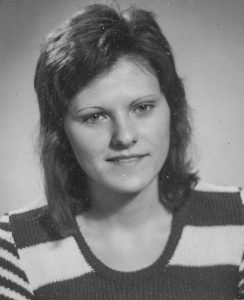

From humble origins to Nobel acclaim: Kati Karikó’s ascent to scientific stardom

There once was a small, curious girl who lived in the little village of Kisújszállás, Hungary. What would appear to be a mundane pattern of nature to any passerby was the most captivating thing in the world to this girl. Today, that little girl has grown up to overcome countless hardships, eventually becoming a decorated scientist whose contributions have saved millions of lives.

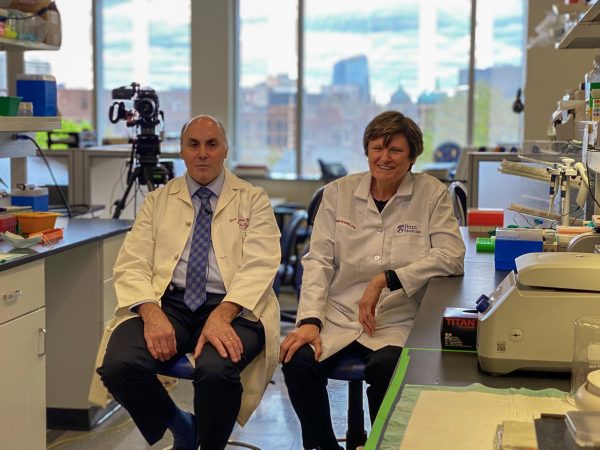

Dr. Katalin Karikó is a Hungarian-born biochemist whose work in messenger RNA (mRNA) with American immunologist Dr. Drew Weissman became the foundation for the COVID-19 vaccine. Because of the novelty and impact of their research, Karikó and Weissman were awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

“When I first found out, my worry was that now I have to get a long dress and coat. Everything in my mind was spinning. It was just unbelievable,” Karikó said.

However, Karikó’s journey to scientific stardom was not a smooth one. Despite facing setback after setback, her dedication to the scientific field never wavered, and it is this passion and perseverance that makes her story a truly remarkable one.

In a Hungarian family’s backyard, a chick breaks out of its eggshell. Nearby, a young girl quietly observes.

“When I was growing up, my family had a big yard with a garden and animals — there was nature everywhere. I would look at the plants and our family chickens, and I would notice how chicks come out from their eggs. As a child, I was interested in understanding how all of this could happen, and I think every child is like that. They are curious,” Karikó said.

The daughter of a butcher, Karikó attributes her passion for science to her childhood environment. At the time, Kisújszállás was a rural area with only a few paved streets; nature was everywhere the eye could see, from sprawling grasslands to great plains. Karikó spent her childhood in a small house made of clay and straw, roofed with a thick layer of reeds.

Fascinated by her natural surroundings, Karikó became more invested in science and showed an innate prowess for the subject.

“In elementary school, I was already competing in biology competitions, and they were all about knowing facts about the body, nature, and other things. In eighth grade, I was the third best in the country,” Karikó said.

Not many of Karikó’s peers understood her interest in science. However, Karikó sees the value in respecting the interests of others, regardless of how strange they may seem.

Karikó’s parents were also adamant about their daughter receiving an enriching education. Attending school allowed Karikó to meet numerous adults and peers who would influence her as she grew up.

“You have your teachers, parents, and friends who shape what kind of person you will become. So it’s important that teachers nurture your curiosity,” Karikó said.

Upon entering high school, Karikó met two teachers who would change her life. The words of both teachers would leave a lasting mark on Karikó as she matured.

“From day one, I had a teacher in high school who did not like me — he hated me. He told me that it was very difficult to get into university, and he said, ‘I will make sure that you will not get into a university.’ This was a very stressful message; how was I supposed to find the silver lining in this?” Karikó said.

Instead of becoming dejected, as one might expect, Karikó took her teacher’s threats as fuel to continue persevering. Looking back on this experience, she realizes how important it was for her younger self to have an antagonistic figure in her life to challenge her.

“If he had told me instead, ‘I know somebody in that college; I’ll make sure that you get in,’ then I would have spent my summer sitting back. But because he told me the opposite, it made me work much harder,” Karikó said.

However, at the same high school, Karikó met a teacher who was incredibly supportive of her. This teacher had faith in her and believed in her. And that belief went a long way.

“Everyone needs a cheerleader in their life — someone who is there for you when you are questioning yourself. This teacher was my cheerleader,” Karikó said.

She attributes much of her aspirations as an adolescent to this teacher, who convinced her that she could accomplish great things.

“That teacher, despite knowing that my father had a sixth grade education and my mother had an eighth grade education, told me that I could be a scientist before I even knew what a scientist really did. I couldn’t even imagine it at that time, but you need somebody who believes in you so much that you finally believe in yourself, too,” Karikó said.

So what might one take away from this tale of two teachers?

“Whether you have a good teacher or a bad one, you always have to take from their words the message that will improve you and make you better,” Karikó said.

Karikó’s first experience in a laboratory occurred when she was a university student.

“I went to work in the laboratory because I wanted to see what was going on there. And the head of the lab told me, ‘You can spend the rest of your life in the laboratory. Go and spend your summer in a fishery institute and collect fish fat and then come back and we’ll measure it.’ So I started off in the lipid team where we would analyze fats,” Karikó said.

In the same lab, there was another team whose research would inspire Karikó to pursue gene therapy, which is a field that works to manipulate gene expression for therapeutic use.

“There was another team that put DNA into the fat and delivered it to the cell. And that was my first time observing gene therapy; we could see the protein that resulted from the DNA we coded for,” Karikó said.

Fast forward to 1978, and Karikó had graduated to start lab work involving RNA synthesis. At 23 years old, she was synthesizing short strands of RNA, unknowingly setting the stage for her transition to mRNA research.

After 11 years had passed, Karikó arrived at the University of Pennsylvania. She had developed an intense interest in mRNA and gene therapy, a topic that many believed was not worth the effort and had no potential for growth.

“When I told people that I work with mRNA, they felt sorry for me because they knew how difficult it was, but I fell in love with it,” Karikó said.

Choosing to ignore the opinions of others, she continued to pursue this research area.

“Once you find something that interests you, you’ll delve deeper because you want to learn more about it. As long as they get knowledge, anything can be interesting. The most someone else might say is, ‘Oh my god, who cares about that?’ But if you gain knowledge and you become good at something, then you’ll enjoy it,” Karikó said.

Three million deaths. Eighteen million hospitalizations. One hundred twenty million COVID-19 infections. All prevented by the genesis of mRNA vaccines.

The Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine is the first mRNA vaccine to receive full Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for emergency use in the United States.

Pfizer and Moderna, names that shot to distinction during the COVID-19 pandemic, are two biotechnology companies that manufactured the widely distributed mRNA vaccines. Karikó and Weissman, names that remain widely unheard of among the non-scientific community, are two scientists who created the mRNA technology behind the COVID-19 vaccine.

“I had the methods, peptides, proteins, viruses, and DNA involved in making the vaccine, but I didn’t have the RNA. Then, I met Kati Karikó, who was working on RNA, and we started working together,” Weissman said.

However, it’s important to note that Karikó and Weissman were not the first to conduct research on mRNA. The molecule was first discovered in the 1960s, and research was conducted on how mRNA could be delivered into cells in the 1970s.

“The development of medical treatments — in this instance, the development of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines — is a long arduous process, a fruit of many, many contributions by many, many scientists,” said Dr. Eli Gilboa, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Miami. Gilboa is renowned for his pioneering work in gene therapy; he and his team of researchers were involved in the creation of mRNA-transfected dendritic cell (DC) vaccines, which are seen as the forerunner of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines.

When Karikó and Weissman first started working together, they had disparate scientific backgrounds, but rather than letting that hinder them, they took that to their mutual advantage.

“We worked together for 26 years. In the beginning, it was stimulating because we had very different knowledge bases. I was an immunologist, and Kati was a molecular biologist. I taught her about immunology, she taught me about making RNA and its applications. So it was a lot of learning,” Weissman said.

As the two researchers grew more accustomed to each other, they adopted their own team dynamic.

“From there, it became us constantly bouncing ideas off of each other, evaluating data to determine what it meant, and talking about what we had to do next,” Weissman said.

And this went on for decades, until finally, Karikó and Weissman discovered what would become the foundation for the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The impact of their work earned them the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

“It was an ultimate recognition and triumph of basic science that I find increasingly sidelined by ‘big’ and ‘safe’ science. It doesn’t happen often, and it was not an easy journey, especially for Dr. Karikó,” Gilboa said.

“I never wanted to leave Hungary,” Karikó said.

After all, Hungary was the home of her childhood. However, after running out of money in Hungary, Karikó and her family made the decision to immigrate to the U.S., but the move was anything but easy for Karikó.

“When we came to America in 1985, we didn’t have credit cards or cell phones. I didn’t have relatives or an old classmate or a teacher who could’ve helped me; it was only my husband and my two-year-old daughter. When we moved, I just felt like I didn’t have anyone,” Karikó said.

In addition to the lack of a support system in America, Karikó also dealt with challenges in the workforce as an immigrant.

“I have a pretty strong accent. When I was 18 years old, I couldn’t speak a word of English; everything I learned, I had learned in Russian. So after coming to America, a lot of people who’ve heard my accent thought that I wasn’t smart,” Karikó said.

When she proved herself more than capable as a scientist and started working at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikó’s passion project received little funding from the institution.

“I had no money, no technicians, no students, nothing. I did all of those experiments with my own hands. It forced me to be better, and looking back, I realize how much this experience improved me,” Karikó said.

During the formative years of Karikó and Weissman’s mRNA research, Karikó was given an ultimatum from the University of Pennsylvania: either take a demotion or give up on her mRNA research. She believes this was because her research was not bringing in enough money for the college.

“For me, it was not like I started somewhere low and then got promoted and my life started getting better from there. I didn’t travel on a straight path from the bottom of the mountain to the peak. I started at the bottom, got demoted, then terminated — I just kept going down, until finally, I went into forced retirement,” Karikó said.

At the time, Karikó chose to be demoted because of her strong desire to continue her research. Although discouraged, she did not let it affect her passion for science.

“I wouldn’t be here if I hadn’t been terminated in my position several times. What I emphasize from this is that when somebody is making a decision about you, telling you to get out, don’t start to feel sorry for yourself or blame somebody else. Don’t start to compare yourself to others, saying this person is worse than me so why was I removed and not them,” Karikó said.

Instead of dwelling on the disappointment, Karikó decided to move on and focus on the future.

“What you have to do is not waste time on what you cannot change. If you are fired, then you’re fired. And all of that energy, all of that attention, needs to be focused on what’s next. You have to focus on what you can change,” Karikó said.

She believes that the challenges and obstacles she faced were all learning experiences meant to help her grow. Although recounting those challenges dredges up some unpleasant memories, ultimately, Karikó believes she would not be who she is today without those experiences.

“That’s why, when I get an award, I say thank you to all the people who tried to make my life miserable. Because they made me work harder. They made me want to improve myself. I told myself that I had to study, I had to be the best. I was forced to be the best by the people who were rooting against me,” Karikó said. “And that’s what you have to focus on: your own self-improvement. Always.”

Despite the injustices Karikó faced, she always made sure to support other aspiring scientists. Anna Blakney, who is an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia in the Michael Smith labs, was one of those scientists.

“Something I genuinely admire about Kati is how she’s really good about lifting others up,” Blakney said. “When I was just a postdoc, Kati was the first person that ever invited me to speak at a conference. Often people will only invite faculty to speak at these conferences, but she kept an eye on the literature and had seen a lot of my papers, and so she invited me to talk. That gesture meant a lot to me.”

Karikó’s story also serves as a source of inspiration for young girls who want to pursue science. Both indirectly and directly, she has managed to touch the lives of countless aspiring scientists.

“For so many people, seeing is believing. Being able to see that you can have such a successful scientist who is an immigrant woman in real life? It opens people’s minds to the possibility that they can do it, too,” Blakney said.

But behind the awards, the acclaim, and the tales that have been woven about her story lies that same curious girl from a little village in Hungary, crouching in the grass, waiting patiently for a chick to hatch.

“Forty years ago, I was this curious, observant girl. Now, I’m 68 years old, but I’m still the same. Decade after decade, experiment after experiment, mistake after mistake, I never lost my love for science. And to me, that is the most beautiful thing of all,” Karikó said.