For reasons I’ve never fully understood nor disclosed for fear of crucifixion in the sphere of county Democratic party politics, I sort of can’t stand Gavin Newsom.

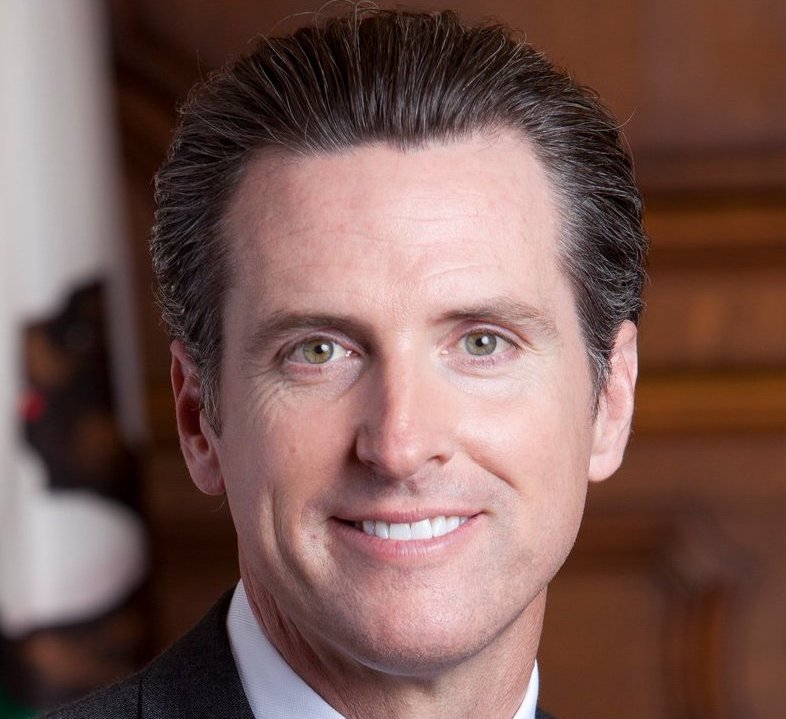

That might be understating it. I really do despise him. And I’m saying that as a dyed-in-the-wool capital D Democrat who tends to bow my head and toe the party line on these things. I’m not sure whether it’s the slicked-back inauthenticity, the supremely checkered past, the exploitative children-parading at campaign events, the sheer convenience of his region-appropriate progressivism, or that he looks like a ’60s pimp. I just don’t like the guy.

The catch here is that I’m having a hard time thinking of a non-superficial reason to dislike him. Every time I try to locate some sort of policy objection or area for legitimate concern over his future in the party, I’m left hemming and hawing for a bit until I arrive at the same basic conclusion: he’s a Mad Men caricature of a politician that I just can’t get excited about.

But being excited about a candidate is a gut feeling, ie something that varies from person to person, is intrinsic, and likely can’t be persuaded after the fact. It pains me to say that there might be more to Newsom than his oily mane and his wiry Gothamesque figure.

Not too long ago Trump appraised the State of our Union. That’s only appropriate to mention because Newsom’s name has been floated a few times as a potential Democratic candidate come 2020. I’m not going to wade into a dissection of who or what the Democrats need to win — it’s still too early to prognosticate and I’m certainly not qualified to do it. I can only say this for certain: Newsom isn’t the answer.

For someone who looks like he entered politics the nanosecond he exited the womb, it might come as a surprise to learn that he actually spent most of the ’90s running a boutique winery called PlumpJack. His business partner was Gordon Getty, the literal real-life Gordon Gekko, and someone Newsom was able to connect with via his dad. Following Newsom’s political career soon reveals just how many of his successes have been enabled paternally.

For example: Newsom was appointed to the Board of Supervisors in 1997 by then-mayor Willie Brown after helping out with his mayoral campaign. But, as with most things politics, the exchange wasn’t quite as reciprocal as one might imagine — the Sacramento Bee reported in 2017 that Newsom was appointed to his supervisorial position in 1997 at the urging of his father, who was friends with John Burton. The implication here, of course, is that Newsom wasn’t appointed to his seat by virtue of his merits (or by merit of his virtues?) and that rather he was gifted it by his father. Not that political success isn’t contingent on connections — only that he hasn’t been electorally baptized yet, save for a couple kindergarten supervisorial races.

He is certainly not without his political achievements. Newsom gets a lot of praise for a 2004 decision he made as Mayor of San Francisco to allow same-sex couples to receive marriage licenses. It was indisputably a great step forward for progressivism and an important precedent for moralistic municipal challenges of federal authority. A lot of the present enthusiasm for sanctuary cities, I think, can be traced back to that decision. But here’s the thing: San Francisco has been far further left than the majority of the country for years. It was not a crippling political gamble in 2004 for him to get out ahead of gay marriage as an issue — even if the Bay’s consensus wasn’t fully there yet at the time.

So I guess that means Newsom is a good politician. He can tell which way the wind is blowing and does a good job playing the odds. But that doesn’t make him an effective leader — it means he’s spent his political career untested in what largely are friendly waters.

Nor does it invalidate the tonnage of personal baggage he carries with him. Lest we forget his brief marriage with Kimberly Guilfoyle, former Fox News matriarch and host of The View until her recent ouster following turbulent sexual harassment allegations (now dating Don Jr.!). Or his 2005 fling with the wife of his deputy chief of staff, which indiscretion occurred during his marriage to Guilfoyle. I can only imagine that his highly public decision to seek treatment for alcohol abuse was an attempt to sate the spotlight in the wake of his affair scandal, which broke in January 2007.

Again, this all amounts to one conclusion: Newsom is an adroit politician who knows PR and has branded himself somewhat successfully. But as someone who has spent a couple of summers staffing politicians and learning the political ropes, inasmuch as that’s possible for a high school student to do, it bothers me just how unabashed he is about his politicism. I do not know how else to phrase that.

What bothers me most is that I agree with him. He doesn’t like NIMBYs. He supported single-payer. He’s sort of pro-business but also has a history of progressive social stances. Yet even San Francisco progressives aren’t convinced, going so far as to call him conservative during his 2003 run for supervisor. The Sacramento Bee notes that his leanings have shifted a bit left now that the arena of national politics is coming into focus.

He also is an interesting contrast to the declared field of Democratic candidates. In a field of hip, new-world politicians, Gavin Newsom represents a slicked-back, cigar-chomping breed of politico that finally died in the ’90s. Even those who might once have fit that mold have studiously rebranded themselves into figures palatable to a new, far more populist America. There’s even a bit of nostalgic charm in his Mad Men ways. Take Biden. He’s ancient, but his PR people have given him an age equal to that of his hair and teeth (ie, much younger than the rest of his body.) Even more unorthodox Democratic candidates like Pete Buttigieg, whose main disparity between himself and the stereotypical politician is his sexuality, carry themselves in a way far more appealing to a brand new world. Yet Newsom still operates in a vacuum; the very embodiment of the state of Democratic party politics. In a room full of living people, Newsom feels like a cold, hard, plastic, inorganic clone.

We live in a time of political villains. Those we despise nowadays are pure antagonists; evil courses through their veins. Which, I think, is why Newsom is sort of a foreign concept, at least to me: his caveats are diffuse and scattershot, and when you examine any given part of the canvas individually he almost seems alright, thank you very much.

It’s when you zoom out and look at him in macro that the picture gets a bit more foreboding.

Sheila Ramirez • May 31, 2019 at 9:40 pm

Fantastic article. Balanced and very well written. Bravo. All the best to you.