Redefining the canvas: blurring the lines between vandalism and art

Graffiti is a crime — unless it’s worth millions at an auction.

For decades since its initial popularization, the public has scorned graffiti, and graffiti artists have risked arrest and fines in order to create bold, unfiltered works in public spaces. Yet, those same styles are commodified in museums and galleries. This double standard raises an essential question: can graffiti truly be considered an art form?

Modern graffiti emerged in New York City during the 1960s and is widely recognized for its stylized lettering and bold, striking colors. At the height of its popularity and even today, many teens and gangs saw graffiti as a means of self-expression and a way of leaving their mark on the world.

“I think the art of graffiti itself can be very beautiful, but I can understand that people would not want it on their buildings,” said Julia Schulman, the department chair of visual arts at Carlmont.

What defines art can be controversial, but many believe that art can be considered any form of self-expression, ranging from splashes of paint upon a canvas to intricately rendered paintings. This widespread controversy has raised the question of whether or not graffiti can really be classified as “street art,” or if it is merely a lowlife act of vandalism.

Graffiti is a global phenomenon, adorning walls and structures in cities like London, Los Angeles, Paris, São Paulo, and beyond. However, New York City is widely considered the birthplace of modern graffiti.

During the 1960s and 1970s, graffiti started becoming more popular amongst youth as a form of expression in New York City, according to an article by Priya Parmar, an associate professor at Brooklyn College, and Bryonn Bain, a professor of African American Studies.

“I think there’s a reason graffiti started in pretty urban areas that are also considered to be pretty poor,” said Baltazar Cid*, a former graffiti artist from the 1990s. “It was like leaving your mark on the world, regardless of whether people liked it or not.”

Cid grew up in Anaheim within a community that was a relatively low-income area with a predominantly Mexican population. It was a working-class community, and his parents only spoke Spanish.

The first time Cid saw graffiti was when he went to Los Angeles, and he was amazed by the large-scale paintings and murals he saw on the walls. As he got older, he started seeing more graffiti around his neighborhood in Anaheim, in an array of different styles.

“There was some gang-style graffiti, which looks more like Old English with different types of letters that look a lot more like calligraphy, or what you would see in tattoos,” Cid said. “Then, there was the abstract, colorful stuff that I was really attracted to.”

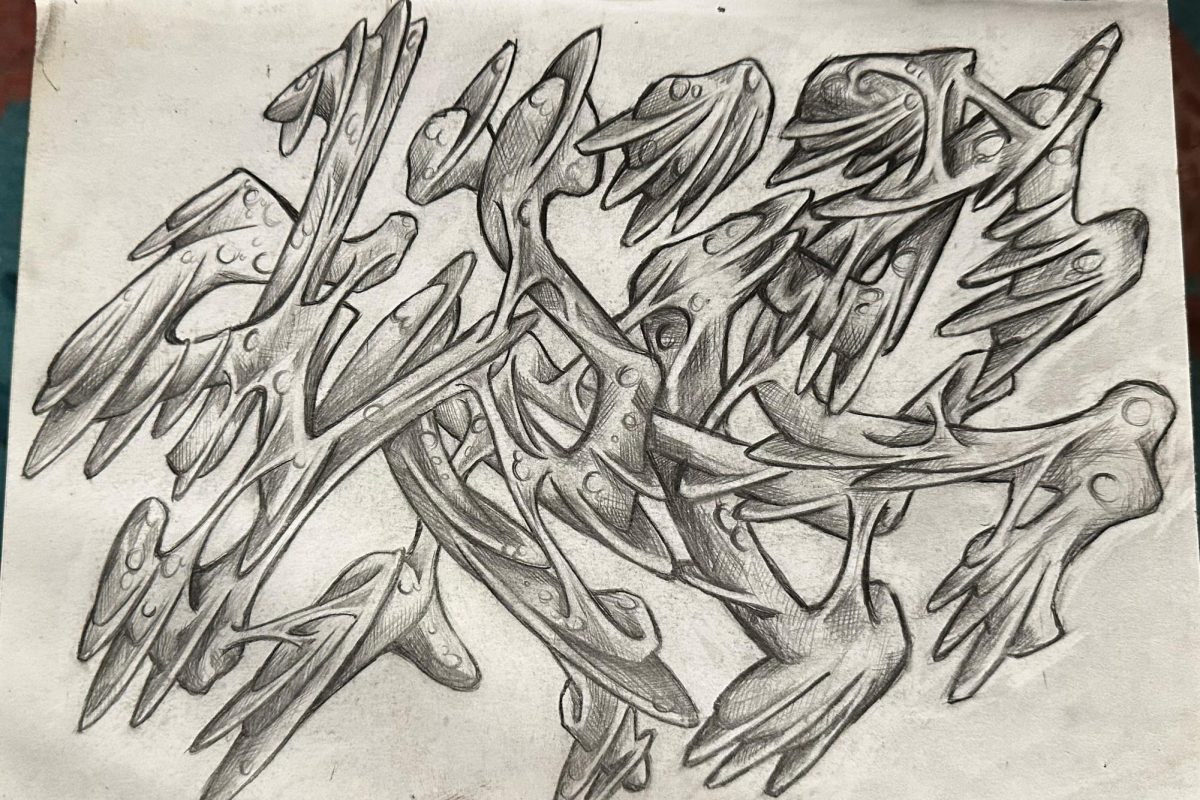

In his freshman year of high school, inspired by the graffiti he was surrounded with, Cid began practicing the style in his sketchbooks and developing his tag, which is considered a signature that most graffiti artists develop for themselves.

According to Koon-Hwee Kan, an associate professor of Art Education at Kent State University School of Art, the invention of magic markers and the improvement of spray paint during the late 1960s made tagging more accessible and popular to people in the United States.

“You have to choose your name, so I just opened up a history book and looked for cool words,” Cid said. “All my friends had multiple names that they’d change up all the time, and I didn’t realize why until I almost got in trouble.”

Graffiti artists typically have a black book or piecebook where they practice tags with different art supplies. Black books can also be used to draft and plan larger pieces or murals. According to Cid, many artists within the community ask other artists to write or draw something in their black books in order to learn and improve from others’ styles.

“There are a couple of black books that have gone around the world and taken months to come back,” Cid said. “Different graffiti artists from different parts of the world fill in different blank pages, and then it eventually comes back to the original owner of the black book. Black books are really interesting because you can see a bunch of different styles, but mine were mostly just self-practice.”

Most graffiti artists operate in crews in order to complete larger pieces. While Cid wasn’t a part of any crew in particular, he would go out with his friends and other graffiti artists to put up graffiti. Since he was always interested in art and drawing, Cid would be in charge of drawing outlines and characters, while the rest of his friends would be in charge of more technical things, like filling things in with can control.

“We would always put the word or number one whenever we wrote stuff so that other people could tell we weren’t a part of another crew,” Cid said. “Usually, when you’re part of a crew, you’ll write your name or tag, then the crew name, so everybody knows what group you’re in.”

While there are no definite principles for graffiti, many graffiti artists abide by a particular set of unspoken rules. Most graffiti artists also tend to be reluctant to share their insights into the graffiti community online for fear of entanglement with law enforcement.

When graffiti artists prepare to put up their works, they are usually cautious of two major things: location and whether or not they cover up others’ works. If a graffiti artist put up their work in the wrong parts of town, they could be subject to arrest or worse, killed.

Before it became popular amongst youth in New York City, gangs dominated the graffiti scene. Gang graffiti appeared in the United States during the 1950s, according to Kan. Gang graffiti typically focuses on tagging to establish different gang territories within a certain area, and is facilitated by junior members of gangs.

According to Parmar and Bain, “gangs in the 1950s used graffiti for self-promotion, marking territorial boundaries, and as a method of intimidation.”

In many cases, covering up gang graffiti or putting up works of graffiti in gang territory can get you in lots of trouble.

“If you go into the wrong neighborhood, things can get really dangerous,” Cid said. “I remember when I was around 20 years old, I went back to one of the old neighborhoods I used to go to and started spray painting, then all these little gang member kids surrounded me and were about to beat me up.”

Cid emphasizes the importance of being aware of graffiti and gang activity around the city.

“We never did anything over gang graffiti, because we never wanted to mess with gangs,” Cid said. “We also wouldn’t paint over anything that we thought was awesome, or something that inspired us because by covering up someone else’s piece, you’re automatically starting a battle with them.”

Choosing a spot to put up graffiti can be challenging; depending on what type of graffiti a person might want to put up, different locations may be more suitable. If a graffiti artist just wanted to put up a quick tag, they could do it just about anywhere, out in the open. Tags tend to be quick, like signing a signature, and most taggers want their tag to be seen by the general public or other graffiti artists within a community.

For more intricate pieces, however, finding a suitable location can become more tricky. Graffiti artists want their works to be seen, but it’s difficult to avoid arrest while illegally putting up graffiti out in the open.

“Pieces” typically refer to more elaborate works that distinguish how different graffiti artists or writers express their imaginations, according to Kan. In many cases, pieces can be considered a form of social or political statement, as seen with works by viral graffiti artist Banksy, whose works are often laced with meaningful messages about the world.

The most common method of getting graffiti up into high places is by using climbing gear, Cid noted.

“People do crazy climbing stunts, and it’s really risky,” Cid said. “I was a scaredy cat, but I did do stuff in high places and climbed walls. It’s really risky and dangerous, but that’s part of the fun.”

Graffiti artists usually aim to find a location to put up their works where many people will see them. A large part of why graffiti artists vandalize public property comes from wanting a way to express themselves.

“It’s like having an outdoor gallery that’s free and accessible to anyone in neighborhoods that don’t have galleries or fancy art museums, and it allows people to have a voice and leave a mark, whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing,” Cid said.

In most cases, graffiti is considered an act of vandalism and is widely looked down upon. Street art, on the other hand, is an umbrella term that refers to any form of public art, such as murals or installations.

“It’s always going to be sort of a double-edged sword,” Cid said. “It’s not really graffiti unless it’s illegal, but then it’s essentially vandalism.”

Since its initial popularization, however, graffiti has slowly moved towards mainstream media, defying its original connotations of being a form of vandalism. As the style became more popularized, people began commissioning graffiti artists to create pieces on their property or on canvas.

“All these street artists just got way more involved in the mainstream art world,” Cid said. “A lot of people who started doing graffiti like Shephard Fairey moved more into gallery spaces, and their art slowly became more valuable over time.”

In the 1980s, the emergence of “wild style,” recognized by its heavily stylized lettering intertwined with icons and images from popular culture, triggered the golden age of graffiti, according to Kan. As graffiti wildstyle became more popular, many people began criticizing high art for being too institutionalized and intellectual. As a result, the public turned its eye towards graffiti.

“I think a great shift started with the Art Nouveau movement to annihilate the difference between ‘high art’ and ‘low art,’” Schulman said. “We have the classical art that is hung in museums, then you have the ‘low art.’ I don’t believe in a hierarchy of good art. It’s good art, whether it’s a quilt, a museum piece, or graffiti; it’s well-designed, well-thought-out, and well-done. Art is art.”

The walls of Schulman’s classroom are adorned with various forms of artwork: posters, stickers, works of students, and much more. Many of these artworks feature a graffiti art style, which Schulman teaches to her Art I class.

“In Art I, when I teach one-point and two-point perspective, I use a graffiti assignment so my students can learn how to do three-dimensional effects, instead of making them draw rooms or chairs, which would be boring,” Schulman said. “I want them to understand that graffiti art, and any art that involves letters, is very abstract. You have to learn a lot of artistic concepts to understand what makes good graffiti and what makes bad graffiti.”

As the focus of the art world shifted, graffiti entered the spotlight, and many graffiti artists became a part of the mainstream art world.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, otherwise known by his graffiti tag “SAMO,” gained lots of popularity within the art world before his premature death at 27 years old. Before he was known as an esteemed artist in the art world, however, he was a graffiti artist. His works are distinguished by the messages he conveys about race, power, class, and identity.

Around the same time period, Keith Haring’s works rose to popularity. Haring had a background in fine arts and adopted the graffiti art style upon becoming inspired by it during his time in New York. He later went on to become one of the most widely renowned graffiti artists, and his works are still held in high regard to this day.

As more artists like Basquiat, Haring, and Banksy entered the mainstream art world, the line between street art and graffiti became thin and blurry.

“I think the public perception of graffiti has changed a lot, especially from the early 90s,” Cid said. “Starting in the early 2000s or late 1990s in general, a lot of graffiti artists became more like Banksy and were more recognized by the regular art community, and they were asked to go into galleries or to create stuff on canvas.”

However, for some artists, graffiti’s shift towards mainstream media contradicted their original motive for getting into street art in the first place. As graffiti was adopted into mainstream art, many have taken more of an interest in its social, political, and artistic implications, completely ignoring the original culture and essence of graffiti, according to an article by Jennifer Lutz, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Duke University.

“When it hits mainstream, the culture gets diluted a bit, because a lot of the people who associate themselves with graffiti associate themselves with being outside of the system,” Schulman said. “Their original point was kind of being outsiders. I think it benefits graffiti as a whole, though, because the more people who see it, the more people can enjoy it.”

Cid shared a similar sentiment.

“If you have permission to do it on a wall and everything, it still feels like graffiti, but it’s not as scary even though you’re still out there in the elements and stuff,” Cid said. “I don’t know, there was just something really appealing about this unexpected, scary factor.”

Graffiti, at its core, is a crime of vandalism, no matter how artistic it is. According to the San Francisco Public Works website, it costs the city over $20 million each year to clean up graffiti.

“Graffiti is a crime that affects public and private property. It causes millions of dollars in unnecessary damage every year,” said Martin Ferreira, the graffiti abatement officer of the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD). “In order to maintain public trust, officers must recognize that graffiti vandalism not only affects individual property owners, but also entire communities.”

The main motivating factors preventing people from vandalizing public and private property are legal consequences. According to Ferreira, the consequences of graffiti may include arrest, fines, court-ordered community service, and payment of restitution to the property owner affected by the graffiti.

In addition, the California Legislature states that if the amount of damage caused to public or private property exceeds $400, it is considered a felon, and the perpetrator is subject to imprisonment by county jail for a maximum of one year.

“Around the early 1990s when that law was enforced, it really got me thinking. I loved graffiti, but I needed to stop because I could get myself into trouble and jeopardize the rest of my future at 13 years old; it didn’t make sense, and I didn’t want my parents to pay for all this damage,” Cid said.

Aside from legal consequences, business owners and cities have their own ways of combatting graffiti vandalism within communities.

“In Latino areas at liquor stores or just stores in general, they’d paint the sides of their buildings with images of the Virgen of Guadalupe or religious images so that people, including gang members, don’t graffiti over those,” Cid said. “It works pretty well, and I think people still do that. The police or another crew might not catch you, but it feels weird painting over the Virgin Mary.”

In many cities with prominent graffiti scenes, certain walls or streets are dedicated to street artists and murals. The city of San Francisco is littered with graffiti and murals, especially within the Mission District.

Among the Mission District’s vibrant murals and street art, the Clarion Alley Mural Project stands out as a community-driven initiative, transforming a narrow alley spanning one block into a dynamic canvas where artists express their ideas and stories.

“A lot of graffiti artists have moved more into getting permission and doing commission works on larger walls, and cities have also moved into creating safe spaces for graffiti artists to paint,” Cid said. “There are a bunch of alleys in San Francisco where you can just go and paint.”

As graffiti has evolved and gained recognition in mainstream media, many have grown to appreciate its artistic value and its role in enforcing culture within communities, according to Cid.

“I think people really need to understand that a lot of these people who do graffiti are really into it and are amazing artists,” Schulman said. “I want to see people open their minds to appreciate different forms of design in the world.”