On March 8, Rachel Haurwitz, president and CEO of Caribou, gave a science lecture at Carlmont about CRISPR, the next big thing in the biotechnology department.

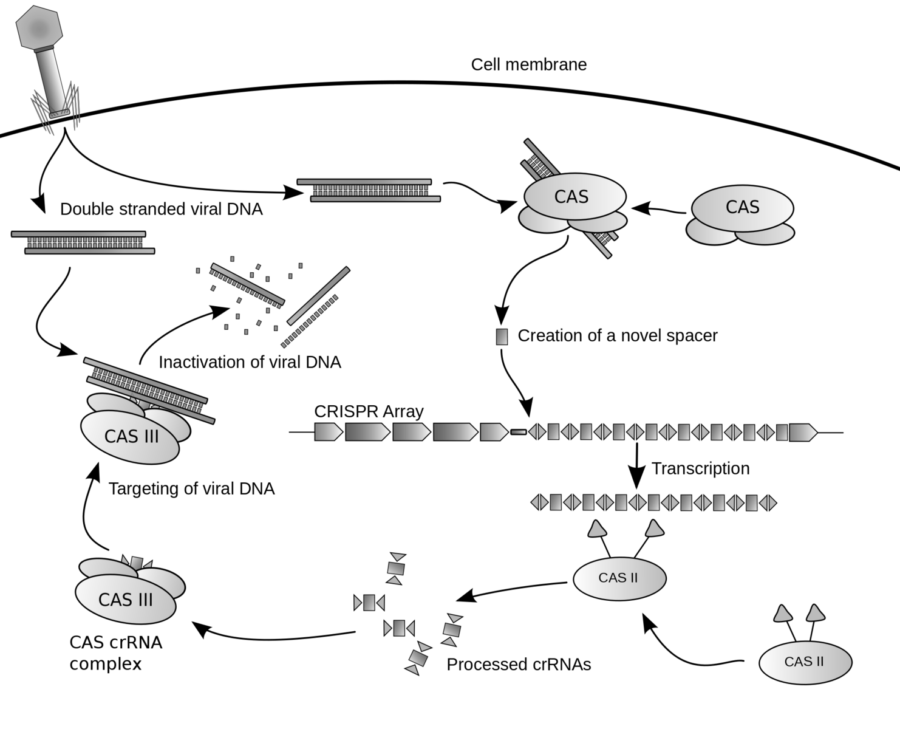

CRISPR, which stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, is a series of repeated DNA sequences found in the genomes of multiple species of bacteria and was discovered in 1987 by Yoshizumi Ishino. Years later, further studies found the reason for the existence of these sequences — bacteria are cutting up virus DNA and giving themselves genetic vaccines, building a fascinating immune system by using a precise-cutting protein Cas-9. Today, scientists have discovered how to program Cas-9 to cut any part of a genome they want, making genetic editing a lot simpler, faster, and cheaper.

With such a powerful tool in humanity’s hands, there’s a lot of potential to do good, but also to do evil.

On one side of the coin, CRISPR allows scientists to cut out DNA sequences which cause genetic diseases such as cancer and hemophilia, saving the lives of millions of people. In the span of a couple of years, humans would no longer have to know the horrors of the world’s most terrifying, incurable illnesses.

The technology could also be used to genetically modify plants and livestock to be more resistant to disease and harsh conditions such as drought, making it easier to feed Earth’s ever-growing human population. CRISPR has already been used to make pigs immune to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome.

On the other side of the coin, CRISPR could easily turn into a slippery slope. Genetically modified plants and animals are already a moral gray area, bringing up questions about humanity’s authority to modify the very fabric of life, and the editing of the human genome would make it even more ambiguous. While CRISPR technology could start as something used to help humans, it could turn into a tool for bettering humans as a species, with parents requesting their kids be taller, prettier, or stronger. CRISPR could lead to humans evolving themselves.

At the end of the day, no one seems to have a definite answer as to what is right and what is wrong, so America’s laws are a compromise between those who wish to use the Cas-9 technology on humans and those who do not wish to use it at all. While the cloning and genetic engineering of plants and animals are legal, the cloning of humans is strictly prohibited. While CRISPR could still legally be used to edit human embryos or the cells of a mature person, many teams of scientists have denounced the idea.

However, the U.S.’s somewhat stable, middle-ground approach on the issue will soon be challenged. On April 2015, scientists in China edited the human genome for the first time, showing that, despite it being an unstable method, it can be done.

With the quick progression of biotechnology and medicine, there is no doubt that similar experiments will follow all over the world as procedures become more stable, and it is inevitable that sooner or later someone will recreate them in the U.S.

America, as well as its citizens, need to start questioning where they stand on the issue of human DNA editing while they still have time to do so — a scientific revolution is just around the corner, and it will not wait for them to catch up.