Like the beginning of a horror movie, another missing person’s poster is tacked against the wall. Along with thousands of Native women disappearing across the US, faces, stories, and memories are all families have left as we wait in uncertainty if these vanished women return.

Unfortunately, this isn’t just a horror movie. According to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center’s Missing Person Statistics, in 2020, there were 5,295 cases of missing women; 4,128 were under 18. The CDC reports that murder is the third leading cause of death for Native women between the ages of 1-19. Furthermore, Indian women are 2.5 times more likely to be raped than the rest of the country, according to an Urban Indian Health Institute report.

A Kansas University professor and attorney, Sarah Deer, suggests that many of these statistics are likely underestimated. American Indian women report less than half of all rapes and sexual assaults to law enforcement. Part of this is because they don’t believe law enforcement can make an impact on them.

“The United States has failed to protect Indigenous women on a legal perspective; it’s not just on perception,” said Dr. Lena Campagna, professor of sociology, “Look at the law. It’s right there.”

In the 1978 Supreme Court case, Oliphant v. Squamish Indian Tribe, the Supreme Court decided that “Indian tribal courts do not have inherent criminal jurisdiction to try and to punish non-Indians, and hence may not assume such jurisdiction unless specifically authorized to do so by Congress.”

“Tribes can’t do a whole lot,” said Lauren van Schilfgaarde, a UCLA research fellow. “So when there is a kidnapping or sex trafficking, or a drug crime or a murder on tribal lands, tribal police can have some authority, but they ultimately are relying upon either the state government or the federal government,”

However, state governments have frequently failed Native Women. Indian victims face high declination rates, and neither state nor federal governments choose to bring criminals to justice. Furthermore, on reservations, there is less law enforcement available, and it can be hard for them to obtain rape kits or seek medical attention directly after getting assaulted. Even when Native Women can get help, a legal mess surrounds tribal jurisdictions. Perpetrators can come onto tribal lands and commit crimes with a much lower chance of being caught.

“They [perpatrators] know that tribes can’t do anything about it, and the state isn’t going to care about Indian victims,” said Bree Black Horse, a senior litigation associate in the Native American Affairs practice group at Kilpatrick Townsend.

When states and federal governments do not catch criminals, pursuing perpetrators falls on Indian tribes. Tribes have some authority under the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act (VAWA 2013 and VAWA 2022). VAWA allows a tribe to have jurisdiction over non-Indians in cases of child violence, sexual violence, assault, sex trafficking, and assault of tribal personnel if the crime occurs within an Indian country to an American Indian.

But even if a tribe decides to exercise this power, it is incredibly complicated when Native law enforcement can get involved. It isn’t always certain what and who can be defined as Indian. These uncertainties make it challenging for tribes to exercise their power.

“Let’s say you’re a tribal police officer who gets called to a domestic security issue, and you might not be sure what the status of the land that you’re standing on is and who has jurisdiction over the parties involved. Then you might not know the Indian status of the perpetrator or the victim, and you might not be sure what exactly the crime is because some crimes can only be charged under state law, some only under federal law, and some only under tribal law,” Black Horse said. “It’s a mess.”

Knowing the legal status of land in reservations was complicated by The Dawes Act or General Allotment Act. It broke up Indian reservations in a push to westernize Indian people and make them all farmers. The government then sold the land to white settlers. A new concern for Indian people after their service in World War I led to the Indian Reorganization Act, which reinstated reservations. But this process left checkerboard reservations making courts unsure of who had authority in different sections of the reservation.

It is not so clear what it means to be Indian. It isn’t enough to have Indian parents; in many cases, one has to qualify under a blood quantum. Blood quantum laws mean to be eligible as Indian, one must have a certain amount of Indian blood. Some Native people can not qualify if their ancestors come from multiple different tribes or they are mixed race. Eventually, if this system continues, Native people will die out. That effect may be by design.

“Only three things in the United States are tracked by blood quantum: horses, dogs, Indians,” Black Horse said. “It’s not traditional that blood quantum requirement. It comes from the federal government and white policymakers.”

Policies constraining Native rights are not new; the US government swings between actively trying to end Indian culture or simply ignoring its existence. Since white settlers arrived in America, there have been constant attempts to irradicate Indians. In the mid-1900s, a push rose to end Native culture through boarding schools. The child welfare agency took Indians from their families and cultures and put them in white schools, believing they were saving kids from backward native society.

California is no exception to this trend either. During the Gold Rush, the California government sponsored a genocide that wiped out 80% of Native Californians in 20 years. According to History.com, our first governor assembled a massive militia to kill Indians.

The suppression of native people also takes form in the absurdly low level of engagement in crimes against Native people. Media biases and unequal reporting are significant contributors to this. Stories of assault towards Native people don’t sell the same way stories that perpetrate the stereotype of an innocent white victim do.

“The media likes to portray the ideal victim theory which, particularly with women, says that to gain sympathy from the public, the victim has to be white, victimized by someone they know, and look innocent,” Campagna said.

The media excluding Native people leads to widespread unawareness of missing Indian women and a general lack of knowledge about Indians. Some people don’t even know Indian tribes still exist in the US, much less the diverse range of Indian culture. Those who acknowledge Indian existence may have an old-fashioned idea of what entails a Native lifestyle.

“There is a big harm in thinking that indigenous people are supposed to look like x, y, and z, that there supposed to look like what we see in an old Disney movie,” Campagna said. “That’s where it becomes harmful, that’s where you’re putting someone in a box of being fictitious or completely misrepresented.”

Many Americans live without the knowledge that Native people are being victimized all around them. This lack of understanding causes Americans to participate in systematic injustices unknowingly.

The epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women that we are experiencing today is a direct result of 200 years of inconsistent internal racist and greedy policies. By the Feds and by the states.

— Black Horse

The effects of racist policies obliterate the relationship between Native women and the federal government. Indians aren’t given the means to protect themselves and are hesitant to ask their previous aggressors for help with their current issues. Broken trust comes with the countless broken treaties Indians endured.

“All of the markers of trauma are significantly present in most, if not all, tribes,” van Schilfgaarde said. “I think the missing and murdered indigenous person crisis is truly a symptom of a much larger crisis within tribal communities. It’s a result of centuries of harmful policies […] tribes are very much still reeling from the explicit efforts at eradication.”

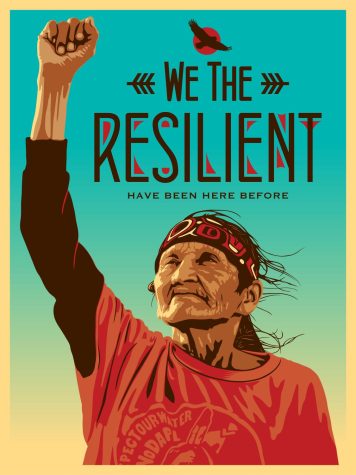

However, the trend of oppression is changing, and after 500 years of subjugation, Native people are finally starting to have a voice. On May 4, 2021, President Joe Biden issued a proclamation that supported solving missing and murdered cases: “My Administration is fully committed to working with Tribal Nations to address the disproportionately high number of missing or murdered Indigenous people.”

But the fight for Native women is far from over. There are many steps left to take. Our current system of tribal and nontribal interactions is failing to protect Native women.

“Tribal issues are best responded to by tribes, and so to the extent that we can empower tribal self-determination, that’s the route to success,” van Schilfgaarde said.

In California, there are currently 110 federally recognized tribes and 81 additional tribes seeking federal recognition. Indians make up a large portion of America, and their recognition and influence are growing. The movement to enable Indian tribes is growing. Partially because of reasons like this.

A political shift is occurring along with the increased attention this issue has. Continuing to unravel the multifaceted crisis of Indian subjugation is going to be quite a task. But to some, it is a necessary battle.

“Indian people, tribal nations, have always had to fight for what been ours and rights that we reserve. We’ve always had to fight for our lands, our natural resources, our children, all of it,” Black Horse said. “And that’s just how it is; we’re always going to have to fight.”