One thousand one hundred thirty hours. That is how much time the average California student spends at school every year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Out of 6,000 hours spent awake, that is how long students must learn in their respective educational environments every year, no matter how inconsistent the quality of varying schools may be.

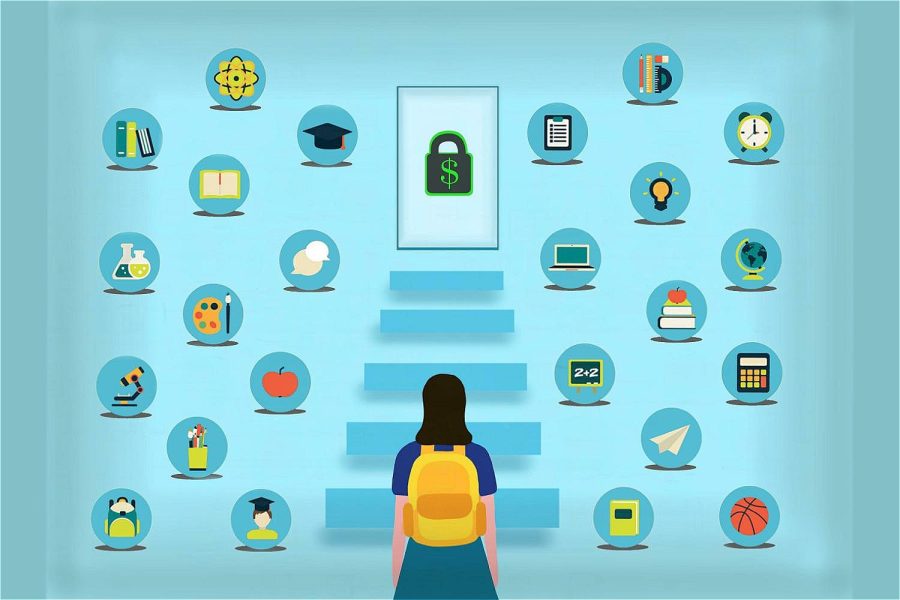

Often, students without financial means don’t have the opportunity to attend a school other than a public one typically assigned to them.

A student’s educational environment, however, can be a significant factor in their learning, influences, and life. It may sometimes determine the difference between succeeding or failing, both academically and socially. Each student’s preferred style of learning, one in which they will thrive, might differ from the next’s.

This is where school choice comes into play for many.

Most people in the United States are generally supportive of school choice. That is, allowing students to attend the schools they want.

However, another aspect of school choice that has sparked questions and debate is the direction of public education funds to a student’s preferred school, whether it be a public, private, charter, home school, or another learning environment.

This includes Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) and school vouchers. ESAs, for example, allow parents to withdraw their children from public district or charter schools and receive public funds in government-authorized savings accounts with various uses, although limited. Those funds can cover private school tuition and fees, online learning programs, private tutoring, community college costs, higher education expenses, and other approved services.

Supporters argue that school choice improves educational outcomes by expanding opportunity and access and allowing parents more control over student learning. On the other hand, most opposers say this takes necessary funding away from the public school system. However, many more factors contribute to the reasoning of both sides.

“The term ‘school choice’ is broad. Historically, families with financial means have exercised choice by moving to districts with high-performing schools or sending their children to private schools. But that leaves many students out. School choice is about removing the link between privilege and access to quality education,” said Chantal Lovell, the vice president of communications of EdChoice.

Micheal Alexander, president and chairman of the Board of Californians for School Choice, agrees that school choice benefits many families that may not be able to afford better educational opportunities.

“Technically, all parents have school choice. All they have to do is sign the check. But what we’re talking about is the access of taxpayers, who happen to be parents, to their own money, collected and spent at government schools so that they can make choices in education. That’s really what school choice is about in the modern era,” Alexander said.

While this may seem good, some argue that significant adverse effects exist. The primary opposers of school choice are often teachers’ unions that advocate for protecting public education funding.

In Arizona, for example, new measures led to over one million K-12 public school students becoming eligible to receive vouchers to fund their attendance at their chosen type of schooling. Teachers unions were quick to strike back, claiming that this weakened public schools, but they ultimately failed to change the new school choice policies.

David Goldberg, the vice president of the California Teachers Association, shares his views that align with those of many opposers of school choice across the country.

“First of all, we support well-funded public education. We do not support the funding of private schools, religious schools, or parochial schools with public money,” Goldberg said. “A lot of times, the way it works with the public funding of private schools is it basically ends up being a subsidy for wealthy people. Because most people want some state subsidies, working people and poor people cannot afford to send their kids to these private schools. This basically leads to this disinvestment in public schools to fund wealthier people’s choices of sending their kids to private schools that are often racially segregated.”

Goldberg emphasizes that public schools already have little funding and that school choice does not lead to better education outcomes for the majority of students, in stark contrast to supporting arguments.

“Public education is already deeply, deeply under-invested in California. We used to be the biggest and the best-funded public education system in the nation but are now far behind. But really there’s no reason for us not to have enough funding for our public system,” Goldberg said.

While it’s true that many believe the public school system should receive more funding, Alexander says that school choice, if executed correctly, would not exacerbate the issue.

Californians for School Choice, led by Alexander, recently attempted to bring an initiative to the ballot this November. The Educational Freedom Act would have created an ESA on behalf of parents for their child’s education, though it did not collect enough signatures.

“The system is opt-in. It won’t take any money away from school districts under our initiative. The school districts will continue to receive the same money as they have. They’ll operate the same way they have been. Nothing in our bill alters the way in which the schools are managed. Anybody who wants out can simply get out, take their money, and go build their own future,” Alexander said.

However, Goldberg sees the promotion of private school choice as usually a direct attempt to degrade the public education profession as well as the public system. Educators already face a great deal of stress and demanding environments, which has also been a significant factor in the current public school teacher shortage across the nation.

“Those people pushing to privatize public education are also those who are, often, but not always, pushing to devalue the public education profession in general. Often, they are hostile or at work to undermine public education unions that actually fight to improve conditions for educators and students. It’s similar not just to public education but also to the privatization of public health or other services, which is often a great source of revenue for corporations. And it’s usually the same with the privatization of prisons, which is tied to the incentive to put more people in prison to make money off them,” Goldberg said.

While many students may want to change schools for more educational opportunities or programs, some people also question if school choice really helps students improve academically.

In recent years, in contrast to older studies, some research has shown that voucher programs in Indiana, Louisiana, Ohio, and Washington, D.C. hurt student achievement, causing declines in test scores.

However, according to Lovell, the test scores don’t tell the whole story.

“There are studies that show some students struggle in the immediate term. But, over time, those students catch up, and their performance improves,” Lovell said. “These findings are similar to other studies that find some students fall behind when they transfer to a new school, but they get settled, catch up, and thrive.”

A study of Milwaukee’s long-running voucher program found that participating students were more likely to graduate high school and attend four-year colleges.

Much evidence, measured by test scores, also suggests that public schools improve in response to competition produced by school voucher programs.

More consistent impacts are illustrated in a recent study in Florida, a state with the nation’s most extensive private school choice program. There, tax credit–funded vouchers led to slight improvements in math and reading test scores as well as suspension and attendance rates. These effects were the most impactful among lower-income students. The study is one of the few that analyzes the outcomes of vouchers based on factors other than test scores.

The controversy surrounding school choice also sometimes touches on a deeper matter, one involving religion. Many opposers, including Goldberg, tend to stress a separation between church and state, meaning that school choice should not be used to fund the tuition of religious private schools.

While this is a legitimate perspective, Lovell believes that, above all, a child should receive an education that meets their needs; this matters more than restricting schools merely because they involve an aspect of religion, which only takes away that option for families who cannot afford it.

“I think it’s really up to families because they are best positioned to understand what their students need. And so they should have the ability to choose a religious school if they want,” Lovell said.

Supporters highlight that school choice yields an important positive outcome for many educational environments by creating competition between varying schools.

“School choice drives competition, so when families are given the option to exercise school choice, we see a positive impact on the surrounding public schools as this competition with other schools encourages public schools to improve student performance as well,” Lovell said.

Often, students utilize school choice to gain new educational opportunities and programs unavailable in their previous school. According to a report by the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), California’s District of Choice program led to a response in which most home districts (where students transferred from) actively improved their instructional offerings, taking steps to learn more about community priorities and develop new academic programs. These home districts also showed better test results over time and a reduction in the number of students wanting to transfer out.

The same report shows that the transfer students had varied demographic backgrounds. Of them, 27% came from low–income families. Additionally, 35% of all students participating in the program were white, 32% were Hispanic or Latino, and 24% were Asian.

“We have children caught in semi-literacy, particularly children of new immigrants, who are not learning what they need to learn,” Alexander said. “Some of the schools are just failures. So we need private competition. Historically, competition produces better educational outcomes. And we know that private schools generally perform better than public schools, all except a few.”

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NEAP) data and other research have shown that private school students score better in almost all subjects than public school students. Although many factors aside from test scores need to be considered, many parents see private schooling as a better environment with, typically, smaller class sizes. Nevertheless, the question remains centered around whether families should even have the opportunity to use public money to select a non-public school that meets their children’s needs.

“So ultimately, what we’re dealing with is a monopoly that government schools have on the use of government funds,” Alexander said. “I support public education. I just don’t support the idea to the extent that you could only access that money at a government school.”

The issue of school choice is complicated, with two sides that have legitimate stances and concerns. Like any controversial matter, perspectives often depend on one’s position. Parents, for instance, are found to be more likely to show support for school choice. School choice can produce beneficial outcomes for some students but could harm others. In the long run, Americans have seen school choice provide new opportunities for the growth of both students and education systems in many cases.

“All students should have the opportunity to thrive in an educational environment that meets their own unique needs and strengths. Just like thinking about funding on a per-pupil basis, our education system should fund students, not systems,” Lovell said.