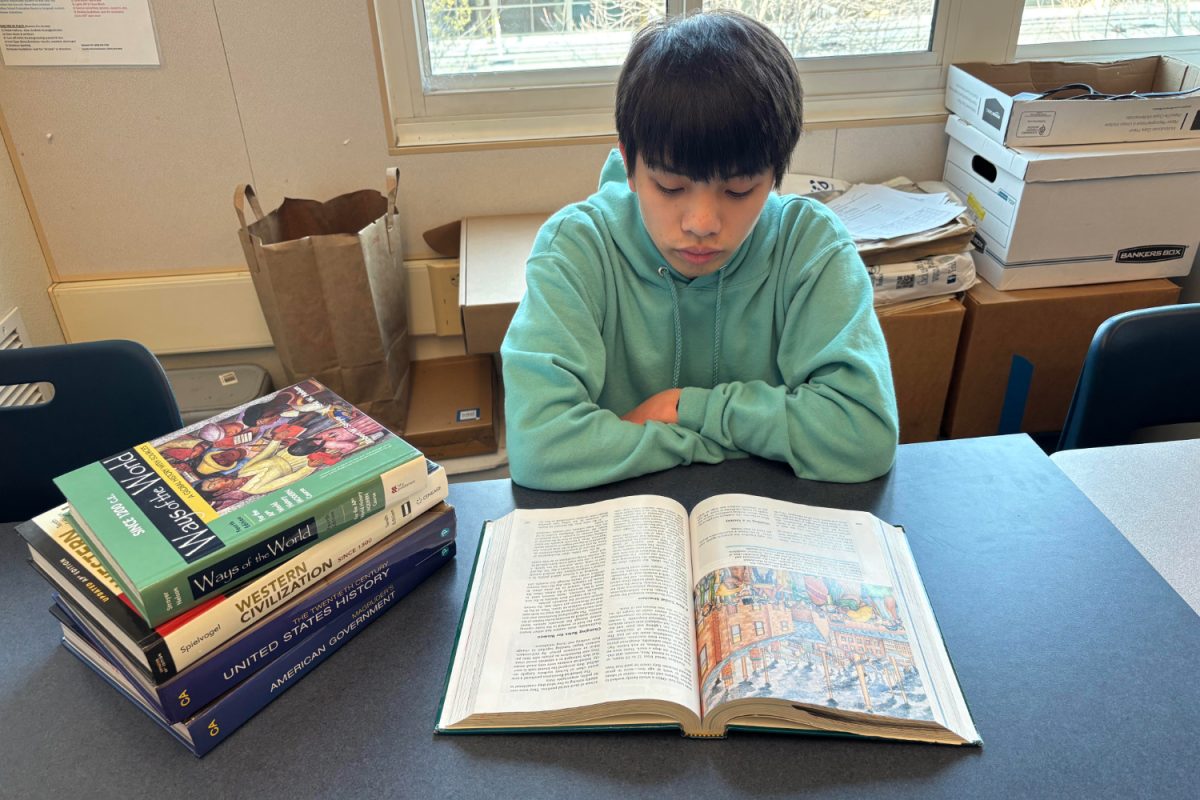

“When are we going to learn real history?”

After a semester of Carlmont’s relatively new and adaptive ethnic studies course, freshmen wonder why “history” changed so much.

Because students don’t learn traditional interpretations of history in ethnic studies, they consider the course to be unnecessary and counterproductive; they often fail to understand why the course became a district graduation requirement in 2020.

Ethnic studies differs from traditional history courses in that it “aims to leverage existing methodologies to question dominant narratives,” according to Sequoia Union High School District’s description of the course.

It is both incorrect and dangerous to label ethnic studies as a “fake” history. Students must recognize that history cannot be “correct,” like the answer to an algebra problem.

Carlmont’s history courses must stress that history lies in the interpretation of agreed-upon facts.

“Mere facts don’t have meaning. They must be given that meaning by human beings,” said historian James M. Banner Jr., writing in Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Different fields of history present invaluable narratives of the same historical events. For example, history can be analyzed as the actions of governments (political history) or through the experiences of ordinary people (social history). Comparing different interpretations of history is essential for understanding the present.

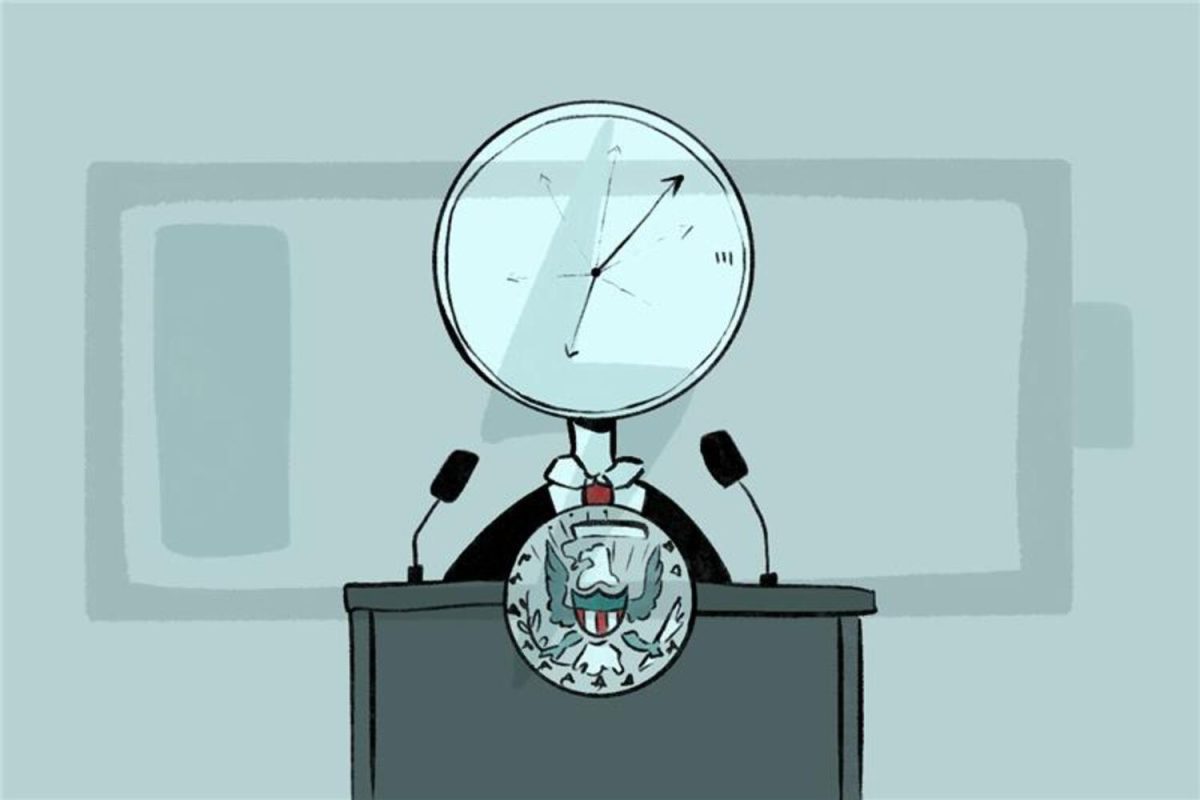

Take Abraham Lincoln, for instance. According to the Siena College Research Institute, scholars and the public often rank Lincoln as one of the greatest presidents in American history.

His legacy as a promoter of freedom and social equality for African Americans is undeniable. Or is it?

Lerone Bennet Jr., a social historian who wrote several books on African American history, famously called Lincoln a white supremacist in 1968, claiming he opposed true equality.

President Donald Trump has also made controversial claims surrounding Lincoln and called himself the better president in 2022.

For Carlmont students to become “creative thinkers who are confident and collaborative in a rapidly changing society,” as Carlmont’s mission statement outlined, fringe claims can’t be ignored. Instead, they must be challenged.

Carlmont students’ ability to think critically about history has never been more crucial, especially as political agendas continue to impact education nationwide.

While it is true that claims like Trump’s can be debunked easily, dangerous interpretations of history are more challenging to notice in many cases.

For instance, historians agree that Christopher Columbus set sail for the Americas in 1492. However, Columbus did not “discover” the Americas in 1492, as many claim.

This claim became commonplace because of the prejudiced belief in Europeans’ superiority, which retains influence today. According to the Pew Research Center, sixteen states still observe Columbus Day as an official public holiday despite opposition from Native Americans and others.

History almost always reflects who is telling it. Whether through divisive claims about the past on social media or a seemingly innocent textbook, historical interpretations are meant to be examined critically.

“Robust, free arguments about the realities, significance, and meaning of the past should be cherished as an integral element of an open society like the one ours strives to be,” Banner said.

Courses at Carlmont must increasingly emphasize that history is more than facts through adapting courses.