“Do you want to be an organ donor?”

While getting your driving permit, you see this question appear next to a checkbox.

You mark “no” without giving the question a second thought. But for the over 100,000 people in the U.S waiting for an organ transplant to save their lives, it’s not just a checkmark.

According to the American Transplant Foundation (ATF), 17 people die each day waiting for an organ transplant.

“Organ donation is the process of giving an organ or a part of an organ to be transplanted into another person. This can happen with a deceased donor, who can give kidneys, pancreas, liver, lungs, heart, intestinal organs, or with a living donor, who can give a kidney or a portion of the liver, lung, or intestine,” the Organ Donation Health Resources and Service Administration (ODHRSA) said.

The most common reason people need organ donations includes genetic conditions, infections, physical injuries to organs, and damage due to chronic conditions such as diabetes.

Organ donation is a topic that does not attract a lot of attention, despite the decision to register to be a donor residing in the hands of 15 ½ -year-olds applying for their driving permit.

While many people are under the impression that there is a surplus of available organs, that is not the case. According to ATF, there are over 100,000 Americans waiting for organ transplants on the National Organ Registry.

For the organs of a deceased person to be transplanted, they must be discovered before the organs expire, ranging between a few hours to a day. Additionally, the donated organs must be matched with individuals on the organ waiting list. Matching is based on a range of factors including blood type, tissue type, medical need, and length of time on the waiting list.

To qualify, sick patients have to be medically scored, and be in a severe enough condition to score between 36 and 40 on a 40-point scale. Yet, for people with a score of just 18 and above, a transplant will significantly increase their chance of survival.

Mitch Giampaoli, a liver transplant recipient, didn’t bother signing with the National Organ Registry because he knew he would need the liver long before he would be able to get it.

“The country only has so many available organs to donate. So when you’re on that national list, you’re talking about everybody in the U.S. who’s fighting for a liver and so they use a scoring system,” Giampaoli said.

After being diagnosed with hepatopulmonary syndrome, a condition affecting his liver and lungs, Giampaoli was still considered too healthy to qualify for a liver transplant, despite his skin turning a yellow-grayish hue. Giampaoli kept his body in shape by walking countless laps around the College of San Mateo and Hillsdale High School track while pushing an oxygen bottle which he later named Frank the Tank.

“I started to take on a grayish hue, like a dark cloudy day. Yet, I was in too good of shape to qualify for a recent transplant. My disease, hepatopulmonary syndrome, did get me bonus points, but I was still only at a score of 22, and transplants were only given at 37 and above. It would have been a long time had my friend Greg not stepped in and got tested for me,” Giampaoli said.

A deceased person registered as a donor can provide more than just one organ for transplant. According to ODHRSA, each organ donor can save eight lives and enhance 75 more.

There are a lot of myths and other misconceptions that deter many people from becoming organ donors. For example, a survey conducted by Donate Life America found that 52% of Americans feared that their physicians would not try as hard to save their lives if they were organ or tissue donors.

“When I was a young man and I was getting my license, I didn’t opt to be an organ donor because I was worried that the doctors wouldn’t try to save me on the table,” Giampaoli said. “I was like, ‘What if they see that red dot and then they don’t go to bat for me?’”

This misconception turns hundreds of viable people away from opting to be organ donors. According to the ATF, the number one priority at any medical institution or hospital is to save lives. Patients are not treated differently if they are organ donors.

In addition, amid all of the excitement surrounding driving, teenagers getting learner’s permits may not expect to think about organ donation. Many may reflexively check “no” without thinking about all the implications.

“Although teens are able to register as organ donors when they get a driver’s license, just 24% of parents of teens ages 15-18 said their child had registered,” Gary Freed, the Mott’s Children’s Hospital’s poll co-director, said.

Organ donation is a life-saving process for so many people, yet many teenagers don’t even recall seeing the option when applying for their permit.

“I didn’t even know you could be an organ donor. I don’t remember seeing a button,” said Luke Peasley, a licensed junior.

For those who do register, many find it to be a way to help save lives when theirs are over.

“I chose to be an organ donor because I don’t care what happens to me once I’m dead. I’d rather my organs be of good use and save someone’s life instead of just sitting in a coffin six feet under,” said Erin Psaila, another licensed junior.

Giampaoli’s experience changed his mindset completely. After finally receiving a transplant, Giampaoli was able to return back to work, get a puppy and continue to watch his kids grow up.

“Everyone knew I had this rare disease and I was on a time clock because the only cure was the transplant. It was stressful because all my family got tested and it turned out that none of them could be a match. Same with a couple of my friends, until a guy I’ve known since I was five years old turned out to be a perfect blood type match. Still, it was probably a good year before we figured out that he could do it,” Giampaoli said. “Once you’ve become a recipient and you see how few organs there are, you become way more receptive.”

Allison Kim, a kidney transplant recipient and middle school teacher at Ralston, views organ donations similarly.

“I think that education definitely would be really useful to save a lot of lives and would give people a chance to at least to just think about the decision,” Kim said.

Kim was only 23 at the time she discovered she had a disease since birth called IgA Nephropathy. Although it doesn’t always lead to kidney failure, in Kim’s case, it did.

“When I was first diagnosed, I was told that in the Bay Area, the wait time for kidneys is around 10 years. I got my first kidney transplant in 2001. I got my second one in January of 2021. This was my second one because kidney transplants don’t last forever,” Kim said.

Even if you are lucky enough to have received a kidney transplant, they typically only last between 10 and 12 years, according to the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. This is why organ donors are essential.

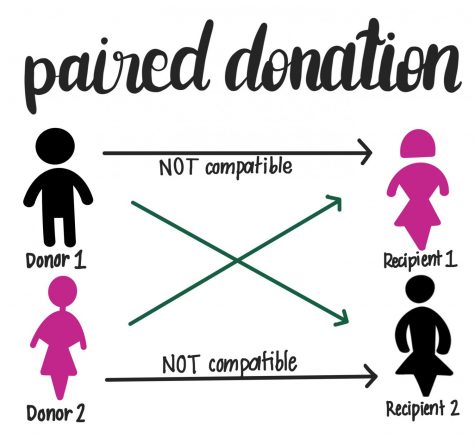

“They have a shelf life. My kidney was 20 years old, which is a pretty good life for a kidney. But eventually, it just kind of gave out. I was really lucky that my sister-in-law stepped forward to donate. However she wasn’t a good match for me, so we did this thing called a paired donation,” Kim said.

Paired donation can occur when there are two donors and two recipients, but the donors don’t match their respective recipients. According to the National Kidney Foundation, “paired donation allows two transplant candidates to receive organs and two donors to give organs though the original recipient/donor pairs were unable to do so with each other.”

Paired donation is one of the processes that allow people to finally receive a transplant and drastically improve their quality of life. Many patients whose kidneys do not work properly must go to a dialysis center multiple times per week and sit there for hours while their kidneys get filtered by a machine while waiting to be eligible for a transplant.

“I was on dialysis for about a year. Dialysis keeps you alive and functional, but you’re not enjoying life. I still was working part-time on it, but it was hard. I didn’t even realize how badly I was feeling until I got a real kidney,” Kim said.

With all the obstacles of getting an organ transplant, the more organ donors there are, the more lives can be saved. That’s where education comes in.

“I think it is important to bring awareness to the topic and get the conversation started,” Ralph Crame, Carlmont’s former principal, said.

Giampaoli and Kim were only two out of the over 100,000 names on the transplant waiting list. While they had family and friends offer to save their lives, many are not as fortunate. More education in schools will lead to more teenagers understanding that the simple task of checking off a box may save a life.

“I would encourage everyone to do it. You can make a huge difference and prevent something that’s obviously very tragic, “ Kim said. “There’s something very beautiful about death being turned into life, which is pretty amazing.”