the population has diversified, and the tech sector has become, overwhelmingly, the predominant employer.

Community leaders of Old Belmont have watched their city become unfamiliar. Feierbach moved to the city in the early 1970s with her husband from Berkeley. Della Santina moved to Belmont in the late 1970s. Our third requires a bit of introduction.

For those who went to Carlmont in the 1970s, lived in Belmont during the years he taught at Central Elementary School, or have ever gone to an event hosted within city limits, Metropulos is likely a familiar name. His years spent as a teacher and endless record of community involvement render him probably the closest thing Belmont has to a local celebrity. For this reason, in 2001, a unique campaign for city council bearing the slogan “Metro Knows Belmont” was won with huge margins. (It was also in that election that Bauer, a pro-development voice, was elected to a council seat; he beat Pam Rianda, who had no doubt been hurt due to the independent aforesaid Frisbee- and pamphlet-based efforts of Belmont’s anonymous rhetorician, Waldo.)

I met Metropulos outside of Peet’s Coffee in early February. He spoke with nostalgia of the idyllic youth he enjoyed in 1960s Belmont, a time when “you’d leave the house on a summer day at nine o’clock and be home at dinnertime; we used to ride our bikes everywhere, buy penny candy.”

This touches on a definite use of the finished, preterite, over-and-done-with attitude I noticed in the sort of nostalgia present both on the online communities and in those I’ve spoken to for this piece. Metropulos, for example, remembers when “there was a movie theater.” There is, indeed, no longer a movie theater. It is now a Planet Granite. But some things are more abstract; less quantifiable in terms that have street addresses.

“It was a great place to grow up,” said Metropulos. “You knew people. It was just a nice, mellow town.”

Metropulos is from Belmont, through-and-through. His childhood, adolescence, and schooling were all within city limits.

He laments the sort of construction now occurring in cities like San Mateo and San Carlos, where new development has been on the rise. San Carlos, for example, is currently building Wheeler Plaza, an enormous 2.4 acre parking-commercial-retail structure that was approved in 2016 and is currently under construction.

“These buildings are so big, and so close to the sidewalk,” said Metropulos, “that when you’re walking through on a sunny day it’s like you’re cold.”

But, he assures me, this doesn’t place him into any pejorative camp. “There’re a lot of people that are super pro-development, and they call people who are not as pro-development ‘old-guard,’ ‘not-in-my-backyard,’ ‘build-anywhere but here,” said Metropulos, “and I kind of resent that, personally.”

(Not-in-my-backyard has become synonymous with pro- and anti-development arguments, especially in online circles, as denoted by the acronym NIMBY. Some pro-development Peninsulans now call themselves YIMBYs. It’s all a bit kindergarten).

“Now the big development is moving. I know you need development. I know that. I am more concerned with the density and the depth of the development,” Metropulos told me. To him, the archetype of overbuilding is San Carlos, where he tells me “you can’t drive anywhere.” The challenge, says Metropulos, is “how to maintain the charm and feel of a small town while also updating, modernizing, and providing more housing.”

In the interest of objectivity, I do want to note here that none of the council, at least rhetorically, have devalued preservation. All five of the current city councilmembers have used some derivative of “preserve our open space,” “maintain our unique appearance,” and other similar sentiments in their campaign literature. And even if such things aren’t guarantors of policies in office, it is obvious that no sane elected official in Belmont would rubber-stamp any sort of proposal to develop the city’s heralded open space, parks, or quiet suburban neighborhoods. One need look no more than a few weeks ago to find proof of this. The council unanimously amended the zoning code to permit HRO-2 density transfers between lots on separate streets. This means that, if one were to own two lots both of the HRO-2 designation located anywhere within city limits, they may permanently transfer the density of one lot to the other, thus in the long term restricting the number of buildable hillside lots in the city.

Many council hours in all eras have been spent finding a happy medium in which more housing can be constructed and density can be increased, without sacrificing Belmont’s Village Ambience. Driving eastbound down Ralston, one notices that the unique character begins to dissipate as one approaches El Camino. There are more parking lots, commercial structures, and vacant areas. The city’s uniqueness, faux-Victorian architecture on the former Five Guys notwithstanding, is nowhere to be seen. From what I can tell, El Camino has a distinct lack of greenery and wide-open spaces. It’s decidedly unpicturesque.

It is here that you’d imagine a compromise could have been reached. But you would be… wrong.

Downtown

I say “downtown” not in reference to any specific thing, because Belmont, infamously, has no downtown. Instead, I say “downtown” in reference to a geographic region that is inclusively referred to as Downtown (or “Village Center”) on city zoning basemaps. Downtown Belmont, really, does not exist.

The causes for this are numerous, some historic and some still extant, but one is by far the most important: Belmont’s geography, at least for much of its life, has precluded the organic development any sort of a community center. Carlmont Village Shopping Center is a convenient stop for western neighborhoods; the region ostensibly known as Belmont Village services those east. And in both cases, our commercial offerings pale in comparison to what is available elsewhere on the peninsula, where spotless rows of boutiques and immaculately-kept storefronts reign supreme. Both of Belmont’s neighboring cities, San Mateo and San Carlos, have celebrated downtowns, while others in San Mateo County, like Redwood City, have made names for themselves with massive downtown revitalization campaigns.

But Belmont’s supposed nucleus, in spite of decades of campaign promises and shallow rhetoric vowing downtown redevelopment, has been a stagnant and putrefying corpse since at least the 1950s — candidate statements earnestly pledging downtown revivals are a staple of every mailed flyer I can find in the Belmont Historical Society archive.

It seems natural — to me, anyway — that downtown should be a point on which all interested parties can find some common ground. Regardless your attitude towards development in the canyon, or on whether Belmont has a Village Ambience that must be preserved, creating some kind of city center seems a natural step in the remediation of a community that has had its fair share of developmental defects.

But unfortunately, as the broad is made specific, minor disagreements explode into major inhibitions. Firehouse Square, a proposal located on the edge of the Village Center district, is a perfect example.

The lot on which Firehouse Square is now planned was, for about half a century, home to City Hall. But as the building began to reach antiquity in the mid-1990s, it became an unavoidable truth that the existing facilities were inadequate and unable to contain a growing municipal bureaucracy, some of which were scattered around the city due to a lack of available office space. So City Hall gradually usurped an existing office building a block away, on Sixth Avenue, and old City Hall was unceremoniously demolished in the early 2000s, leaving lump of dirt where there once was a building.

It is still a lump of dirt.

Why? Because the dominant political forces at play, when faced with a decision between multiple high-density, residentially-focused proposals for redeveloping the site, chose none of them.

“Once you build it, you can’t get rid of it. It’s there,” said Feierbach. “It’s better to have nothing than to have something that is not good for the city. What I was trying to do is get something in-between.”

But in their attempts to get something “in-between,” councils let slip prime opportunities to allow construction that would have generated tax revenues and restored the city’s more blighted regions. Two consecutive proposals to develop the Ross Lighting site, which sits adjacent to Firehouse Square and is part of the current redevelopment proposal, were either turned away or abandoned by the developer between 2000 and 2008, when recession caused developer interest to sag across the peninsula.

Now, the city has spent the last six years in negotiation with developer Sares Regis to construct an 81-unit, mixed-use development combining below-market-rate condos and ground-floor retail, and Firehouse Square is approaching fruition. Feierbach is not pleased.

“They’re going to build more of that crap,” said Feierbach. “They want to build 83 units in Firehouse Square. Why? Get it down. Get it down to something reasonable.”

The current iteration of Firehouse Square is a bit of a new direction, as negotiations with the city’s partner had previously become tenuous, calling the fate of the project into question. What ultimately became the saving grace of the project was a proposal to, through a combination of tax credits, municipal subsidies, and a partnership with MidPen Housing, make 90 percent of the units in Firehouse Square affordable. (My interviews were conducted in February and March, so at the time this was not a part of the equation. However, while the affordability and various technical details of the project have changed in the interim, the core density — that is, the number of units and bulk of the project — has not.)

“You want to talk to people that have lived here 40, 50, 60 years, and they want to maintain their quaint community, if they can,” said Metropulos. “The longer you’ve been here, the more apprehensive you are about density, overdevelopment, and things like that.”

The next generation, and some bad platitudes

Feierbach, Metropulos, and Della Santina, irrespective of political ideology and attitude towards development, are similar in that each play for a dying team. Old Belmont is on the brink of extinction.

That statement is not meant as an impetus for some kind of radical grassroots action. It is not a rallying cry. It is fact. The basis of the Bay Area’s 21st century shift is that, just as Old San Mateo County has found itself at odds with the tech industry, the interests and realities of Old Belmont do not square with the needs of New Belmont, and since one is a rising quantity and one is a diminishing quantity there can only be one outcome.

Sugarloaf Mountain.

Local wisdom holds that the etymology of “Belmont” derives from the Italian “bel monte,” which translates to “beautiful mountain.” And there is some circumstantial evidence to support this, given that the palatial Ralston Hall on the NDNU campus was once the mansion of Count Leonetto Cipriani, an Italian aristocrat. To Metropulos, these mountains are the essence of what future generations must refuse to sacrifice.

“Make sure you can still see them. There are all these streets in Belmont called ‘Bayview,’ ‘Valley View’; but you can’t see the bay anymore and you can’t see the valley,” Metropulos said, gesturing at the mountains in the distance from our table at Peet’s. “Remember what that is. But I don’t know if that will matter to them.”

“I fought my life to get as much as we could so that we didn’t get mass-scale development,” said Feierbach, referring to the city’s 2013 purchase of San Juan Canyon for $1.5 million. “These are people who give the impression they’re for open space and conservation, but they’re really not. And then there’s a group that really is.”

That tenor of resignation reflects the assumption among some that, commensurate with the decline of Old Belmont, the next generation of leaders won’t prioritize those qualities which, to them, define the city. To prove this, one need only read campaign flyers from the ’70s and ’80s and notice that every single one — with very few exceptions — has language protecting “rural character” or equivalent. The flip side of the coin suggests the current crop of leaders do prioritize these aspects of Belmont, but also realize the importance of growing dynamically with the times.

“The city council is great. Eric Reed, bless his heart, was so good. They’re seeing the new spirit in town, and I back them,” said Della Santina. “My reason was that I could see they were young, family people — the Belmont of tomorrow.”

I think the point is this: one cannot claim to be pro-growth without someone to accuse of being anti-growth; there cannot be YIMBYs without NIMBYs; there is no new if it does not replace old. Local politics is a muddy discipline of tenacity and turpitude, and were it not for the good faith (and bad faith) efforts of Belmont’s forebears, certainly we would lose some of the distinct Local Character and Village Ambience that reads so nicely in a candidate statement.

Local politics, as with all American politics, is not necessarily an isolation chamber in which the most vacuous can duke out their spites. Sometimes sentimentality doesn’t stand up to — or fails to stand in for — reason. Perhaps we are being held hostage by a minority, or maybe we really are at the whim of the five councilmembers of the development apocalypse; my guess is that the answer lies, like as in so many debates, somewhere in the middle. And in the vast majority of cases, these are people who care about their community, be the lens of their ideology focused on the past or the future.

Indisputably there is great value in respecting the past as we move forward. Be in it for the right reasons and you will likely harness an ability to effect real change. Be in it for the wrong reasons and risk humiliation in the eyes of posterity.

Play your cards right and you’ll get a free Frisbee.

Edits were made to reflect the following minor factual inaccuracies: the recall threat did not occur on an election year; Pam Rianda was a special-ed teacher, not a PE teacher; a photo of the city council in 1997 was actually of candidates and was removed; Dave Bauer was elected in 2001, not Terri Cook, who was re-elected; and the city has negotiated with Sares Regis for six years, not two.

Ron Tussy • Jul 15, 2020 at 5:35 pm

Terri,

You are not speaking about urban areas in your statements. I am talking about high density urban areas such as Belmont, who has an equal amount of density as San Francisco in some areas. My data is accurate. The Chicken decision is not that old. It happened within the past 10 years. Nearly all of Portola Valley, most of Woodside, some of Hillsborough and major parts of Menlo Park are NOT high density urban areas like Belmont is in some areas. They are areas that have lots of acreage per parcel. I think your argument is not relevant to the issue. Chickens are a nuisance. Belmont PD has defined this as well and has responded as such in many cases involving people owning chickens in Belmont. They draw rats and insects and impact wildlife such as coyotes who hang out in front of houses with chickens by smelling them. The also draw bobcats and mt. lions.

RIiey Prime • Apr 23, 2019 at 10:58 am

Where’s Waldo?

Sachin Deshpande • Nov 24, 2018 at 2:58 pm

Thorough research and article. Thank you! Just curious (maybe for future articles) on impact of expansion on city finances. San Carlos and San Mateo are allowing more development. Belmont less. Has their been a massive budget impact to Belmont?

Suzanne Zaino • Oct 22, 2018 at 3:55 pm

Thanks, Sam, for giving us the very interesting history of Belmont politics. I have lived here for nearly 19 years and got to witness some of this as a family with small children growing up in the schools, desperately rallying for field space (still not completed) and attending meets at city hall. When I contemplated remodeling when we first moved to town, 6 contractors outright refused to consider working in Belmont because it was so difficult. I live next to the open space and value it, but know that we need to find a way for teachers, fire fighters, police officers, and many other vital but lower paying professions to be able to actually afford to live here. I do appreciate the balanced description of the history.

Lisa Meltzer Penn • Oct 6, 2018 at 2:19 pm

Sam Hosmer,

Hats off to you! You are a fine journalist and I am so impressed with the massive amount of work you undertook to write this sweeping portrait of our city’s history. I learned a LOT!

Terri • Sep 11, 2018 at 1:31 pm

Hello Ron,

The number of chickens allowed has not been discussed for many, many years, so allowing 6 has been in place for some time. I suspect that you might be incorrect about “most cities” not allowing any chickens, and Belmont is not “one of only 2 cities in California that allow more than 2”. I think most cities allow. A lot of people have coops and raise their own chickens for fresh eggs. I just checked with several cities in SM County, and several allow. Portola Valley has no limit. Menlo Park allows 50 for every quarter acre. Hillsborough has no limit. Woodside is 25 per acre, max 50. Most cities don’t allow roosters for obvious reasons. If there is an issue with whoever is keeping chickens next to an apartment building, you can contact code enforcement. There are lot size parameters, as well as maintenance provisions in the ordinance.

Ron Tussy • Sep 7, 2018 at 1:50 pm

Hey Dave,

Seems like 3 other people on the council disagreed with you pretty often. Just wondering…when you were council member, where you the one that spearheaded the city ordinance, that still remains in place, that allows up to 6 chickens in a Belmont residence backyard? Belmont is one of only two cities in California that allow more than 2 chickens in someone’s backyard, and most cities don’t allow any. Great history of well thought out city planning in Belmont, high density apartments next to chicken coops.

Biology Geek • Sep 7, 2018 at 10:37 am

As a quick response to the Ron Tussy’s comment, “My property backs up to Waterdog and since moving here 22 years ago, I have noticed a distinct reduction in the amount of wildlife in our surrounding hills. We used to see wild turkey, bobcat, cougar, herds of deer and packs of coyote. Our open space meant that wildlife could live and flourish. Only a spotting of deer are left, when we used to see herds of 16 deer together roaming.”

It should be noted that the number of mountain lions/pumas has been on the rise over the last 20 years which would lead to fewer deer and smaller animals. We have seen mountain lions/pumas wandering into San Mateo’s downtown more than once or even twice over the last few years and as well they are regular visitors to the areas backing up to Sugarloaf and of course around Hillsborough as well. But they try to remain unseen when possible, camera-shy, and more active around dusk and dawn.

This is a really nice resource for information about local pumas: http://www.santacruzpumas.org/

OTHERWISE, and for reference, I live locally (all of my life) and work in Belmont near the train station, i.e. the “downtown” area. We have been getting calls at work about meetings for the proposed downtown future changes, etc., and I can see the benefit. Traffic is a bear everywhere these days on the peninsula and, yes, the mountain views from the lowlands are gorgeous. I get to see the fog creeping in and out over the mountains and through the canyon in the mornings and walk through Twin Pines Park on my lunch break. I use Ralston to get to my parent’s house and to my wonderful mechanics and Dianda’s (when I’m desperate for some amazing pastry comfort food or a gift for a friend). If that were available in Belmont “downtown” I wouldn’t have to drive all the way up and over Ralston to get it (hint hint).

We all are suffering through this change of the guard. We can’t revoke Silicon Valley’s residency (though I know many of us wish 100% that we could). We suffer through the traffic and development and complain and get frustrated and bullish sometimes. Belmont is lucky to have wonderful homes/homeowners, schools, and amenities for families. If your property values have gone up be thankful. We can’t take only the good from the situation and not also accept the flip side of the coin.

But I am glad that there seems to have been a resurgence in mindfulness toward people who aren’t homeowners and aren’t making 100k+ p/year paychecks with regard to the O’Neill/El Camino project. Property and buildable space is at a premium and I am glad that space is being carved out for middle class and working class people (artists, social workers, teachers, food service/hospitality workers, etc) with the cost of living being what it is.

Thanks for the fantastic article- it was way more interesting and enjoyable than I had anticipated! Great work, Great writing!

-Geek

Michael • Sep 7, 2018 at 7:26 am

Great read! When I first moved to Belmont one of my coworkers razzed me asking “Why are you moving to a retirement community?”

This article helped me finally understand that joke, and also why things are so dilapidated compared to neighboring cities like San Carlos (which was and still is considered more desirable when buying a home).

Thanks Sam.

Kristin Caldwell • Sep 6, 2018 at 9:56 pm

I have been a San Carlos resident since 2007 and have heard rumblings of this history but never a full political history on the topic. Gained new perspective – thank you so much for your concise, well written article!

Ron Tussy • Sep 6, 2018 at 3:02 pm

Informative article. You must get paid by the word. (joke) I have been a Belmont resident since 1997 and have raised two great kids here. I think it is no coincidence that the city council was occupied by recently relocated realtors and a guy who was Google’s chief real estate investment officer. One of the biggest problems I see is the lack of a reality check in Belmont’s planning. The proposed downtown is an example. The reality is that none of the other municipalities you mention on either side of Belmont have a major, federally funded thoroughfare running right through a proposed downtown area. Ralston avenue is not just one of the highest trafficked streets on the mid peninsula, it is also a evacuation route in case of major catastrophe, such as an earthquake. It is a major commute route. Most of us still working residents of Belmont have to commute and this proposition is getting worse and worse by the day. If you are an older resident, emergency response times are now above the acceptable threshold in Belmont. If you don’t believe me, go ask Belmont’s Fire Chief. Just before Crystal Springs School was built, I personally witnessed a first responder fire truck going to an emergency wedged in unmovable traffic in front of Ralston Middle School for more than 20 minutes. Nationally acceptable response times are between 6-7 minutes. If it was a heart attack that was being responded to, that person would have died. My property backs up to Waterdog and since moving here 22 years ago, I have noticed a distinct reduction in the amount of wildlife in our surrounding hills. We used to see wild turkey, bobcat, cougar, herds of deer and packs of coyote. Our open space meant that wildlife could live and flourish. Only a spotting of deer are left, when we used to see herds of 16 deer together roaming. I think it is important for a town to keep its heritage. Back in the early 1900’s, Belmont was once a place of refuge for city dwellers on weekends to get out into the countryside. I take pride that Belmont residents have accomplished so much, yet only 26k residents live here. We are known all over the Bay Area as being a place that has kept its charm, where other cities have bought into the pro growth and city revenue temptations. When asked where I live, people respond, “Ahhh Belmont, nice place! Still kinda charming. Great canyons and hills”.

Dave Bauer • Sep 6, 2018 at 2:15 pm

Very nicely written.

I would like to know why Fierbach was held as the conscience of the Council and the town for this article. While she and Warden dominated the opinion on Council while I was there. Their guidance of our town left a great deal to be desired.

I did discover that no matter how much they caused development nightmares and policy decisions not in the best interest of our town, Belmont would survive. That was the only comfort I derived from my service to Belmont while on Council.

If you look back in the archives, you’ll see many 4-1 votes. I rarely agreed with their policy directions.

I was highly gratified by my relationships that I developed with the other Council members in our area. The work I did with the League of Cities at the State level on behalf of our town.

It’s interesting that so far my mark in the history of Belmont City Council was that moment in the park at the “ Save the Music “ event. It makes me chuckle.

Thanks for writing such a well laid out discriptive article.

My Best

Dave Bauer

Former City of Belmont Councilmember

Judi Allen • Sep 6, 2018 at 12:20 pm

A very well-written commentary about the evolution of Belmont*, except for the sentence leading into the FireHouse Square paragraph. It states “…the lot at the corner at Ralston Ave and O’Neill remains vacant”. It should read “El Camino Real & O’Neill”. I moved to Belmont in 1969, and lived there 48 years before moving for awhile to South Lake Tahoe – another community suffering the same type of growing pains as Belmont! During that space of time, the City of Belmont changed the zoning of my duplex several times: From R-3 to R-4 to R-2 and now, it is zoned R-1 (even though there are 2 full units there and it should be zoned multi-family complex). They did that so they could transfer zoning units to a proposed large town home village development that the then City Manager, Jim DeChaine bought & moved into! We never received notification of a public hearing to rezone our property on Alameda de las Pulgas just off Ralston. Maybe we can get that done in this new environment, and I can build a 6-story condo complex where my duplex currently sits?

I agree that the current City Council is a cohesive group who makes thoughtful decisions about Belmont. Yes, Eric Reed was an incredible component of that Council, and he left his mark! His replacement is doing the job that Eric started…

The increased traffic on upper Ralston Avenue presents many problems: Commuting past 3 schools which drop-off times that merge with commute times, is a nightmare. Watching our Fire responders try to navigate Fire Engines down a clogged Ralston Avenue, is just rediculous – as so many drivers don’t know to get out of the way, or don’t know how to, because there is no where to go unless you drive forward into traffic to allow the engines to get through! There are traffic signal systems that allow the fire station to initiate signal changes to allow the lights to change to move traffic – and Belmont should definitely look into this. For the Cipriani station to respond to Carlmont Shopping Center, the library and churches in Carlmont, the Assisted Living on the corner of Alameda & Ralston, AND our homes in Central Belmont, is severely compromused.

But, overall – I am proud of Belmont. Our “community” built the amazing library; saved Twin Pines Park (the FIRST People’s Park – purchased by the people of Belmont by ballot vote), and built a great park & community center, stage & program; Purchased Barrett School to turn it into a Community Center; Built the sports center on the East side of Hwy 101. These were all community initiatives, as we had NO community centers when my daughter was 13 years old! Yes, I am proud of Belmont!

Sam Hosmer • Sep 6, 2018 at 2:31 pm

Thank you for your feedback and the note regarding the El Camino/Ralston typo. It has been fixed.