Proposition 29, which would have imposed more regulations in dialysis clinics has failed for the third time in a statewide California election since 2018.

The appearance of another dialysis-related proposition had many voters scratching their heads and asking “haven’t we rejected this before?” In the end, 69.9% of voters voted “no” on stricter dialysis regulations.

According to Ballotpedia, if Proposition 29 passed, dialysis clinics in California would have been required to have a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician’s assistant on-site at all times. Other measures of the proposition included requiring dialysis clinics to report infections to the state and obtaining written consent from the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) before closing or substantially reducing services to patients.

The proposition also requires dialysis clinics to inform patients and the CDPH of physicians with more than a 5% share in the clinic and to not discriminate in who they treat regardless of the method of payment.

According to the National Health Service, dialysis is a treatment for kidney failure where a machine pumps out the patient’s blood, cleanses it of toxins and waste, and pumps it back in. There are 80,000 dialysis patients in California that go through the treatment three times a week, sitting in a chair for multiple hours each time.

Proposition 29 was largely championed by the healthcare workers’ labor union Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West (SEIU-UHW) and opposed by the two largest private dialysis care providers in California: DaVita Kidney Care and Fresenius Medical Care. Critics of the proposition argued that SEIU-UHW was using the ballot proposition to unionize dialysis workers, claims that SEIU-UHW denied.

Like Proposition 29, two propositions brought onto the ballot by SEIU-UHW with similar requirements, Proposition 8 in 2018 and Proposition 23 in 2020. Both failed in their respective elections.

According to SEIU-UHW Press Secretary Renée Saldaña, the propositions were created due to patient complaints about the quality of care in dialysis facilities, and the healthcare union has been working towards reform for many years.

“Dialysis care is in crisis. Vulnerable patients’ lives are at risk, and we urgently need these changes under Proposition 29 to protect patients and improve the care they receive the current model of the dialysis industry — it’s predatory, it hurts patients and consumers,” Saldaña said.

Saldaña also noted that dialysis clinics are more lucrative than perceived.

“It’s essentially a duopoly in California: two corporations called DaVita and Fresenius operate approximately 75% of California. They are massively profitable. And so far they’ve been doing everything possible to stop patients and workers from improving the quality of care inside these clinics,” Saldaña said.

According to Saldaña, the multiple dialysis sessions per week impose a lot of stress on a patient’s body and mind.

“Patients pass out, they suffer strokes, they can have heart attacks, or oftentimes, I’ve seen patients that even sent me pictures where they bleed uncontrollably during these treatments,” Saldaña said. “They say it’s terrifying. Dialysis patients need a doctor on site who can handle these life and death situations.”

But it is not clear if the public was aware of what the proposition meant, and that was where money and advertising came in. Misinformation was also spread by these advertisements, according to Saldaña.

“The dialysis industry has already spent $86 million on billboard advertisements, and even within dialysis clinics, we hear patients say that they’re just plastering the walls with ‘NO on 29’ and handing out tote bags and coffee mugs and stickers. One of the top lines I hear from people is, ‘this is gonna close clinics.’ But there was actually something written in [Proposition 29] to keep clinics open,” Saldaña said.

Saldaña was referring to a provision that would allow small or rural clinics to apply for year-long exemptions from being required to have a licensed medical professional onsite at all times.

However, the opposition argues their advertisements are justified.

According to Kathy Fairbanks, a spokeswoman for the No on Proposition 29 Coalition, requiring a licensed medical professional at each dialysis clinic seems like a good thing, but this is how SEIU-UHW phrases the ballot in their favor. The coalition Fairbanks represents is largely funded by DaVita and Fresenius Medical Care.

“The independent nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office has concluded that Proposition 29 would increase clinic costs by several hundred thousand dollars per year per clinic for a physician that’s not necessary. Every dialysis patient has a nurse, technician, social worker, and dietitian that tend to the patient. Each also has his or her own nephrologist or kidney doctor who is the only one that can change the dialysis treatment or medication,” Fairbanks said.

Additionally, according to Fairbanks, the regulation in the proposition that requires clinics to ask the state before closing is illegal.

“There is a provision in Prop. 29 that says prior to closing the clinic, it would need to go to the State Department of Public Health to get approval. It’s illegal, according to the US Constitution and the state constitution, to engage in taking someone’s property, so you can’t force a business that is operating in the red — meaning it can’t cover its costs — to stay open,” Fairbanks said.

This is contradicted by Saldaña, who claims that hospitals are already required to ask the state before reducing care, so it would be legal to require dialysis clinics to do so too.

“One of the main opposition talking points we’re hearing is that ‘Oh Prop 29 would force us to close the clinics’ and it’s like no, Prop 29 would require [clinics] to get approval from the state to reduce or close services. Hospitals are already required to do this in California and Prop 29 would ensure dialysis clinics are held to the same standard,” Saldaña said.

In response to concerns over emergency situations occurring in dialysis clinics, Fairbanks said that the presence of a doctor is redundant.

“The best place for [a patient with an emergency] is to call 911 and get them to a hospital. The specialized dialysis centers are not hospitals, they are outpatient clinics, specifically to provide dialysis treatment. If someone were to have a heart attack, they have to go to a hospital. Every doctor would agree with that. Every nurse is trained in CPR, so a doctor isn’t adding any benefit. They’re just an additional cost,” Fairbanks said.

A large portion of dialysis clinics’ staff is composed of dialysis technicians, a job that only requires a high school education and training course, according to Best Colleges. They do not have to attend university or medical school. Clinics are federally required to have a licensed medical professional as their medical director, but these medical directors are not required to spend a set amount of time at the facility, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

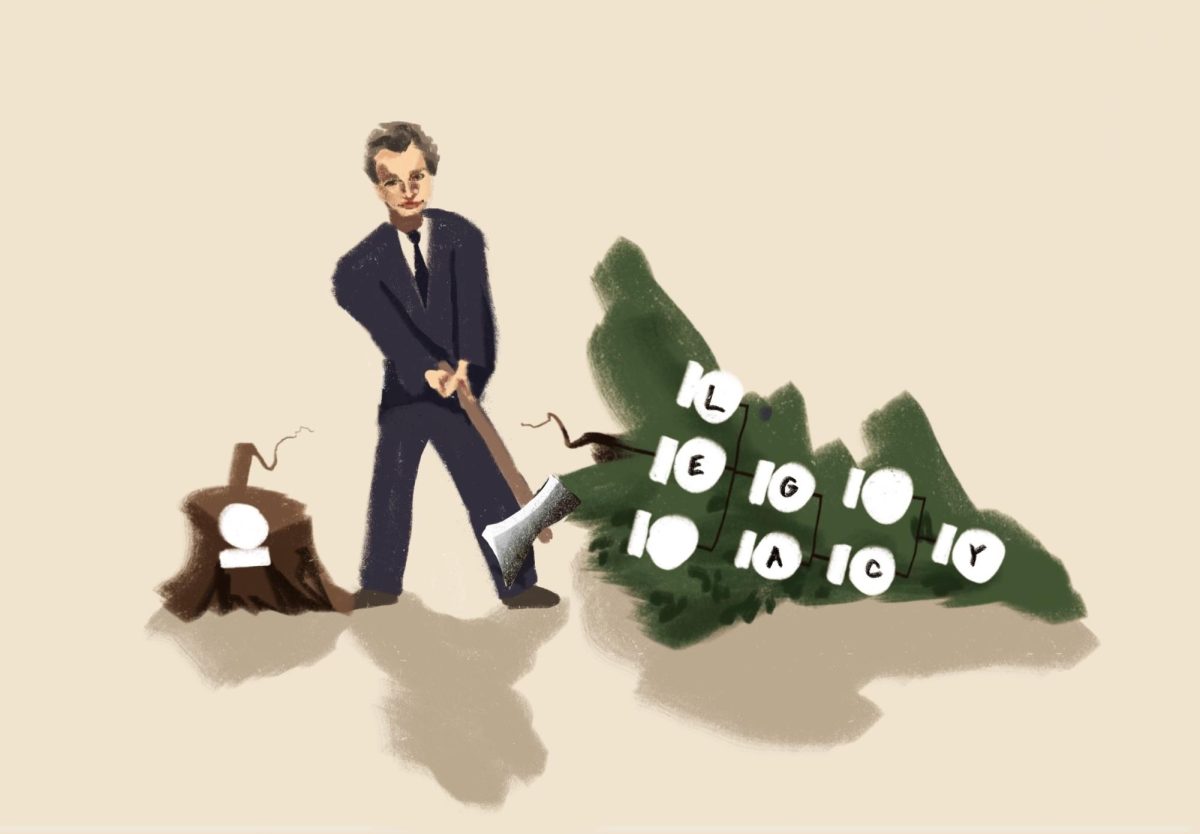

Furthermore, Fairbanks believes that the reason behind SEIU-UHW’s continuous efforts to put propositions on the ballot is not to improve patient care but to deal a blow to large dialysis clinics such as DaVita in order to pressure them into allowing dialysis workers to unionize. Her suspicions stem from the lack of action on the “yes” side.

“[SEIU-UHW] make $110 million per year from their union dues, and we know that because they have to file reports with the IRS. They have plenty of money but they haven’t even tried to do anything for free,” Fairbanks said. “They haven’t set up a Facebook page. They haven’t used social media at all. And I’m not even talking about buying ads.”

According to Fairbanks, DaVita’s large expenditures for advertising are necessary because of a lack of knowledge about the issues of the proposition.

“It’s left to the no campaign to educate voters about the consequences. There are 80,000 dialysis patients in California, and there’s absolutely no question that dialysis clinics will close. The very favorable wording makes our job more difficult and more important to make sure voters understand that a ‘yes’ vote harms dialysis patients,” Fairbanks said.

Both sides of the Proposition 29 ballot agree that the proposition would impact the lives of dialysis patients, but disagree on whether the passing or rejecting of the proposition would harm patients. With voters being told that their decision had the power to threaten the lives of dialysis patients through ad campaigns from the No on Prop 29 Coalition, contradictory information contributed to more voters bubbling in the “no” box on their ballots.

“Campaign money spent on ballot initiatives is more effective when it’s on the no side because people, when there’s a lot of competing information, might default more towards doubt,” said Jason McDaniel, an associate professor of political science at San Francisco State University, where he has taught for 13 years. His research focuses on elections and urban politics.

McDaniel agreed with Saldaña that proposition campaigns that stirred up fear in voters were more likely to cause the proposition to fail.

“The easiest thing to do in any campaign is to get some sense of anxiety, doubt, or fear. It’s a very common tactic,” McDaniel said.

But there is more affecting public opinion. According to McDaniel, for propositions that require more specific knowledge, such as of dialysis and the healthcare system, it is difficult for regular voters to decide what their views are, revealing flaws in the proposition system process.

“[As voters] we’re being asked to make decisions that are complex, that we often aren’t capable of making. That’s what a deliberative legislative process should be for. I think [the proposition system] can be abused in that regard,” McDaniel said.

According to McDaniel, corporations or special-interest groups can use the ballot proposition system as a pathway to circumvent the legislative process to pass legislation they want.

Moreover, McDaniel acknowledges the disparity between the amount of money spent on campaigns by dialysis clinics and SEIU-UHW — DaVita and Fresenius Medical Care have spent around 80 million dollars on the no campaign compared to around 8 million dollars spent by SEIU-UHW — as a sign of the proposition’s failure.

“When the yes side is only spending less than around 10 percent of the no side, it is really hard to pass [a proposition],” McDaniel said.

Akin to Fairbanks’ comment on the public’s lack of knowledge about dialysis, McDaniel believes that voters can learn, at least at a low level, through campaign processes. He says that learning is more prominent and important when there is a ballot initiative that is not clear from a partisan’s point of view, and an example is Proposition 29.

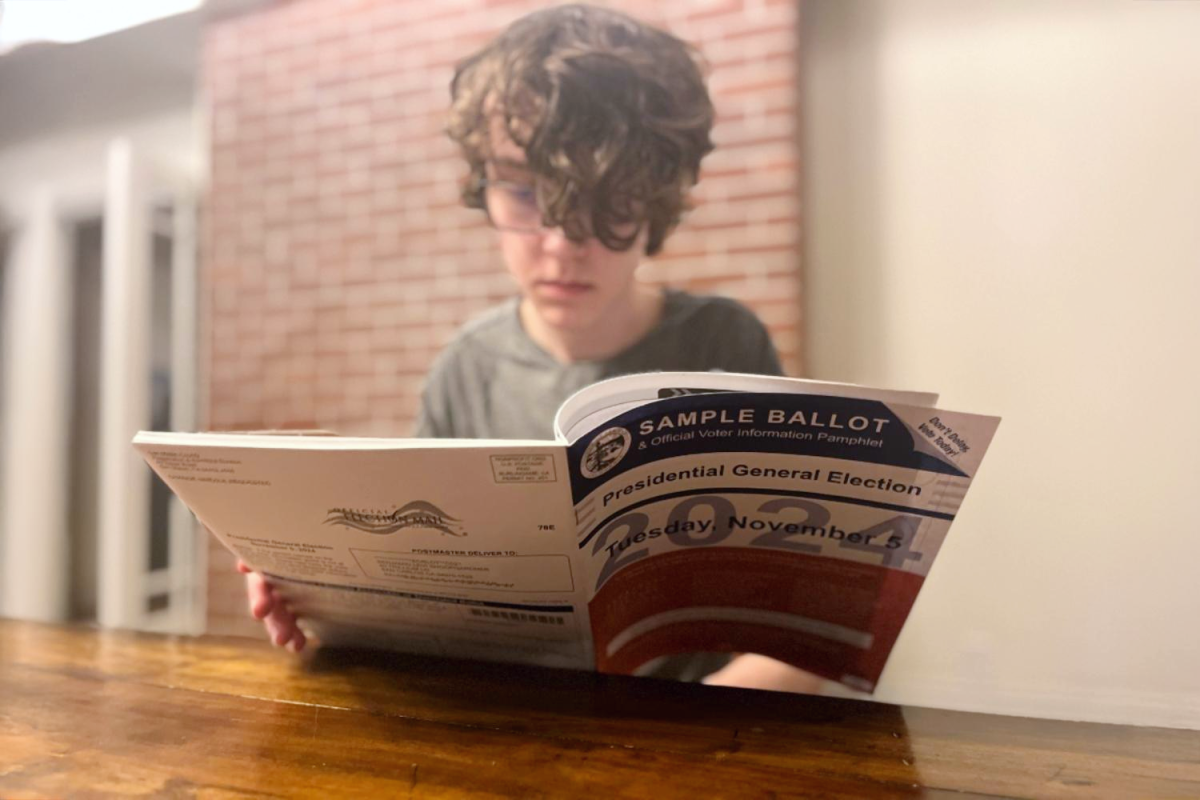

The uncertainty shrouding Proposition 29, caused in part by the frequent advertisements from the No on Prop 29 Coalition, has reached more than adult voters.

“I’ve gotten a lot of ads about [Proposition 29]. It makes me feel very unprepared for voting in the future because I don’t know enough,” said Cecilia Baranzini, a sophomore at Carlmont.

Despite being a minor and the lack of information, Baranzini has begun to make her own decisions about Proposition 29 with the help of the opposition campaigns and says that she would have voted “no” if she was of legal age.

Overall, propositions such as Proposition 29 put pressure on voters to make important decisions on topics they cannot be expected to have adequate knowledge about.

“As a political science professor, I’m often asked, ‘Explain these things to me,’ and I don’t know. I don’t study the details of budgeting and laws. If I’m going to do that I can spend some time to do it. And hopefully, I’ll understand it, but I’m relying on other experts to tell me. [Voters] should not be expected to know the ins and outs of all of these pieces of constitutional amendments,” McDaniel said.