Exploring the education offered to at-risk and incarcerated American youth

“I lost a friend to senseless violence. I figured no one is born holding a gun. Instead of acting out of anger, I wanted to educate myself on where the failures were — whether they stemmed from the family, the community, or systemic problems,” said Johnny Kovatch, founder of Unlock the Arts, a non-profit organization dedicated to the use of creative expression as a catalyst for personal transformation of system-impacted individuals.

Kovatch had volunteered at three of the juvenile hall facilities in Los Angeles County, Sylmar East Lake Central, and Los Padrinos. At the time, teens were being tried as adults. This was before bills such as Senate Bill (SB) 260 were passed in California to establish a youth offender parole hearing mechanism for youth, so the individuals were doing much state time. Kovatch discovered a clear lack of support.

For many at-risk and incarcerated youth education is more than a right — it’s a path to breaking a cycle of poverty, crime, and marginalization.

The state of education in the system

According to 2003 statistics, 85% of youth in the country’s justice system have difficulty reading and statistics show that approximately 40% of America’s juvenile offenders at a 10th-grade level read below a 4th-grade level.

Since the 2000s, it has not been uncommon for these students to graduate with poor reading skills. Los Angeles County was sued for this reason in 2010 after it was revealed that some youths were given diplomas despite being illiterate. A settlement led to the county implementing reading assessments and intervention programs.

More recent data analyzed the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP), administered when students are in grades 3-8 and again in grade 11. In the best-performing juvenile court school during the 2018-2019 school year, 51.85% of students did not meet the English Language Arts (ELA) standard and 84.62% did not meet the Mathematics standard. During the 2021-2022 school year, 61.54% of students did not meet the ELA standard and 86.49% did not meet the Mathematics standard. In both school years, these percentages far exceeded those of California public school students who did not meet the standard.

“I wish you could see some of the packets that these kids get. I’ve seen curricula that focus on the Russian Revolution when the students don’t even know how to spell. It’s a curriculum that doesn’t make sense,” said Suzanne Campbell, Co-Executive Director of Underground GRIT, an organization that promotes change in prisons, jails, and juvenile institutions and helps incarcerated people with reentry into society.

Campbell, along with others, founded Underground GRIT after recognizing the gaps in the systems of care and seeing long-term youth falling through the cracks. It works with system-impacted youth and adults ranging from ages 12 to the oldest being 69, many of whom have special needs and Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

A 2013 study found that incarcerated special education and general education students exhibited substantial reading deficits in the areas of decoding and reading comprehension. It also found that age, race, and special education status were significant predictors of reading deficits.

Complete education data for incarcerated students is generally difficult to access, in part due to privacy concerns, lacking data entry, and a lack of assessments created for the needs of incarcerated students.

According to a recent study from the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools, many students did not receive the initial reading assessment or follow-up evaluations within the required timeframes. Additionally, the data uncovered unexpected and unexplained patterns in reading ability. Some students showed drastic changes, such as jumping from a second-grade reading level to an 11th grade between assessments that were not very far apart, while others experienced the reverse, suggesting potential flaws in the assessment process or data interpretation.

“There should be more transparency as far as what kind of education these youth are getting. Just like public schools have their supervised testing and all those things, the same thing should happen for education sites for youth that are incarcerated,” Campbell said.

In approaching the issues involving juvenile justice, Campbell considers three ways: prevention, intervention, and reentering the community.

“So in prevention would be the stopping the prison, the school to prison pipeline, where issues of behavior in schools are dealt with as criminal activity when a lot of time there’s underlying problems that should be addressed. And so that interaction with suspensions, expulsions, or police contact when youth are still in school, enter them into the system, and then a lot of times when they’re incarcerated. In juvenile hall, the education they’re provided is below what they should be getting, which is why we need intervention.”

Campbell emphasizes the final piece — reentering the community — is often extremely difficult.

“When youth have been incarcerated, they’re viewed a certain way, and many school districts, traditional school districts, do not want the students returning, so their time served doesn’t matter. They are pushed aside to other alternative sites, sometimes ones not even within the district.”

In Campbell’s area of work, youth become part of the Orange County Department of Education when they are incarcerated. They are then no longer part of their original school districts. There are also particular parts of the Orange County Department of Education that exist outside of juvenile halls. These are called ACCESS (Alternative Education) sites. Other counties may have a similar system.

“A lot of times traditional high schools say, ‘Why don’t those kids go to ACCESS? It’s better for them. They shouldn’t go to a regular high school.’ So for a youth who’s an 11th or 12th grader who wants to return to their high school, it’s very, very difficult because districts will put up these artificial barriers,” Campbell said.

There may be additional logistics problems.

“If a parent cannot be there to get them enrolled, it can take weeks for them to get enrolled, and they risk being violated and going back to juvenile hall just because they can’t get enrolled in school,” Campbell said.

Options for at-risk students

Norbert Demanuel taught for 10 years in Job Corps, a program federally funded by the Department of Labor that gives underserved or at-risk youth an opportunity to earn a high school diploma and a vocational certificate in areas such as carpentry, electrical nursing, or medical assistance. The student population was 16 to 24 years old, consisting of students from the Bay Area, primarily the East Bay.

Demanuel’s role as a math instructor was to prepare his students for the Test of Adult Basic Education (TABE).

“A bigger part of my job was mentoring proper workplace behavior and proper social skills. So these students can not only succeed in my class or in the program, but they can become employable and self reliant. I have to really just mentor proper behavior and coping skills. I have to set basically, expectations and boundaries. I’d say about 90% of the students there had various anger issues, and they don’t know how to cope.”

Instructors of incarcerated and at-risk youth often significantly emphasize the building of interpersonal skills as much as, or more than, a general education.

“There’s a place for both of them. I think social skills are incredibly important, especially if there’s a deficit in that area. However, I think that there’s room for a quality academic curriculum with those other supports. I’m not saying everybody’s got to go to a four-year university. I just think there should be an opportunity for both,” Campbell said.

Demanuel says that many of these students came from very disadvantaged backgrounds.

“Some were involved in gang life, homelessness, and abusive households. Some of them may have been physically abused or sexually abused. Some of them had struggles like drug dependency and alcohol dependency,” Demanuel said.

There is a recruitment team to gather struggling students to enroll in the program, which acts like a scholarship for students, providing necessities like health insurance and food as well as education.

“In my experience, what it means to be at risk is that these students are at risk not to make it in society. This Job Corps program is kind of like their last stop, or it’s going to dictate where their future is going to go. Some of them may go to prison while others get union jobs that can sometimes be life-changing as they get a good salary and union benefits. I’ve had a few students go on to college,” Demanuel said.

On a deeper level, Demanuel has seen patterns with the students he has taught over the years.

“Generational poverty is real. I had a student who told me that his grandfather was in prison and his father was in prison. He himself had some cognitive issues. It’s just saddening to see the cycle going on and on,” Demanuel said.

Creative outlets uncover hidden struggles

“We all want to be loved. But we also all want to be heard,” Kovatch said. “And so I went into juvenile hall facilities with no expectations, just to listen. To listen to their stories and listen to how people were brought up and what was considered normal to them. I decided to start going every single week. Some of these participants had a lot of friends and a lot of relatives. And sometimes a lot of them didn’t even show up for them — no phone calls, no anything. That’s gonna create isolation and the pressure or the need or the desire for validation. Some guys say ‘I didn’t want to be in a gang, but I’m getting noticed. I’m getting love.’”

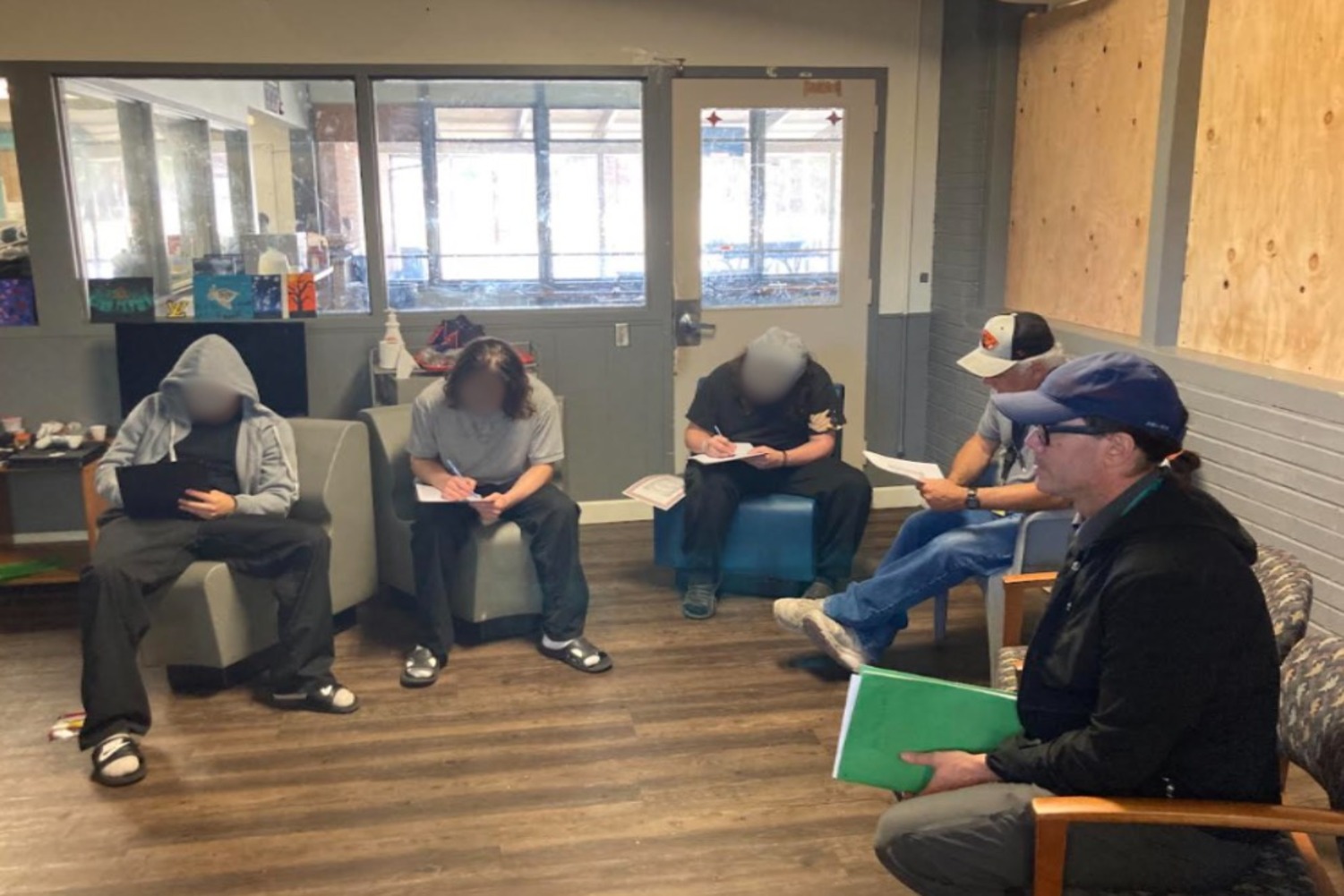

Kovatch is still in the state prisons as he has been for almost 10 years. Seeking to bring the writing program back to teens and our young adults after he moved to Portland, he proposed bringing an expressive writing program to the biggest Youth Authority in Oregon. The program served a dual purpose of improving public safety and these positive outcomes for kids.

“They’re finally able to see that the notebooks we passed out aren’t just lined paper, but they’re mirrors. So it’s an amazing reflection doing that hard look inward that’s needed for the essential personal growth, self-empowerment, self-belief, and self-worth. The biggest difference about what we’re doing is we see it as a kinship, not a class. We remove the pressure to succeed because we want to keep it high energy and low stress and make it as uncomfortable as inviting in a safe space. Some of the topics we cover include adverse childhood experiences and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),” Kovatch said.

Kovatch sees Unlock the Arts, which is funded by foundations that believe in its mission such as the Robert A. Sullivan Family Donor Advised Fund. as a window into a participant’s character because it is not a program mandated for release. Participants give up their free time to choose to be comfortable with being uncomfortable for the right reasons.

“Courage could mean one thing on the streets, but in our circle, it means a whole other thing. Being able to read in front of someone for the first time, being able to even write and actually admit things on the page. Moving away from our speaking voices to our writing voices, we can hit these reflections on a deeper, more intimate level,” Kovatch said.

The program provides an alternative to what used to be a destructive impulse by allowing participants to weave logic and rationale into their expressive writing.

“It’s almost like shaking up a can of soda, and instead of just opening it up, you’re just slowly twisting until all the pressure is gone, and then you’re popping the top. And that’s the power of what we’re doing,” Kovatch said.

Students can obtain a high school diploma, or at least keep working towards it. However, through alternative programs like Unlock the Arts, steadfast support and the opportunity for self-betterment are more thoroughly offered.

“You never graduate from, from self reflection. You always be in a capacity to listen and learn right, without judgment. That’s something that was instilled in me and something we carry on within the program,” Kovatch said.

Breaking cycles

By considering the interconnected elements that make up these kids’ experiences, Kravitch says, we can create a more supportive and effective educational framework that not only helps these youth succeed academically but also empowers them to break free from cycles of poverty and crime.

“If someone is putting in the work, it’s going to be recognized and earned because they are doing it for the right reasons. They’re engaging in the necessary internal reflection, addressing the underlying factors that contributed to their actions. This doesn’t excuse their behavior, but it provides context for understanding where they strayed from the path and why. Now they can course-correct and reset their trajectory, equipped with the tools to do this self-reflection and learning,” Kravitch said.