In 1994, 7-year-old Megan Kanka was raped and killed.

She was living in New Jersey when Jesse Timmendequas, a known sex offender, moved into the house across the street without the knowledge of her family. At the time, there was no law that allowed the public to know about the whereabouts of sex offenders.

Horrified by Megan’s tragedy, the American people decided to pass a new federal law, now known as Megan’s law, in order to help prevent future cases of child sexual abuse.

The law was passed in 1994, and has since had several revisions. This included making an online list of all known sex offenders accessible to the public.

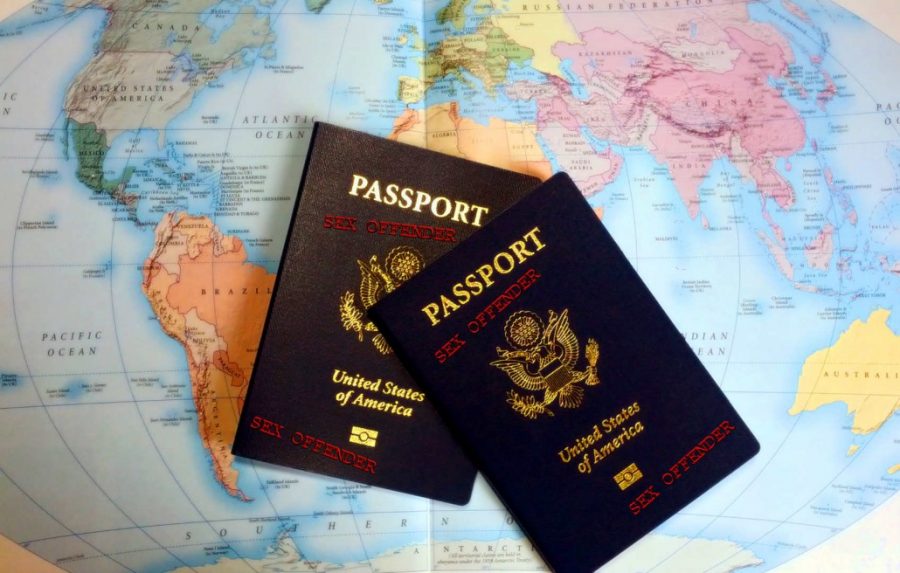

As of 2016, a new bill has been signed into law by President Barack Obama, called Megan’s International Law. The law requires all sex offenders who have committed crimes against minors to have a permanent stamp on their passports.

Megan’s International Law is meant to help prevent international child trafficking, and when I first heard about it I thought, without a doubt, that it would be an absolutely wonderful law. After all, human trafficking is still a big problem, with 800,000 people caught in the U.S. trade system alone. Carlmont students even spent weeks putting up informational fliers about it.

The law hopes to prevent trafficking by allowing authorities to much more easily track sex offenders when they leave and enter countries, hopefully thwarting any attempts to smuggling minors.

The law could also add an extra layer of security in airports that I would personally appreciate, as the staff of the airport would know of the individual’s criminal history.

So, what could be the issue with a law that seems to do nothing more then protect minors from vile, disgusting people?

The issue is that it actually does a lot more than just protect children, which is why six sex offenders challenged the law almost immediately after it was passed. According to a SFGate article, the offenders claimed that they would be exposed to harassment and harm for crimes that had nothing to do with sex trafficking.

Originally I thought that their argument was completely invalid, and so did San Francisco judge Phyllis Hamilton, who recently threw out the case. At first glance, it seems like a good idea to have all sex offenders’ passports stamped, whether or not their offenses were related to child trafficking.

However, what the law forgets to take into account is that not all sex offenders are actually vile, disgusting people.

In the U.S., what counts as a child sex offender is not always the movie portrait of a sexual predator. It could be a 17-year-old girl who sends nude photographs to her boyfriend or two teenagers having consensual sex.

With this law, someone who was caught having consensual sex in high school 20 years ago will end up with the same stamp on his passport as someone who has raped a little girl.

In other words, the six sex offenders were right to some extent. The law does indeed wrongfully harm some of those who have committed a “sex offense” against a minor.

However, that does not mean that the law should get thrown out, as the six sex offenders suggested. It doesn’t mean that only those who have a criminal record for the sex trafficking of minors should have a stamp either.

If that were the case, people like Timmendequas would get a free pass.

What we need now is a revision of U.S. laws surrounding minor consent and “possession of child pornography” that draws a clear line between an actual sex offense and consensual sex among teenagers.

Still, laws take a long time to change, so until then, Megan’s Law should take the time to differentiate between these different types of “child sex offenders.”

The law should in the very least have different types of stamps depending on the severity of the offense. Better yet, the law should just leave out some forms of sexual offense altogether.

Despite all of its issues, Megan’s International Law ultimately indicates progress. It serves as a platform for future laws that deal with protecting children from human trafficking, and it will help to prevent this crime.

The law should by no means be abolished. It just needs a little revising.