Maxwell Gruver was a typical college student starting his first year at LSU with dreams of pursuing a career in political communications. He loved every aspect of college life.

“He wrote for the high school paper. He loved it. At LSU, he was into journalism and the communications program,” said Max’s mother, Rae Ann Gruver.

Max enjoyed his classes and thrived academically. In addition, he was social and had made many friends. To expand his circle, Max rushed to join Greek life at the fraternity Phi Delta Theta.

His mother was excited to see her son enjoying college. One day during work, Rae Ann got a call from Baton Rouge.

“I just knew something was wrong,” Rae Ann Gruver said.

A nurse at the hospital told Rae Ann her son had been found unresponsive as a result of a hazing incident. Rae Ann and her husband immediately took a flight to Louisiana. Max died shortly after being admitted to the hospital.

According to the U.S. District Court, the Phi Delta Theta fraternity required Max and other pledges to take multiple chugs from a bottle of 190-proof liquor.

According to a 2021 NBC report, more than 50 student deaths from fraternity hazing have occurred since 2020, most resulting from alcohol poisoning. Trevor Duffy, a student pledging at the University of Albany, died after drinking 60 ounces of vodka–equivalent to 15 shots–in a hazing ritual. Stone Foltz, a Bowling Green State University student, died after attempting to drink a whole bottle of alcohol. His blood alcohol level was .35, over four times the legal limit for driving, which is .08.

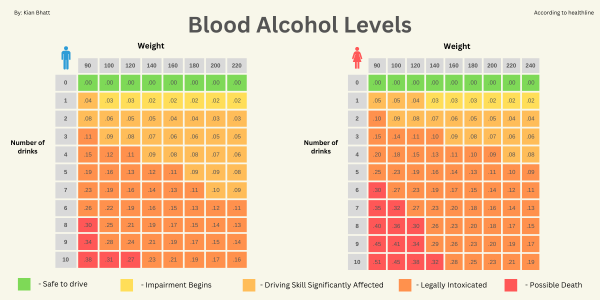

Many hazing deaths, such as Foltz’s, occur when blood alcohol levels exceed a certain threshold. According to Case Western Reserve University, a student’s blood alcohol level can depend on how much and how quickly they drink, their gender and weight, and whether they have any food in their stomach beforehand.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines a “standard drink” as one can of beer, an 8-10 ounce hard seltzer, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a 1.5-ounce shot of hard alcohol (gin, rum, tequila, vodka, etc.). Each “standard drink” contains .6 ounces of pure ethanol, considered roughly equivalent in their impact.

A chart from healthline shows that a 120-lb woman might be severely impaired or die from intoxication after seven “standard drinks,” such as 1.5 oz shots of hard alcohol. In some of the hazing-related deaths at fraternities, students were asked to chug bottles of hard alcohol, which may have exceeded the equivalent of 30-40 “standard drinks,” without them realizing how much they had consumed.

According to a 2008 study by the University of Maine, 73% of students in fraternities or sororities have experienced events that match the definition of hazing. Because the definition of hazing is ambiguous and there are unreported incidents, this statistic and others are likely underestimated.

Many students don’t realize what qualifies as hazing and aren’t sure when a line has been crossed. A report by Stop Hazing estimates that 9 out of 10 students who experience hazing do not consider themselves to be hazed.

Despite the dangers of hazing, students still want to join Greek life for a sense of community, social activities, and a life-long support network.

To some though, hazing seems unnecessary.

“Students should be able to enjoy Greek life without having to take part in unsafe activities,” said Carlmont senior Garrett Paulus.

Several non-profit organizations are working towards making Greek life more safe. Hazing Prevention Network (HPN), StopHazing, and the Max Gruver Foundation are dedicated to educating people about the dangers of hazing, advocating for change, and engaging the community in strategies to prevent hazing.

In addition, according to Stop Hazing, 44 out of 50 states in the U.S. now have hazing prevention laws that enforce punishments for any hazing.

One of these laws is the Max Gruver Act, created by Max Gruver’s family, which charges anyone who commits hazing with a misdemeanor of a high or aggravated nature, which may result in a $5,000 fine and up to one year in jail.

The laws can’t entirely prevent hazing, so students need to be aware of the potential dangers. Rae Ann Gruver said the best way to stay safe while rushing is “to find out and be educated about the fraternity or sorority. Then, feel empowered to stand up to it if hazing happens. Even if that’s a hard thing.”