“Excuse me. Hi, I just wanted to let you know that I am not going to smile, act dumb, hide my body, pretend, lie, be silent for you. And that everything I do, I do for me, and I’m not going to let you laugh at me, make fun of me, harass me, abuse me or rape me anymore. Because I am a girl and me and my girlfriends are not afraid of you.”

The scribbled, furious words finally unleashed from the brain of a girl, fed up with it all. The anger and exhaustion of young women are what created the riot grrrl movement in the 1990s, a loud, unabashed subculture of feminist-oriented punk rock.

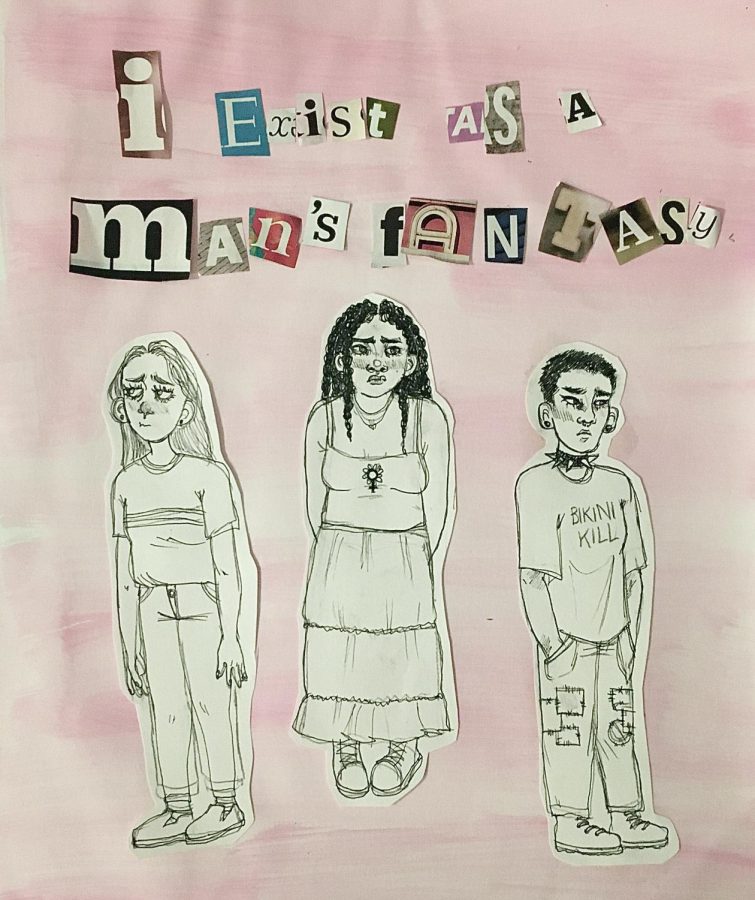

Within the riot grrrl scenes, young women created punk with political lyrics and often shared DIY zines full of their frustrations with sexism. The girls developed a community intended to form a unity between women everywhere to fight misogyny and patriarchy.

The riot grrrl movement introduced the discussion that would spearhead third-wave feminism, the current state of feminist struggle in the United States. They primarily focused on the idea of a united girl revolution, where women support one another and repel self-hatred and the urge to isolate themselves.

“Burn down the walls that say you can’t… Recognize empathy and vulnerability as positive forms of strength. Resist the internalization of capitalism, the reducing of people & oneself to commodities meant to be consumed… Don’t allow the world to make you into a bitter abusive a******… Don’t judge other people. Learn to love yourself,” wrote Kathleen Hanna, the frontwoman of leading riot grrrl band Bikini Kill, in her 1991 zine of the same name.

“Acknowledge emotional violence as real. Figure out how the idea of competition fits into your intimate relationships… Believe people when they tell you they are hurting or are in pain… Close your mind to the propaganda of the status quo by examining its effects on you, cell by artificial cell. Trust.”

It is evident that the modern state of corporate feminism has appropriated feminist ideals for the sake of profit; the authentic anger of young women has been commodified. Hanna and her bandmates Tobi Vail and Kathi Wilcox coined the term “Girl Power,” which has become a vapid slogan for performative activism in the past two decades. Although riot grrrl mostly died out in the mainstream in the mid to late 2000s, its core messages continue to inspire zine creators and bands today.

“This zine exists so grrrls can feel seen & understood,” wrote Samantha Simmons in the first issue of her 2020 zine titled “This Is Not a Test.” “Because our most dangerous weapon is our realization that we aren’t alone.”

Riot grrrl’s emphasis on solidarity between women sparked the conversation that 3rd wave feminism orbits around: internalized misogyny, the inner monologues of sexism that causes women to isolate themselves from one another in a subconscious or conscious desire to satisfy the patriarchal standards set for them.

As in any system of oppression, the oppressed party will often internalize the beliefs that scrutinize them. They will continue to see those things as bad, hate them about themselves, and express that hatred to other people.

“According to Spengler (2014), internalized misogyny is made up of two main elements: self-objectification and passive acceptance,” wrote Utah State University student Audrianna Dehlin in her thesis, “Young Women’s Sexist Beliefs and Internalized Misogyny: Links with Psychosocial and Relational Functioning and Sociopolitical Behavior” (2018).

She continued: “Analysis of this data involves intensive coding based on themes like competitive commentary, self-objectification, expressions of helplessness, remarks about observance of traditional gender roles, and placing males as a top priority.”

Internalized misogyny is more commonly linked to an abundance of physical negative outcomes, including identity foreclosure, psychological distress, disordered eating, and mental illness.

Young women, especially high school- and middle school-aged girls, frequently struggle with these manifestations of internalized sexism. Recently, what has been drawn to the teen consciousness by way of social media is the caricature of the “pick-me” girl.

“The ‘pick me’ archetype is a product of internalized misogyny — hatred, dislike or mistrust of women.” wrote Sarah Gudenau, an Oakland University student. “Misogyny is internalized when women or men subconsciously absorb sexist beliefs through socialization, which is then projected onto oneself or others.”

The “pick-me” girl stereotype is said to want to be the ideal woman: objectifying herself, belittling herself, insulting herself. She flaunts a belief in the nuclear family, the belief that women aren’t funny, that women are objects. The stereotype originates from the idea that a woman can be “one of the good ones.” The “pick-me” girl pours her energy into being the patriarch’s perfect pet, and she will never achieve it.

“Even today, men are seen as superior,” said Carlmont sophomore Luiza Nunes. “And if you get their approval, it can feel like you’re on the same level as them, you’re as cool as them, or you’re as funny and strong.”

A main goal of feminism, especially in its third-wave, is to help girls realize that no matter how hard they try, they will not live up to the patriarchal female standards because they’re impossible to accomplish.

A misconception about the ‘Pick Me’ girl and about internalized misogyny, in general, is that girls act differently in front of men because they are attracted to them and want their attraction reciprocated.

However, in all oppressed populations exist those who actively seek their oppressors’ validation to cope with their dehumanization.

Under the specific lens of patriarchy, the “pick-me” mentality is an often subconscious attempt to lift oneself from the default role of second-class citizenship that women are assigned because of their gender.

It aims to gain power, not to gain attention.

“Us grrrls will never be able to achieve the standards patriarchal society sets for us, and why should we?” wrote 16-year-old Maddy in issue six of her 2020 zine Loudmouth. “It’s so much better if we set our OWN standards, where everyone can feel good and free and safe and accepted.”

Internalized misogyny and its effects are the roots of patriarchal pressure on men and boys, known as toxic masculinity. Psychologist Terry Kupers defines toxic masculinity as involving “the need to aggressively compete and dominate others” and as “the constellation of socially regressive male traits that serve to foster domination, the devaluation of women, homophobia and wanton violence.”

Misogyny perpetrated by boys towards each other is caused by a conscious or a subconscious hatred of anything perceived as feminine. In recent years, these internally sexist beliefs that exist due to socialization have been fortified by the online fear campaigns of the alt-right pipeline.

“Misogyny is used predominantly as the first outreach mechanism,” Ashley Mattheis, a researcher at the University of North Carolina who studies the far right online, told Helen Lewis, a staff writer on The Atlantic. “You were owed something, or your life should have been X, but because of the ridiculous things feminists are doing, you can’t access them.”

The years leading up to and immediately following the 2016 presidential election saw the heyday of anti-feminist, reactionary content on public platforms such as Reddit and YouTube. The caricature of “crazy feminist” is nothing new, but the latest version served to indoctrinate young men and boys into the far-right. These boys are young enough or disinterested enough never to have engaged with political discourse before, providing a clean slate for the alt-right to corrupt. Anti-feminism is typically the starting point.

“In 2016, I was like, quote, ‘one of the boys,’ and that’s because of the friend groups I was hanging out with, in-person and online,” said Carlmont sophomore Ian Lang.

Lang’s opinions on feminism have changed since then. “So I just didn’t know a lot of other perspectives. I didn’t understand either side; I just went along with what I was told.”

Most reactionaries accessed large audiences of preteen and teenage boys through gaming. Gaming communities soon became overrun with bigotry. An extreme example includes the 2b2t anarchy server in Minecraft, where no server regulations allowed a large community of neo-Nazis and alt-right gamers to thrive.

“In certain games like Call of Duty, especially after a round is finished,” Lang said, “you can talk to everyone in the lobby and every- like, especially in certain game modes, you’ll hear racial slurs, everything. Anything you could think of, some person’s probably said. It’s happened to me as well, even if I’m not saying anything. I still get called slurs all the time.”

Online, and even more specifically, in the gaming community, your identity can be hidden. No one knows you, and you don’t know them, which can be a perfect spot to release any and all aggression without consequences.

“It can get really bad, especially over the internet, because over the internet, you can pretty much say anything, and no backlash will come to you,” said Dylan Wong, a sophomore at Carlmont. “Especially while playing games, it’s horrible, I’ll just be in a game and a girl talks, and then it’s just instant, straight-up insults.”

Although “anti-social justice warrior (SJW)” and reactionary content is past its peak, the era had its long-term effects on the overall mentality of gaming communities online. Sexism, racism, and homophobia run rampant, and YouTube continues to promote reactionaries on the recommended page.

Anti-feminist reactionaries access the internal sexism that preexists in their targets and expand upon them through fear tactics. Pick-me girls unlock their internalized misogyny and self-hatred and succumb to them in an effort to survive.

“At young ages, we are given our first experiences in society, and I think it has a big effect on us when we grow into adults,” said Maria Smith*. Smith’s name has been changed in compliance with Carlmont Media’s anonymous sourcing policy. “I saw this experiment where kindergarteners were given options of drawings of kids of different colors, and the interviewers would ask them stereotypical questions inferring the different races. The experiment showed that we begin to develop stereotypes at very young ages. I think this could play a possible role in internalized misogyny.”

She continued, “You don’t have to be a full-grown adult to realize everyone that has been in office has been a man, or how the richest people in the world are men and how everything around us, even in this modern society, is based on the gender you are to some extent.”

These more seemingly extreme examples of giving into status-quo are easy for many people to look at and think, “That could never be me.”

It is observed that we have grown up in a society so saturated and dictated by the confines of gender that internalized misogyny exists in every single one of us. Some find it evident that we have all been indoctrinated by the mere existence of the world around us and that most of us are unaware of it.

“Misogyny comes into play within the patriarchy, a sociopolitical and cultural system that values masculinity over femininity, as defined by Tiffany Ferguson in her “I’m Not Like Other Girls” internet analysis video on YouTube.” wrote Gudenau. “Because of underrepresentation and misguided representation, misogyny becomes an ingrained cultural norm. Misogyny is perpetuated by our surroundings even in subconscious ways.”

To illustrate this in numbers: “One study found that women conveyed dialectic practices or internalized sexism on average 11 times per 10-minute increment of conversation (Bearman, Korobo v, Thorne, 2009),” wrote Audrianna Dehlin. “This shockingly high rate illustrated just how extensive internalized sexism truly is within society.”

Gudenau leaves her readers on an open note, imploring us all to undergo self-reflection and self-analysis. “When we grow up encompassed in a binary, gender norm-dominated, and sexist society, these thoughts become ingrained in our own heads unintentionally.

“Even when we may be aware of the gender roles and stereotypes at play, we still can internalize some deeply-rooted misogyny from what we’ve been taught. We must make a conscious effort to reconsider these thought processes and undo the damage.”