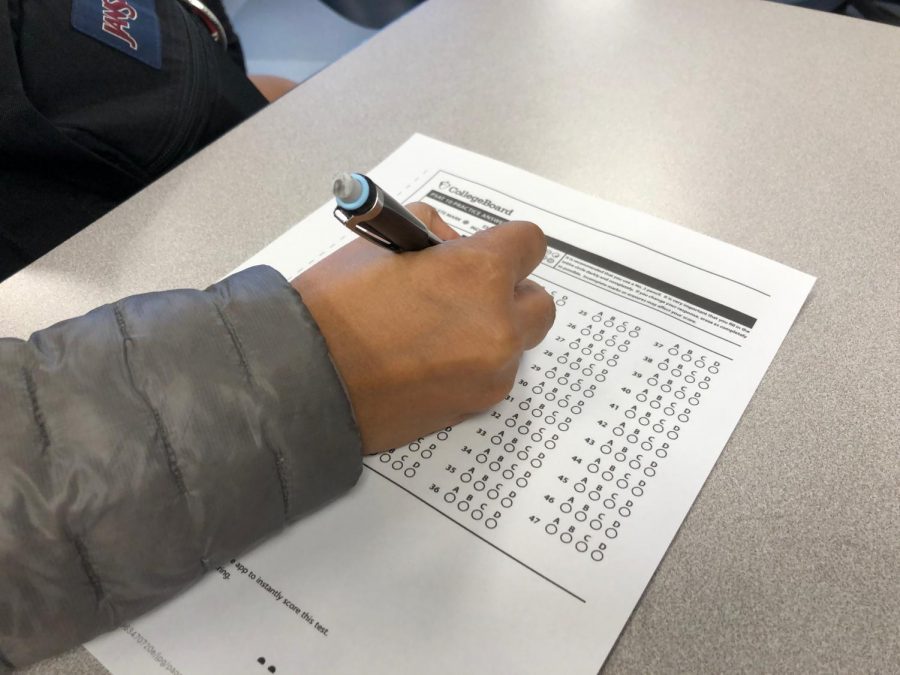

When taking the PSAT, many students check “yes” to opt-into the Student Search Service without really knowing what’s to come.

By checking that box, students’ information will then be sold to colleges and other nonprofit scholarship organizations.

However, some students feel pressured to share this information, even if they may not want to.

“I was warned not to check the box, but the people giving us the test made it seem like we had to,” said Aidan Dimick, a sophomore who recently took the PSAT.

Like Dimick, most students don’t get the chance to read or even look at most of the emails sent out by colleges. So, many are unaware that a portion of their data will be shared with colleges.

The information given away by the College Board is a lot more than one would expect at first glance. According to the College Board, they provide colleges with your address, major, assessment score range, GPA, gender, ethnicity, and your email for just 47 cents.

The College Board also sells access to enrollment planning services for around $7,000, which gives the user the ability to see information on the current classes in high school and the last five graduating classes. They can also research specific high schools and focus on “analyzing the competition.”

For another $17,750, one can have access to the Segment Analysis Service. This service allows users to have much more insight. Users can view a vast amount of information about recruited students. They can also target specific neighborhoods and, according to the College Board’s website, can “access individual cluster factor scores.”

The College Board sets “Organization Eligibility Requirements,” but these criteria do not solely include higher education organizations and scholarship organizations.

Right now, there isn’t any government mechanism for regulating people’s data, and the limited Obama era restrictions have been removed for quite some time.

The College Board has signed the student privacy pledge in which they committed to “not sell student personal information.” According to the College Board, they have a set of data privacy principles in which, “College Board does not sell student information; however, qualified colleges, universities, nonprofit scholarship services, and nonprofit educational organizations do pay a license fee to use this information.”

Furthermore, there has recently been a move to give people more control over their data.

“Data is owned by the people who collect it, and they’re allowed to do anything they want with it,” said Andrew Yang, 2020 presidential candidate.

Yang believes that these policies should change and that the data that belongs to each person should be protected and owned only by that person.

Some students may find these emails informative and feel that they do give insight to smaller and lesser-known colleges. Sophomore Jack Peacock says that he doesn’t find the emails particularly useful, but they do “bring attention to some otherwise unknown colleges.”

Other students, however, may feel that the emails do not serve a purpose, and some may not even be aware that they agreed to have their data shared. Kaimei Gescuk, a senior, says that she has no recollection of how she got on all of the email lists and that she finds them not at all useful.

Overall, the College Board gives access to people’s data to organizations without expressing specifically who gets the data or how that data is shared.