Hidden narratives: individual realities of student drug dealing

Content Warning: This article includes mentions of narcotics and overdose.

*All student sources in this article have fake names in accordance with Carlmont Media’s Anonymous Sourcing Policy to preserve their anonymity and prevent any social and legal consequences.

In 2021, a Carlmont senior accidentally overdosed due to a drug laced with fentanyl. In 2022, a shooting near the Carlmont High School campus was later determined by authorities to originally have been a narcotic transaction. Last year, Carlmont’s Administrative Vice Principal, Grant Steunenberg, stated that a student had been found with a bag of narcotics on campus.

“There was a case where I found fentanyl on the student. In the course of a search, I found a metal container that I opened up — there was a small baggy, and then the small baggy had white powder — not knowing what it was, but knowing that it was a drug of some sort,” Steunenberg said.

While drug use is surrounded by many different perceptions, it is something that occurs often, whether on or off school grounds. No high school is immune to the consequences of adolescents using narcotics, and what often accompanies drug usage is drug dealing.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, “in 2019, about 22% of students from grades 9-12 reported illegal drugs were offered, sold, or given to them on school property.”

However, the Carlmont administration attempts to create a safe environment for their students, including monitoring the potential threats that follow drug dealing such as overdoses, fights, and other drug-related events.

Many high school campuses around the country find themselves facing the consequences of drug use. While many schools detail the adverse effects of using drugs, selling narcotics as a student dealer comes with its own set of deterring factors. In the face of potential suspension, fights, and a heavy moral implication, why do students start dealing in the first place, and how do they even get into it?

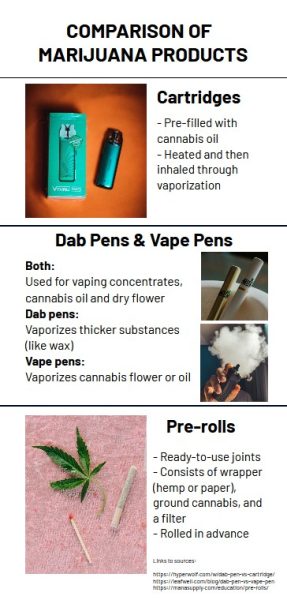

While there may be many reasons a high school student picks up drug dealing, it can come with a lot of risk. John Davis, a student at Redwood High School, originally started selling delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) vape cartridges at 10 years old. His environmental and personal reasons affected this ultimate decision.

“I started because I wanted money since I was too young to get a job. I wasn’t pressured, but my surroundings encouraged it,” Davis said.

Davis felt surrounded by an environment of people and businesses that promoted the use of drugs, which led him to ultimately decide this could be a path for him for now. Irrespective of the risk, high school drug dealers can turn to this for numerous reasons, many along the same lines of wanting extra cash.

“I just use dealing to help myself and my family, but it depends on your situation,” Davis said.

A single THC cartridge ranges in price from $10-$60, depending on the distributor. When Davis sells a box of these, which can contain 10 to 20 separate cartridges, he can make up to a profit of $120 per deal.

“Depends on how much you buy. Paying $180 to $200 for it, and then when you’re selling it, it is like $250 to $300,” Davis said.

Davis buys primarily from other dealers, which he describes as a network of dealers working together. While he can find them through peers, he knows of other dealers using social media to find their connections.

“Social media and technologies now, I guess kids are like messing around to find them,” Davis said.

While many student dealers help each other by looking out for one another, there are negative encounters with customers or other dealers.

These run-ins can be potential fights on or off school grounds and increase the overall risks of being a student dealer. Consequences also differ depending on these incidents. Additionally, if a student is caught dealing on or off campus, it changes depending on where they’re caught. The risk of getting caught can also involve possible suspension or expulsion if a student violates the education code.

“Schools work with the education code. So where it’s a law, they can enforce it, even though they’re not law enforcement, because it’s on school grounds. So they’re going to handle the school’s discipline side of it, and then we’re going to handle the legal side of it, and both of those can go congruent together at the same time,” said Belmont Police Corporal Brian Vogel.

Getting caught also depends on each situation and the particular student. Each student has a different reason for dealing, and the material they sell may also be different.

“Just depends on the person’s situation. Outside of school, that involves cops. Though depending on the school, you get suspended,” Davis said.

If someone is caught drug dealing, they face immediate consequences as well as possible future ones.

“If you get caught, it’ll be much harder to get a job after getting in trouble with the law, and it creates some personal and family issues, too,” Davis said. “Like my future job, I’m worried about my future in general.”

Despite the high risk and little reward, Davis feels trapped in an environment where he believes he no longer has a choice but to be a part of it.

“I’m stuck in a circle,” Davis said. “I say I’m still stuck in the circle because I don’t know how to get out of the situation.”

This “circle” can encompass a multitude of different personal or economic factors and contributions to why, even if Davis wanted to, it becomes much harder for him to leave.

“My environment is surrounded with sorts of people and a couple of stores; even some personal issues get in the way,” Davis said.

While he cannot escape this cycle, it remains vital to Davis that he is a reliable dealer and mindful of the people he sells to.

“I only give it to people that are already in it and that already like that stuff, but I make sure I check up on the people that I give it to,” Davis said.

In addition to being reliable, he has to establish credibility with his buyers to make sure they know he’s not selling them fake products, and he can avoid further issues.

“You have to know what you’re selling and know where you get it from. People will recognize it over time,” Davis said.

Many factors influence how a high school drug dealer is perceived and how they ultimately go about dealing at school amidst the threat of consequences, which is why Davis would like to eventually “go clean.” To other student dealers, he urges them to be cautious and safe.

Natural stimulants such as marijuana have been used by ancient Chinese, Greek, Indian, and Assyrian populations since as early as 2800 BC. These people primarily used marijuana for its therapeutic and psychiatric benefits, which is still seen in substance use today.

“I first started using weed last year from my ex. He sort of pressured me into it, and it helped a lot with my mental health, so then I started getting it from my brother, and I was looking around at other dealers and getting it,” said Carlmont student Mia Williams.

Williams later started selling marijuana to her friends, who also predominantly use it for its therapeutic benefits. Her reach has expanded, but she keeps her customer circle small.

“Usually the people I deal with are friends or friends of friends, it doesn’t branch out too much, so I can usually keep tabs on them a little bit,” Williams said. “I’m a very caring person, so if a person is coming to me a lot asking for weed or asking for alcohol, I usually ask what it’s for. If I’m worried about them, I’ll check in with their friends and then have their friends check in with them.”

With such a tight base, Williams has enough of a cover that her peers don’t often discover her marijuana business until they become close friends. Her front also prevents fighting with other student dealers, as most of them aren’t aware either. Additionally, Williams doesn’t sell marijuana for commercial purposes. Her motivation isn’t money.

“The people that have the most customers are the ones that have their customers extremely addicted,” Williams said. “Usually, addictions are because of mental health, and so it all starts from mental health, and then it increases. It really depends on the person.”

With marijuana legal in California, there are dozens of places in the Bay Area that sell it in a variety of forms. Undoubtedly, there will be stores that are lax in their identification policies. According to California Health and Safety Code Section 11361 HSC, selling marijuana to a minor is a felony and results in extended prison time. However, several businesses still look the other way.

“I buy from a smoke shop in [retracted] that doesn’t card at all. So as long as you look a little bit old, you get it easily, and they never card anyone unless you’re in a big group of people. And so I usually dress up a little bit older, and then it’s easy,” Williams said.

The title “drug dealer” often invokes an image of someone without a job, hoping to get customers addicted so they come back for more. However, there are multiple facets to dealing marijuana, and the situation is never a one-size-fits-all.

“I know a lot of people are scared to ask people they don’t know, and since I’m pretty innocent, in the sense of like I’m a 4.0 GPA student, an innocent little girl, people are more comfortable coming up to me,” Williams said. “The people that come up to me usually use it for their mental health. I’m more of a mental health dealer than a typical, ‘I just wanna be high all the time’ dealer.”

The driving factor for Carlmont students Charlie Thomas and Sam Martin to begin dealing vapes and marijuana was money. When they started, both were looking for extra cash on the side and an appealing status.

According to Thomas, he buys his vape stock from a store in the Bay Area. Since he went there often, he rarely was asked to show identification. However, he recognized the workers upcharged him for the products he’d buy from them.

“I know they upsell a lot of kids, and it’s just two old guys who work there,” Thomas said. “I don’t think it’s that hard; there are companies out there that will definitely help you.”

He purchases vapes for about $15 each and sells them for about $30. On average, a vape costs $8 to $12. Thomas started selling vapes as a side hustle but found there wasn’t much of a point because it didn’t make much money. Martin echoed that sentiment, claiming he “hasn’t fully stopped,” but it is easy money, nonetheless.

“Being a student dealer, it’s pretty easy for people to get into that. The type of kids that would have that thought pop up in their mind, it’s actually a common thing for people to do if they’re not trying to do it that widely. It can make them a little more money and help their friends out because I know a lot of people have tried and are doing it,” Thomas said.

Martin views his work selling vapes as a low-tier job. He claims that if he had a stable position elsewhere, he would stop dealing, especially since his customer base is mostly friends.

“I respect the hustle, but if you have a real job, you don’t have to deal,” Martin said.

Over 1,100 adolescents in the U.S. died from drug overdose in 2021. Of those, 884 deaths were related to fentanyl, over a 300% increase from 2019.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid often used in medical practice, kills quickly. Two milligrams are enough to kill an average adult. Due to its addictive nature and cheap manufacturing, some dealers lace other opioids, psychostimulants, and cocaine with fentanyl to cut costs and ensure constant business. However, their customers are not usually aware of the change. One pill may be fine, two can be deadly.

At the high school level, dealers have varying reasons for selling nicotine vapes and marijuana. However, most don’t deal with the intention of causing overdoses and understand the moral implications and the weight they carry by selling narcotics.

“I do feel a sense of responsibility for their health, and everything I am giving them could hurt them, but at the same point, it’s their choice, and they’re going to get it either way,” Williams said. “So I’m just giving it to them in a safe way where they’re not getting it another way that has fentanyl in it or from a person that’s really toxic.”

Thomas echoed a similar sentiment, claiming he ensures his merchandise is real and not laced with other opioids to protect his business.

“You can’t sell to a dead customer,” Thomas said.

High school users often aren’t purchasing narcotics in attempts to overdose as well. The main drivers of usage include social groups, experimentation, and mental health, according to the Indian Health Service. Thus, mutual trust is essential.

“I have to know you to get stuff from you. I don’t trust random dealers; it’s personal safety,” said Ava Miller, a student at Carlmont.

School discipline for possession of narcotics varies depending on the situation. According to Steunenberg, possession or influence of marijuana or alcohol results in confiscation, in-school suspension, and a conversation with parents. For the most part, these consequences would be in place if the student is found with marijuana or alcohol from the moment they leave their home in the morning to the moment they arrive back home from school.

A second offense would likely result in a longer suspension or the option to do drug and alcohol counseling. However, catching a student with narcotics or vapes is difficult for the administration.

“If I see a group of 10 guys in the bathroom, I’ve got to figure out reasonable suspicion in order to search them,” Steunenberg said. “When I walk in, there’s a bunch of people in there, so what? Nothing illegal about being a bunch of people. Seeing a plume of smoke, or seeing someone breathe it out, or I see the haze in there, provides me with enough reasonable suspicion to bring them in and search.”

According to Steunenberg, the Carlmont administration errs on the side of caution regarding reasonable suspicion to search a student. They violate the student’s rights and could lose their job if they don’t have enough reason to search.

“If we catch a group of people in the bathroom, we’re pretty sure we know what they were doing,” Steunenberg said. “If we don’t have that reasonable suspicion, we’re gonna let them go because, more than likely, they’re gonna do it another day, and at some point, we’ll catch them.”

For the most part, narcotic-related incidences on school grounds will be handled by both the Carlmont administration and law enforcement. According to Vogel, both academic discipline and criminal justice proceed congruent in cases where the police are involved.

“We’re going to kind of look at the totality of the circumstances to determine whether criminal charges are appropriate and make an arrest, or maybe school discipline is enough or school and parent discipline,” Vogel said. “Generally, anything we try doing, we’re going to make it go through the criminal justice system. That way, there’s some accountability rather than just a warning.”

Even with various academic and judicial punishments for getting caught and the weight of others’ lives on their shoulders, some high school students still sell narcotics. Statistics of narcotic overdoses and fentanyl deaths make it easy to view all dealers as heartless criminals who would do anything for extra cash. At the end of the day though, they’re all humans, too.

“Most of the student dealers I know are good people,” Martin said. “People think drug dealers are evil people and stuff, but that’s not the reality.”

Resources:

California Drug Abuse Hotline: 844-289-0879

Caifornia Addiction Hotline: 866-210-1303