The loudspeaker announces a duck-and-cover drill. Students giggle and roll their eyes as they reluctantly crawl under their desks. A few choose to continue working and ignore the announcement, refusing to get out of their seats. These reactions to drills are common for Carlmont. High schoolers find it challenging to take these exercises seriously since many have been practicing them from kindergarten.

“I think drills are effective in preparing for emergencies, but I also think that they are a waste of time because you cannot do work during that time,” said Grace Xu, a sophomore.

It is an unavoidable fact that drills take away from work and class time. However, despite the inconvenience, they are effective in preparing people for emergencies. According to the National Fire Protection Association, from 2013 through 2017, an estimated 3,320 structure fires occurred, but only about four fatalities occurred during the four-year span.

Before proper safety protocols were enforced, the Our Lady of the Angels school fire in 1958 became the deadliest school fire in U.S. history. The school passed a loose fire safety inspection months before the disaster, yet it lacked any sufficient fire equipment and training. When the fire broke out, students were trapped and suffocated in their classrooms. Ninety-five people lost their lives. Authorities learned their lesson after the tragedy, implementing strict fire safety regulations.

“The purpose of drills is for teachers and students to go through the motions, so we know what to expect, especially students who come in from other schools or incoming freshmen,” said Dan Nguyen, a math teacher at Carlmont.

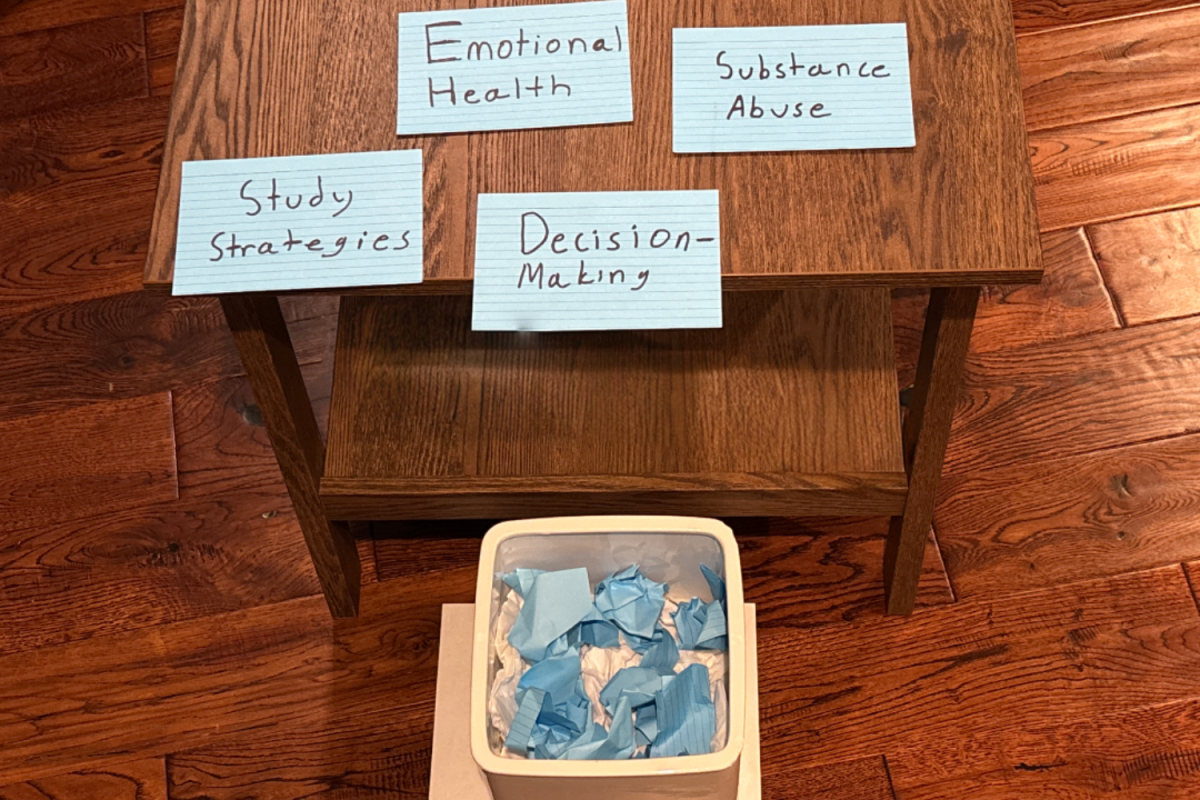

Fire evacuation drills, along with duck-and-cover, are the most practiced. California state law requires elementary and middle schools to have four evacuation drills per year, and high schools are mandated to have two. By ninth grade, most students have practiced 36 fire drills, giving them plenty of experience. Even the students who slack off have the necessary expertise in the case of an emergency.

“We do these drills so many times I already know what to do during an emergency, so it’s not a big deal when kids don’t take drills seriously,” said Mackenzie Young, a sophomore.

Despite the practice for common emergencies, drills still must occur, to keep up with evolving dangers in the classrooms. The secure campus drill is practiced twice a year at Carlmont, to protect the campus against threats to the community. Teachers are given extensive training beforehand and are taught the proper steps to take in an emergency. During the drill, students are told to blockade the classroom entrance with desks and chairs then hide in the corners of the room. In a real shooting, the assailant only has a few minutes before the first responders arrive, and a blockaded classroom can discourage the attacker from entering.

“Everything’s changing with the increase in shootings, we need to be prepared, so we take the active shooter drills very seriously,” Nguyen said.

Since the tragic 1999 Columbine high school massacre, school shootings have drastically increased. According to the Pew Research Center, 57% of teens now worry about school shootings. Extra drills have been added to protect against this new threat. From 2004 to 2016, there was a 13% increase in the number of schools that had school shooting procedures, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

“The violent intruder drill is the most important because other emergencies, like earthquakes and fires, are more predictable. But with a violent intruder, it could take on so many different forms,” said Kristine Govani, a computer science teacher.

Despite desensitization to the gravity of the drills, responses to emergencies must be taught to students, so in the case of a real emergency, they automatically act.

“We all get ho-hum about drills, but I do think they prepare us for possible emergencies. Drills are like anything else; practice makes perfect,” Govani said.

In an emergency, anything can happen; the announcements don’t work, the door’s lock is broken, the teacher is not in the classroom. But drills can prepare students for the worst, even if nobody takes them seriously or valuable class time is wasted. Practice can be the difference between life and death in an emergency.