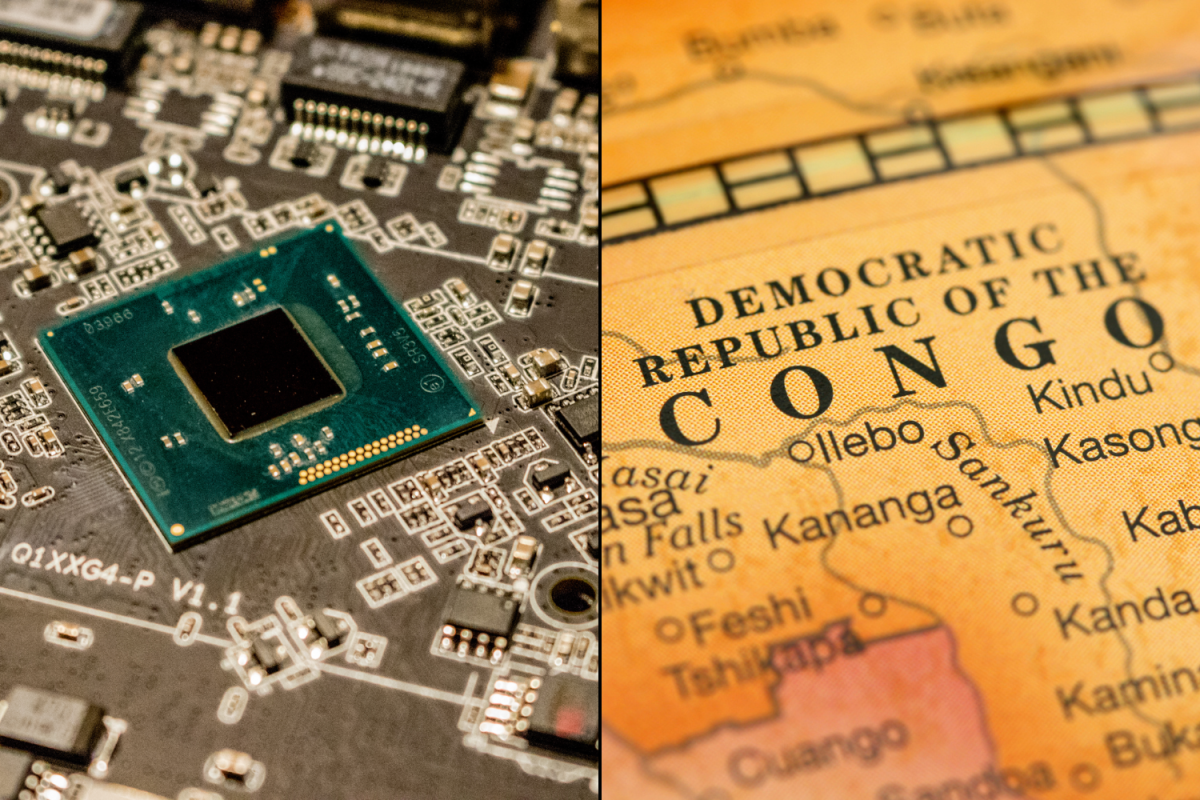

The batteries in electric vehicles, smartphones, and computers come from minerals sourced from a war zone. What many see as the hallmarks of technological development doom others to a life of modern-day slavery.

Tin, tantalum, tungsten, gold (known as 3TG), and cobalt are all essential components of products that fuel the entire technology industry, and they come straight from the life-threatening work of miners in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). According to the Cobalt Institute, the DRC contains 75% of the world’s cobalt supply. This cobalt is needed to manufacture lithium-ion batteries in phones, computers, and electric vehicles. As the demand for these new technologies increases, the pressure beats down on the people who work in mines in the DRC in inhumane conditions.

3TG minerals and cobalt are labeled today as “conflict minerals,” in other words, minerals sourced from conflict zones and exported worldwide. Most of the DRC’s cobalt supply is extracted by artisan miners working for a few dollars daily. They hack at minerals in trenches for hours, exposing themselves to cobalt, which is toxic to touch and breathe.

According to the Bureau of International Labor Affairs, these miners can even be young children. While the use of child labor for mining is outlawed in the DRC, enforcement of such laws is often weak. Tesla, Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Dell all faced a lawsuit from International Rights Advocates in 2019 for “knowingly benefiting from and aiding and abetting the cruel and brutal use of young children in the Democratic Republic of Congo to mine cobalt.”

Tech companies are not helpless in the face of exploitation. There is a lot that they can do to help the miners in the DRC. Applied Materials, for instance, a corporation that supplies equipment for the manufacture of semiconductor chips for electronics, is part of the Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), a coalition dedicated to fostering social responsibility in supply chains.

RBA has undoubtedly made an impact when it comes to making significant strides towards responsible mineral sourcing. Their Responsible Minerals Initiative offers companies a third-party audit verifying that smelters and refiners align with current global mining standards. Additionally, they engaged with non-governmental organizations, investor groups, and government institutions to address issues with mineral sourcing.

“I believe the RMI is an excellent initiative. Individual companies are less powerful than groups of companies in driving change, and such an industry consortium approach is very powerful,” said Christopher Librie, the director of the Environmental, Social, and Governance Group at Applied Materials.

However, the difficulty many companies encounter when attempting to be more responsible in their mineral extraction is further down the supply chain.

“Applied has good communication and control over our “tier one” suppliers – those who supply Applied directly. They, in turn, have good control over “tier two” suppliers – those who supply our tier one. As you go deeper into the supply chain to tier three or four, communication and controls become more challenging,” Librie said.

Companies like Tesla and Apple rely on suppliers lower in the supply chain to sell them conflict minerals. These same suppliers also provide companies with information about the origin of their minerals, including ones they obtain from lower-tier suppliers and smelters.

It’s a complicated network that becomes increasingly obscure as the minerals pass through different suppliers. This makes it difficult for companies to maintain communication with their suppliers and get accurate information about the sourcing of their minerals.

“Companies like Apple, Hewlett Packard, and Amazon have millions of consumer devices that contain conflict minerals. It is much harder for them to trace their suppliers’ ethics,” Librie said. “When I worked at Hewlett Packard, an entire department was dedicated to this issue. They had sent numerous executives to tier three and four level suppliers to conduct fact-finding and audit studies just for this purpose.”

We should applaud companies that have eliminated their use of conflict materials entirely from their manufacture. On the other hand, we should put pressure on companies that rely heavily on these materials. They are not powerless in the face of exploitation. By looking towards recycling cobalt or using other minerals in technologies, companies can advance in the direction of ethical sourcing practices and have a tangible impact on the people in the DRC.

The tech industry needs to be held accountable for its impact on the exploitation of workers in the DRC. They are in a position to change the conditions for miners in DRC and must do all in their power to assume responsibility. By establishing clear policies for responsible mineral sourcing and enforcing them with their suppliers, companies can better ensure that they are not contributing to exploitative conditions in the DRC. Furthermore, by conducting regular supply chain audits, companies can verify that their suppliers comply with these policies and increase their communication with them.

A world in which some have leading technologies at their fingertips and others are living in fatal working conditions is unacceptable. Technology development must coincide with the elevation of better labor conditions worldwide.