Literary publishing has practically always existed. However, in the 21st century, young writers are able to enter the field in ways they previously couldn’t, with lower barriers to entry and more guardrails.

“I got involved in the way that I think a lot of young people do, by seeing someone else doing it,” said Rishi Janakiraman, a poet and sophomore who attends Stanford Online High School. “For me, that was a poet who went to my school, Elane Kim. I wasn’t aware that young people could have that kind of recognition until I saw her be published.”

Literary publishing, consisting of digital and physical literary magazines, journals, presses, and competitions, offers young writers a variety of new ways to engage with their interests and get introduced to the wider world of writing.

Janakiraman, for example, has been published in online journals such as Rust & Moth, received gold keys from the Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards, attended a prestigious summer program run by the Adroit Journal, and edits for Polyphony Lit. This mix is typical, with youth who get involved in publishing often going all the way once they discover the opportunities at their hands.

The adults who assist and observe them — teachers, editors, and others — see the benefits of this.

“In eighth grade, it’s the first time most kids have ever applied to a contest. The idea that they could have something interesting and memorable to say that people would enjoy is new to them. Getting accepted or awarded teaches them that their voice matters and that transfers into knowing they have value as people,” said Jay Richards, an eighth-grade English teacher at Central Middle School.

Richards encourages students to submit to competitions like the BlueFire $1000 for 1000 Words Creative Writing Contest, the Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards, the National Council of Teachers of English’s Promising Young Writers Program, and the Daughters of the American Revolution’s American History Essay Contest.

Many youth also observe new freedom and understanding of themselves once they start writing for publication.

“Writing in isolation and writing for publication both lead to self-awareness, but in different ways. A lot of my poetry centers on identity, and it’s heavily informed by my own experiences and my culture. Being a writer has made me more self-aware and introspective in general. But I think being published by different magazines has made me more aware of myself as an artist and of how I express myself,” Janakiraman said.

Editing, too, offers youth a way to learn about writing and about themselves.

“Becoming an editor has helped me look at poetry and my own poetry more strategically, internally critiquing my work as if I’m a reader looking at it. I think it’s a unique perspective to gain,” Janakiraman said.

In addition to learning about themselves, writing and editing for literary publishing can help youth connect with other passionate young writers.

“I gained a community. I learned a lot about how other people wrote and how my writing could be improved. I also realized a lot of younger girls, like me, were involved in other literary magazines,” said Aiko Sugioka, a Design Tech High School sophomore who previously helped start and edit for a literary magazine.

Many youth feel that the chance to finally get their work published, meet other young writers, and hone their writing is priceless.

However, youth who are deeper into youth publishing begin to observe typical, concerning patterns.

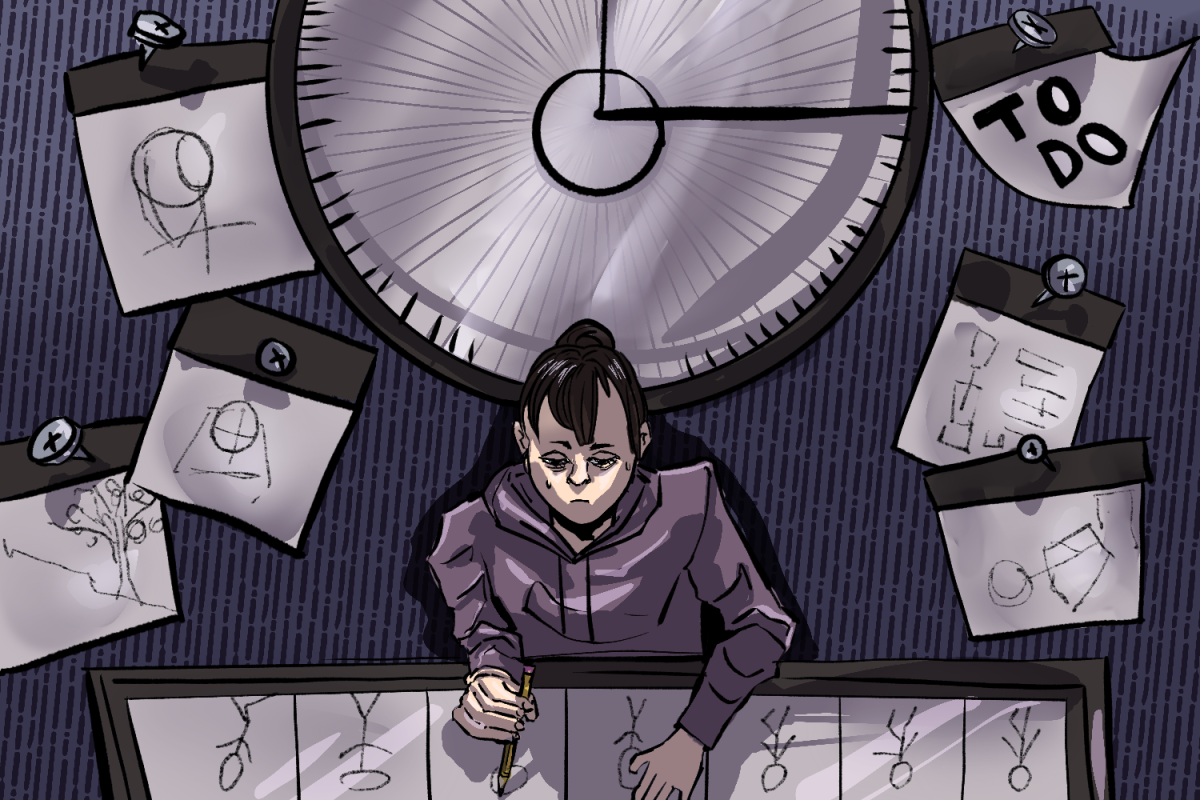

“When you’re trying to get published, there is this constant focus on meeting deadlines and making poetry that a wide audience will like. People seemed to like my poems, so I kept writing and submitting them. But sometimes, I didn’t even like the poems I was submitting,” said Jordan Groocock, a junior at Lick-Wilmerding High School, who briefly wrote for publications and slammed but stopped both upon entering high school.

In addition to the pressure of constant submissions, young writers can be drained by the space’s competitiveness.

“There’s this implicit culture of competition over the most prestigious publications or the most awards. I think this is because of college admissions. Instead of having a more collective approach to writing, it pits us against each other,” Janakiraman said.

Some young writers feel that, after repeatedly seeing that poems and prose writings that deal with the pain of language barriers with immigrant parents, being mocked for cultural food, or scolded for kissing someone of the same gender in their own and others’ work were most frequently successful, they started writing more about those specific experiences — whether or not they actually experienced them and whether or not there was something else they preferred writing about.

One topic that has become a staple in youth publications is “diaspora poetry.” Capable of beautifully exploring the realities of diasporic identities, it is also often mocked for being trite and appealing exhibitionistically to a white viewer — the frequently white judges and editors at literary competitions and magazines, perhaps.

In the novel “Martyr!” by Kaveh Akbar, the Iranian-American main character, Cyrus, is called out by his Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor, Gabe, for excessively writing diaspora poetry.

“‘I’ve read your poems, Cyrus. I get that you’re Persian. I know that’s a part of you. But you’ve probably spent more time looking at your phone today, just today, than you’ve spent cutting open pomegranates in your entire life. Cumulatively. Right? But how many pomegranates are in your poems? Versus how many iPhones?’” Gabe asks in the novel.

This type of writing is particularly common in youth literary magazines and competitions.

“A lot of competitions for young writers award work that centers diaspora and immigrant experiences — and in turn, a lot of youth-run literature magazines can overvalue diasporic work simply because editors have seen it win big,” Janakiraman said.

Writing by diverse voices is not always prioritized. In many cases relating to the wider publishing market, non-white authors feel they are given fewer opportunities for promotion and publication.

“As a minority in a primarily white space, you simply aren’t seen. Your work is considered exotic and not mainstream because it comes from another perspective,” said Yael Valencia Aldana, a creative writer, publisher, and professor at Florida International University.

Some writers also bring up the issue of permanence within the youth literary sphere — both too much and too little of it.

“Publication is something that’s very, very permanent. What you publish will stay on the Internet. I’m always afraid of people finding the works I published when I was 12 or 13 years old because it feels like people are going to recognize me by my older words and not my current style,” Janakiraman said.

Young writers may not be ready to take responsibility for their publicly available works. Some feel that they were not aware, when they started out, of how accessible their writing would become and regret publishing certain pieces.

Despite some writers feeling that youth publishing is too permanent, they also observe that the space as a whole lacks established magazines and communities.

“A lot of young people don’t start literary magazines because they truly want to uplift young voices, but as an extracurricular for their college applications. It’s sad because a lot of promising magazines die out after all of the editors-in-chief graduate,” Janakiraman said, adding that some magazines and journals avoid this issue by creating a hiring and promotion cycle.

In addition to the larger issues that young writers face, one constant fear is obvious. Rejection, the thought of a big, red “NO” being slapped on a personal piece, plagues every writer of any age. For young writers to acclimate, accepting rejection may be the most important mental shift.

“The major difficulty that most of us face is obviously rejection. Even if you expect that you’re going to be rejected, I can guarantee that you’re going to be rejected a lot more than you think you will. That took me aback at first, but I think it immediately prompts you to start being more self-reflective of your work,” Janakiraman said.

Despite the pain that rejection brings, it can be a crucial part of writing. Most writers, young and old, receive more rejections than acceptances. Stephen King’s popular debut novel “Carrie,” for example, was rejected 30 times before a publisher took a chance on it.

Rejections cause writers to revise and look at their writing from new angles. Especially in youth-centered magazines and competitions, many editors offer feedback on works they reject, allowing writers to grow from every opportunity they take. For young writers, accepting rejection and learning to build upon it is a crucial skill.

Another aspect of accepting rejection is simply realizing that it doesn’t always mean a piece is bad but rather that a magazine or press doesn’t think the piece fits within its aesthetic or theme.

“It’s part of the process every working writer needs to deal with, but it is bruising,” Aldana said.

Aside from accepting rejection, many believe that the most important thing for young writers is to focus on what they want to say with their writing and on developing a voice.

“The kids who I see have something they want to express. The whole idea of creating something meaningful out of writing is a really purposeful, rewarding activity,” Richards said.

The ideas that young people can express can be huge, but also about the smallest things they want to explore.

“I have always written about queerness because it has been a big part of my life. I used to also try to write commentary on issues in the world, such as gun violence or the environment. Now, I have taken the pressure off of myself,” Groocock said. “Sometimes, the most powerful work is simply about whatever the author feels like writing down that day, even if it’s mundane.”

Additionally, their style and voice will likely evolve as they mature — and through publication, which Janakiraman sees as good and bad.

“I feel like as a young person with a developing writing style, being accepted into certain journals very much changes my writing style. It’s improved my craft because the poems I was writing before were very trite and addressed surface-level themes, but it can be pernicious when it stifles different areas you want to explore. For example, if you get published by journals that prefer more standard work, it deters you from writing more experimentally,” Janakiraman said.

In the end, whether in the youth literary publishing circuit or not, many think that young writers should prioritize writing for themselves.

“I always wondered if people would get my most personal poems. In response, I cut out the ‘confusing’ parts and tried to make them more universal. Now, I have a small blue journal that I keep on my nightstand. Unlike before, I write in pen so that I am not tempted to erase or self-edit. If your art were never, ever going to be shared with anyone, what would you say? Would it be different from what you are saying now?” Groocock said.