In the captivating realm of Michelin dining, anonymous assessors traverse the culinary landscape, concealing their identities while holding the ultimate authority over the fate of restaurants and chefs.

The Michelin tire company, founded by the Michelin brothers André and Edouard in France in 1889, entered the culinary world by introducing the Michelin Guide in 1900. This guide aimed to assist early motorists on their travels by providing information on lodging, parking, and repair shops. In 1926, the Guide introduced the concept of Michelin Stars, initially with a single Star, which later expanded to one, two, and three Michelin Stars in 1931, along with established criteria for inspectors.

While it may be surprising that a tire company impacted the culinary world, the Michelin Guide’s influence cannot be underestimated. Its reach is extensive, with over 30 million guides distributed in 24 countries. This underscores the significance of inspector anonymity, adding a mystery to their lifestyles and backgrounds, especially their origins. An anonymous chief inspector* has been with Michelin for about 15 years and is based in the United States.

“I’ve always loved the hospitality industry. I studied it in college and worked in various positions for over 10 years before I became a Michelin inspector. Becoming an inspector was a fantastic opportunity and a step in my career evolution that I had to take, and still to this day, I am so happy I did,” the inspector said.

Notably, many of the inspector’s colleagues also have roots in the hospitality sector.

“We are all former hospitality professionals who are now Michelin employees. We all have at least 10 years of experience, which ensures our precise and technical knowledge of the field. We also received two years of training in the Michelin Guide’s methodology,” the inspector said.

According to the inspector, they dine at upwards of 300 meals annually, both lunch and dinner, from Monday to Friday. Inspector teams are comprised of local and international members of diverse ages and backgrounds, representing over 15 nationalities and speaking 25 languages. They explore the global gastronomic scene to discover the finest talents.

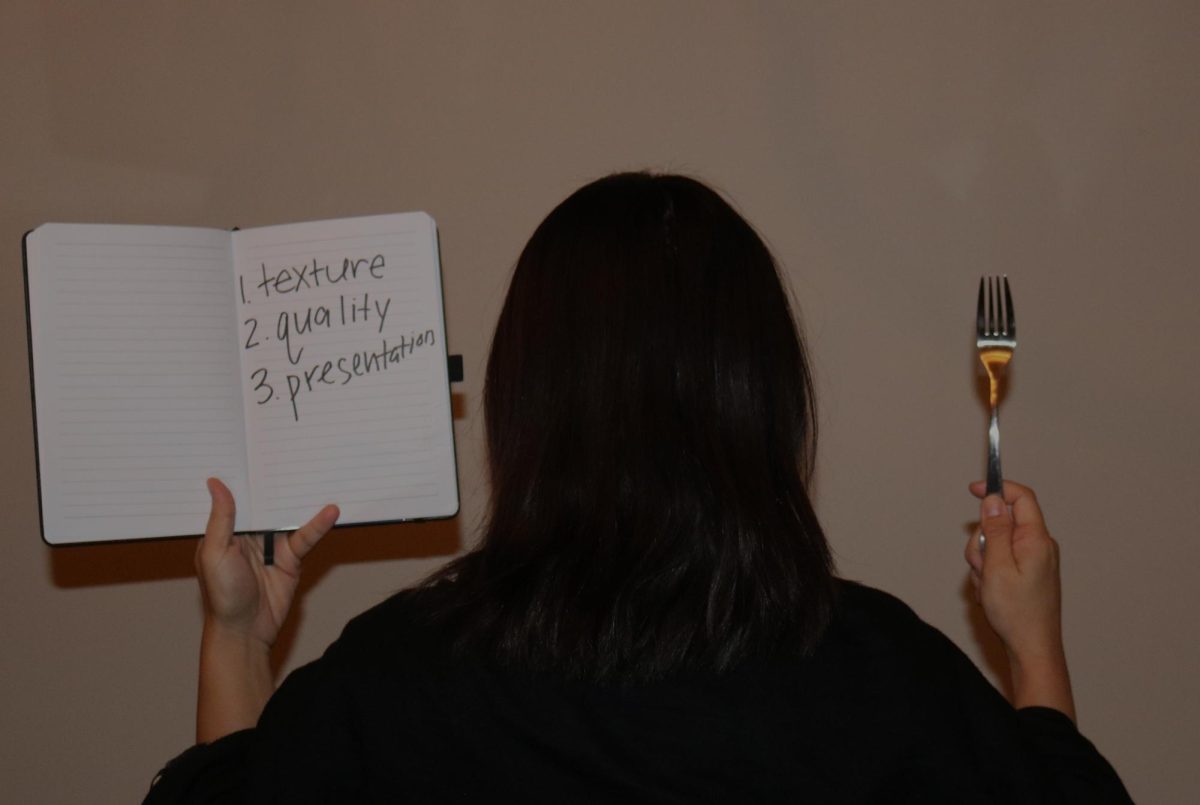

To provide accurate and consistent assessments, inspectors adhere to the Michelin Guide’s universal criteria: 1) quality products; 2) the harmony of flavors; 3) the mastery of cooking techniques; 4) the personality of the chef in the cuisine; and 5) consistency across multiple visits, as each restaurant undergoes several inspections annually.

Although inspectors have guidelines to follow and a job to perform, the inspector asserts that “no one can distinguish a regular customer from a Michelin Guide inspector. Our identity, location during visits, and other details are all kept secret.”

Jayden Chow, a senior at Carlmont High School, has dined at 15 Michelin-star restaurants, ranging from Hong Kong to the Bay Area. Dining habits are quite similar when comparing regular customers to Michelin inspectors.

“Typically, I ask the waiter for recommendations when visiting a restaurant for the first time. Often, there’s a daily special, which I like to try,” Chow said.

The inspector emphasizes the importance of asking questions and frequently seeks recommendations, specialties, or specific dish details.

Regarding Michelin criteria, the inspector’s guidelines differ from what Chow initially observes and values about fine dining establishments. Chow places high importance on ambiance and service, often waiting two to three months for the Michelin restaurant experience.

“The point of going to a Michelin restaurant is mostly for the experience, and for one-star restaurants, you go there for the quality, how well put the dishes are, and the good service. Usually, as the stars go up, fewer people are in the restaurant, and they’re more concentrated on you. Three-star restaurants source ingredients from around the world, and you’ll see something tough to get,” Chow said.

Chow’s opinion differs slightly from the inspector’s focus, which primarily evaluates the cuisine, mentioning service, quality, decor, and experience as extra details. However, the core basis of the Michelin dining critique remains relatively consistent between the customer and inspector.

The inspection criteria are equally vital to chefs within Michelin-rated establishments. Edalyn Garcia, the current head chef at The Village Pub in Woodside, California, has maintained one Michelin star since 2009. The anonymity of inspectors necessitates a high level of quality at the restaurant.

“Every dish has to be consistent because we don’t know when they come. They might’ve come already. I don’t know. It’s all about ensuring that the team is trained properly and trusting that they would execute everything up to standard,” Garcia said.

The possession of a Michelin star can significantly impact a restaurant’s reputation, attracting customers or leading chefs to depart. Garcia previously worked at a starred restaurant but stopped working there soon after they lost their star.

Given the influence Michelin inspectors wield in determining the fate of restaurants and where customers choose to spend their money, it’s unsurprising that they maintain an air of mystique. Nevertheless, they are “just like anyone else and enjoy taking photos of their food.”

*The Chief Inspector is anonymous due to the nature of Michelin inspectors. They test restaurants in anonymity in order to ensure that they do not receive any special treatment which is essential to the creditability of the Michelin Guide.