Inside the world of college sports recruiting

High school athletes dream big — envisioning stadiums packed full of cheering fans that follow the thrill of collegiate sports.

Data provided by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) shows that over 8 million students participated in high school sports during the 2023-24 school year.

Many of these 8 million will end their athletic careers after high school, moving on to new phases of their lives.

For some though, sports are more than just a fun extracurricular activity. Demanding a blend of passion and hard work, the road to the next level is a steep climb, but ultimately a worthwhile one. No matter the sport, the journey is deeply challenging. From early-morning training to late-night study sessions, all aspiring student-athletes share a common drive as they work to balance their dreams of playing in college with the realities of day-to-day life.

For student-athletes trying to progress to the next level, effective time management is not an option, it’s a requirement. According to the NCAA, only 6.4% of high school athletes make it to the Division I, II, or III levels overall.

Every hour spent practicing, networking, and on schoolwork matters. As training, games, and recruitment clash with academics, a rigorous system must be created, leaving little room for error. One example is Carlmont senior and Dartmouth diving commit Adam Man. Not only does time spent playing the sport interfere with school, but so does the actual recruiting process. Receiving multiple offers, choosing which school to commit to was a time-consuming effort in itself.

“Visiting the schools was difficult because it was pretty long. I had to fly out to the East Coast and schedule the trips together, skipping all that school and then having to make up tests and explain it to my teachers. Just kind of time managing and balancing everything,” Man said.

A study conducted by PBS found that 66% of Division I athletes in the Pac-12 conference reported that the most challenging part of being an athlete was the lack of free time, with 54% of athletes saying they didn’t have enough time to study for tests. 71% of student-athletes also said that their time commitments prevent them from getting enough sleep, affecting both their academic and athletic performances.

For high school athletes, the time commitments are not as intense, but many echo the same sentiments, as the dedication required to compete for a spot on a college roster often leaves them feeling as if there just aren’t enough hours in a day.

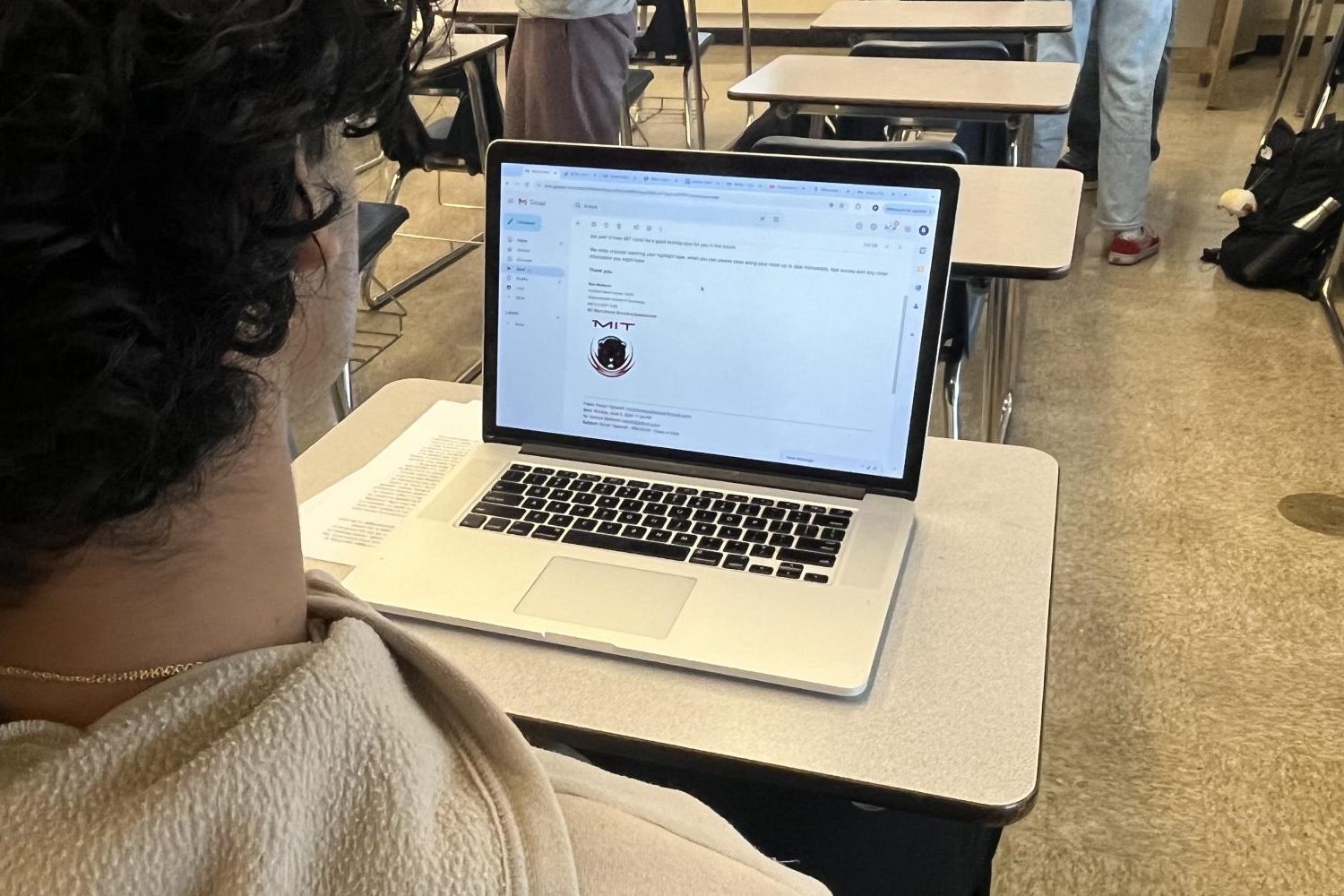

Carlmont junior Rohan Yadavalli juggles school and soccer, all while attracting interest from high-profile schools such as Caltech and MIT.

“In my case, it’s mandatory that I keep my academics up because I’m talking to academically rigorous schools. So even though I train four times a week, I still need to do things like take a lot of AP classes and study for the SAT to make sure that I’m eligible to play,” Yadavalli said.

Carefully managing his schedule, Yadavalli begins his days at 6:30 a.m. and often ends them with late-night study sessions, not sleeping until midnight.

“I’ll stay up late studying after practice, or sometimes I’ll have to skip practice and study for a test for a harder class, like AP Physics,” Yadavalli said.

With Yadavalli having to take the train to practice, he makes clever compromises to fulfill his overlapping responsibilities.

“When I have to take multiple-hour drives to play or when I’m on the train, I spend a lot of that time doing homework and getting my other commitments out of the way so that I can focus on performing at my best,” Yadavalli said.

Likewise, to help him train effectively, Zach Luzzo, a senior at Carlmont committed to St. Olaf for baseball, created a plan for himself to get schoolwork done before doing anything else.

“When I’m working out, I don’t want a thought in the back of my head that ‘oh, I have to turn in this homework assignment,’ so I like to get all my work done for the week, and then I can go about my business working out and getting rest,” Luzzo said.

Recruitment is anything but a passive process. Athletes must leverage any opportunity to draw attention from college coaches who are looking at thousands of athletes every year. For many, this means joining a high-level club team outside of school sports.

Being a part of Stanford Diving Club helped Man a lot, since the club’s main goal was to help him and his teammates get recruited.

“We have a lot of networking connections here, but everyone was in on it, just emailing coaches, and a lot of my coaches already knew some college coaches personally, so they put in good words about us. We had a pretty big class for 2025, seven kids or so, and we’d all share news with each other, and just help each other out,” Man said.

In many cases, solely high school sports aren’t enough for an athlete to get on the radar of colleges. Club teams can provide more exposure, as well as connections to different schools. This holds true for former Fairfield Division I soccer coach Rich Williams, who wouldn’t attend many high school games.

“It would be rare that I would go to a high school game. I would say 95% of my recruiting was from clubs,” Williams said.

Instead, high-level club games made up a large portion of Williams’ scouting.

“When I was doing it, the MLS NEXT league or the Development Academy was just coming to fruition, so that was an easy place to go and scout players on a weekend. So if I was local, I could just look up the MLS next schedules or a National Premier League (NPL) schedule and go watch some teams that I knew had local players,” Williams said.

Being relentless in contacting coaches and showing interest is also extremely important, both for the player and the school they’re contacting.

“You can go after players that you know are interested in your school, that’s a good starting point. By them filling out a recruiting questionnaire, coming to a camp, sending an email or making a call, then that goes on your list of kids who want to come to your school,” Williams said.

Reaching out and building relationships with coaches is essential for anyone looking to make it. Athletes need to push their names out in order to be recognized, and especially in the modern age, an online presence is mandatory. Coaches need a way to quickly assess players’ skill sets to determine whether they have the potential to play. According to the University of Iowa, 85% of Division I, II, and III coaches across 19 sports reported using online platforms to research recruits.

To showcase their highlights, Yadavalli and Man both made YouTube channels where they uploaded footage of them competing, while Luzzo mainly used Twitter to advertise himself and contact coaches.

“I posted a bunch on Twitter. Twitter helped a lot since you can DM coaches,” Luzzo said.

In an analysis of over 5.5 million tweets using machine learning, the University of Iowa also found that being active on Twitter significantly increased the likelihood of an athlete receiving an offer. Self-promotion tweets, such as sharing accomplishments, correlated with a 35% increase in chances of receiving an offer. Ingratiation tweets, tweets complimenting fellow athletes or coaches, were slightly less impactful but still important, correlating with a 21% increase.

In combination with online contact, attending showcases and camps in person is a huge factor for athletes looking to get recruited.

“I would say reaching out online and showcases in person are equally important. If you’re doing a showcase, make sure to reach out to them and introduce yourself, and that lets them put a name to a face and be like, ‘This guy emailed me before the showcase; I’ll look out for him and see how he does,’” Luzzo said.

The main benefit of showcases for players is that they get to meet and impress coaches face-to-face, potentially raising further interest.

“When I was at Surf Cup, I got the opportunity to meet the Caltech coach in person. He said he really enjoyed meeting me and watching me play and wanted to stay in contact so we could set up a camp or a campus tour,” Yadavalli said.

In-person events are also beneficial for coaches looking to narrow down their list of players. Compared to online highlight reels, coaches can see how a player performs throughout the course of a game, including things like their attitude and work ethic, not just their best moments.

“You’re looking for impact players that can immediately help you win, and then you’re also looking for players that can improve the squad,” Williams said, “You kind of have to wade your way through all the people who are interested, so you go watch them play or invite them to a camp to get a read on whether they can play at that level or not.”

Oftentimes, the first deciding factor for whether college coaches will consider an athlete is their grades. No matter how good an athlete is, they must meet the minimum NCAA academic requirements to be eligible for Division I and II sports. This includes completing 16 core classes with a minimum of a 2.3 GPA for Division I, and a 2.2 GPA for Division II.

“A lot of schools with high or decent academics, you need to be able to get into the school, first and foremost. So if you’re an Ivy League school, for example, that probably cuts down your potential recruits by like, 95% so that would be probably the beginning,” Williams said.

Athletes recognize the importance of getting good grades as well. For example, Yadavalli maintains rigorous academic achievement for the potential of attending a top academic school.

“Even if I get a soccer offer, I still need to be able to academically keep up, so it’s not an option for me to slack off at school,” Yadavalli said.

Similarly, Luzzo felt the reward of staying on top of his academics after being told by coaches at a showcase that he was lucky to have had the grades to be considered, and that many candidates had already been eliminated because they didn’t.

“I think grades are the most important thing,” Luzzo said. “The first thing coaches are going to look at is whether they have the grades. And if they do, they’ll look at them. If they don’t it’s an automatic cross-off.”

The NCAA doesn’t set academic requirements for Division III schools. Instead, with most Division III schools being more academically focused, athletes must meet the school’s regular admission standards. In most cases, this is higher than the NCAA Division I and II requirements, meaning academics are typically even more important for athletes aiming to play Division III.

Going even further, Division III schools aren’t allowed to offer athletic scholarships. To get around this rule, many schools offer academic scholarships to athletes as an alternative way to give them money, but their grades must be high enough to receive one. St. Olaf, a Division III school, gave one of these scholarships to Luzzo.

“For St. Olaf, they technically gave me an academic scholarship. They first gave me an offer, and then based on how good my grades were, they could raise the scholarship. So I would get some more money for fees like housing and stuff,” Luzzo said.

Recruiting also comes with a lot of stress. According to a study published under Open Medical Publishing, a peer-reviewed journal, 91% of high school athletes experience some level of stress due to their sport. For those actively seeking to be recruited, these negative emotions can be extremely impactful, and they must find a way to deal with them effectively.

“It’s stressful because there’s always a pressure to perform during games,” Yadavali said.

Yadavali chooses to pray each game before kickoff as a way to manage the pressure and play well. Praying helps him calm himself and allows him to focus on his individual attitude and effort rather than outside influences.

Similarly, Man also dealt with a lot of stress throughout the recruiting process.

“It was definitely a lot, just with school, and especially junior year, with the APs and honors classes stacking up on top of recruiting, it was a whole new level of stress. I went into a little bit of a recruiting slump where I was just done with it, and I didn’t want to do it anymore, but I pushed through,” Man said.

Being able to have other people who were going through the same process as him helped Man a lot, and a support system of family and friends, as well as fellow divers, was particularly important to him.

“Definitely having my teammates, and I was filling them in on stuff that I was going through. That definitely did help with that support system,” Man said. “I think just taking it one step at a time because it can be a lot in perspective. I think just honing in on every single text I sent or update was pretty helpful for me.”

Reaching the next level is a rare and impressive accomplishment, but worth every hour invested for those who make it. Whether they’re focusing on their education or aiming to go pro, collegiate athletes set themselves up for future success while continuing to play the sport they love.

The University of Georgia found that 38% of female big corporation CEOs played intercollegiate sports and that CEOs had 12 times the likelihood of having played intercollegiate sports than the average student. Many stated that the skills developed in competitive sports such as teamwork, leadership, and discipline benefited them in the corporate world.

For some athletes, such as Luzzo, the main objective is to continue playing their sport while getting opportunities to further their education.

“The main goal was to play, but I think the scholarship also was nice to have because it’s always nice to get a less expensive education,” Luzzo said.

For others, such as Yadavalli, getting a good education is the top priority, and sports are mainly just a tool to help them receive one.

“I’d say the hardest part is making sure that I stay motivated. Sometimes you have to travel far to go play a showcase or something like that, so it’s a little bit expensive as well, but it’s definitely worth it because of the possibility of getting scholarship money and going to a good school,” Yadavalli said.

Having access to a wider range of schools and choosing an enjoyable environment is also important, as sports often provide opportunities to athletes that they may not have had otherwise.

“I visited three schools, the University of Pennsylvania, Brown, and Dartmouth. I just noticed that Dartmouth was kind of like the community I felt at Carlmont,” Man said. “Just meeting the team and everything was how I really fell in love with Dartmouth.”

No matter the motivation, the journey to collegiate athletics is one of consistency and discipline, being able to persevere even when things go downhill. High school athletes with goals of playing at the collegiate level must be ready to embark on the twisting and winding recruiting process, all while navigating through life along the way.

“I was pretty stressed out, just the uncertainty of everything,” Man said. “But overall, everything worked out, so I’m really grateful for that.”