Humans get distracted.

Among the many things we get distracted by is shocking news.

It makes sense: Why would we care about mundane stories when there are more exciting events occurring? The news is going to report on major stories, not everyday life. Whether we like it or not, the news that’s published will always be sensationalized.

It boils down to “dog bites man” versus “man bites dog” stories. One of these, “dog bites man” is an everyday occurrence, while the other, “man bites dog,” is rare. Car crashes are a great example of this. A single accident is an example of a “dog bites man” scenario, one of 6 million accidents every year in the U.S. On the other hand, the 69-vehicle crash in Virginia in Dec. 2019 is an example of a “man bites dog.” The “man bites dog” scenario is more frequently reported on, while the “dog bites man” is often not.

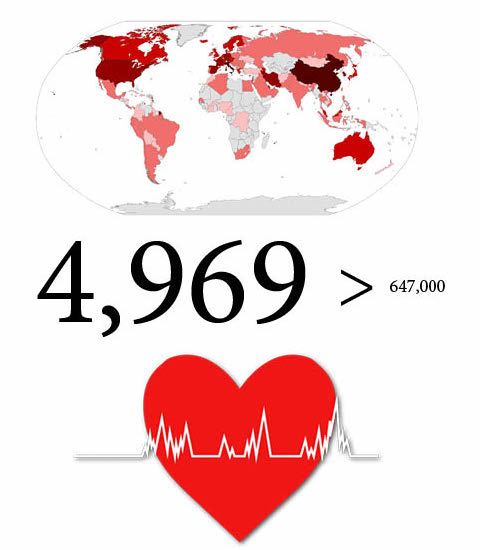

The same can be applied when it comes to COVID-19; it’s reported on 24/7 in part because of how major it is. During this outbreak, I’ve seen tweets asking why people care about COVID-19 when there are much larger greater causes of death. Even though COVID-19 kills much fewer people than heart disease, it’s definitely more newsworthy.

For one, it is affecting the world, both directly through individual cases and indirectly through the economy. Also, the deaths caused by heart disease, being much more common, are overall less interesting to most people. Most importantly, we have less control over COVID-19.

In “Freakonomics,” authors Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner touch on how we assess risk, which is similar to newsworthiness. Levitt and Dubner use the example of terrorist attacks and heart disease to demonstrate how humans determine risk.

“The likelihood of any given person being killed in a terrorist attack is far smaller than the likelihood that the same person will clog up his arteries with fatty food and die of heart disease. But a terrorist attack happens now; death by heart disease is some distant, quiet catastrophe,” they wrote.

Although risk does not directly translate to newsworthiness, the events that are perceived as a greater danger are often published more. Even if something isn’t statistically more dangerous, the fear of the immediate outweighs the fear of the distant. This leads to more news surrounding immediate threats, such as COVID-19, as opposed to distant heart disease.

The sensationalization of news is neither inherently good nor bad. The nature of media means that significant events from around the world are heard, as opposed to smaller, more local events. However, the events that are deemed newsworthy are, for the most part, negative. Whether we like it or not, news has been and always will be sensationalized to draw our attention.