“To be, or not to be” is the question that school departments should ask themselves when discussing the future of Shakespearean-heavy curriculums. From “Hamlet” to “Julius Caesar,” nearly all high schoolers have suffered through countless Shakespeare plays in their English classes.

According to a nationwide survey from Whittier College, 93% of schools require students to read “Romeo and Juliet.”

“I think that replacing some of Shakespeare’s works might perhaps be more enjoyable to students, but I do also know of students who enjoy reading ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and feel a sort of sense of satisfaction at mastering a challenging text,” said Addison Gaitán, an English I teacher at Carlmont.

While there is value in having teens analyze classic Shakespearean literature, it would be more beneficial to diversify the range of novels students read. This matter goes beyond the entertainment of students, it brings up the topic of diversity and inclusion in school curriculum.

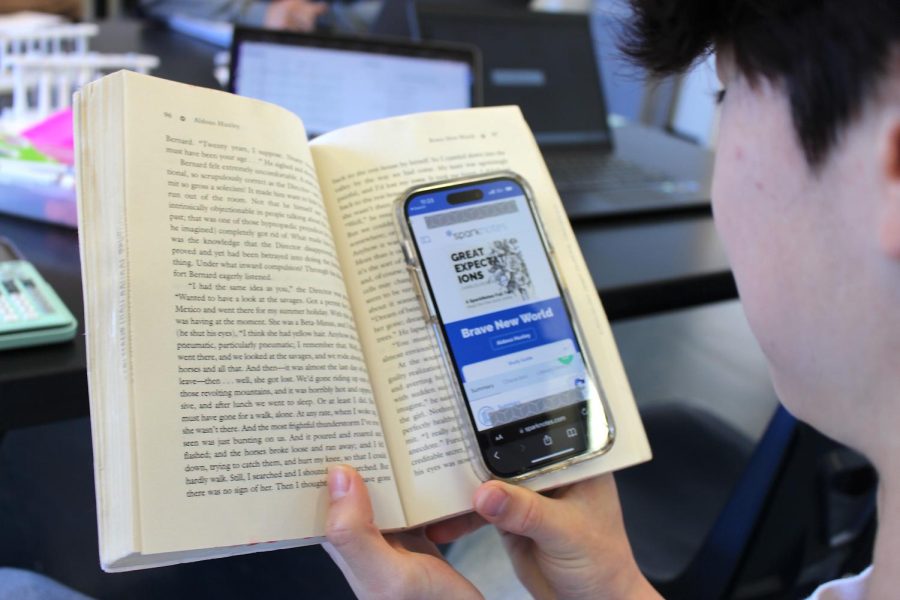

Other common novels included in American English classes, such as “The Great Gatsby,” “The Catcher in the Rye,” and “Great Expectations,” are all works written by white men.

Oftentimes the most impactful books are those that connect to current event issues, which, in today’s society extend to many different backgrounds; so how are students supposed to analyze those modern topics solely from the perspective of the most privileged people in society?

Not only does this narrow the novels’ relevance in today’s world, but it also makes it more difficult for students to relate to what they are learning in class.

According to Edutopia, a website published by the George Lucas Educational Foundation, a “curriculum that’s culturally responsive and grounded in identity work is relevant and engaging, as it helps students better understand not only their own history and truth but those of others.”

Students feel the most motivated during school when they feel a personal connection to their work. There is nothing personal about reading what was considered a “dramedy” back in the 1500s.

In addition, class discussions and literature analysis are the basis of English courses by allowing students to share their points of view and main takeaways. However, with Shakespeare units, kids are overlooking the important themes because they are struggling just to understand each sentence.

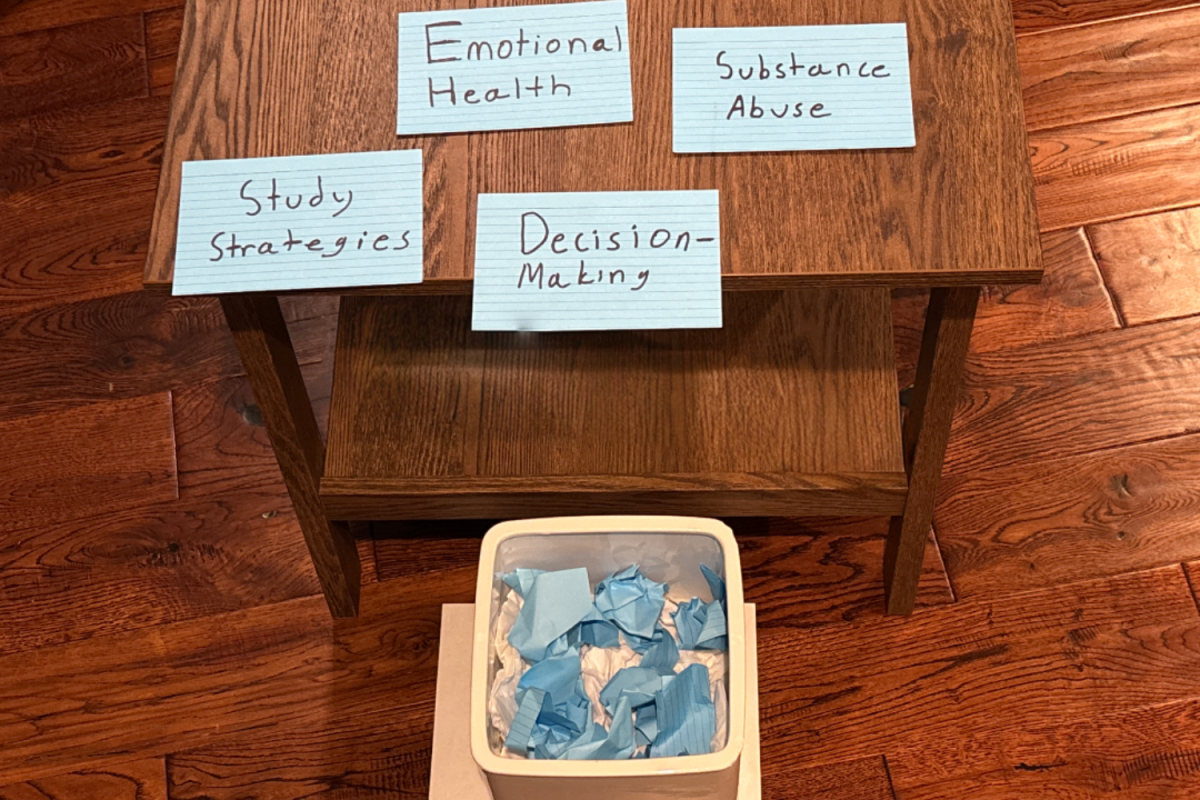

“I think classes should ideally have a balance between more modern literature that reflects students’ diverse lives and experiences but also expose them to canonical works that are referenced in so many other texts, pop culture, and other parts of academia,” Gaitán said. “It’s definitely a fine balance to achieve.”

Over the years, schools have begun to implement more books from women and people of color such as “Little Women,” by Louisa May Alcott, and “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” by Zora Neale Hurston.

However, the list should not end there. Curriculums should also include a large assortment of books and authors in their English classes, such as “The Color Purple,” by Alice Walker, “Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit,” by Jeanette Winterson, and “Pachinko,” by Min Jin Lee, just to name a few.

Reading about stories that include diverse backgrounds is an extremely impactful way for students to learn. It brings up questions and discussions about race, sexuality, and experiences that cannot be taught through Shakespearean plays.

Students should have the freedom to learn beyond the lens of a white male, and be able to explore topics that reflect our current progressive society. It is time for books that are considered to be “classics” to be rerouted.

“I wanted to become an English teacher in particular because I think that the subject can help us learn so much about ourselves, human nature, and the lives of others,” Gaitán said. “Hearing from a wide variety of writers certainly helps us to achieve this.”