Beneath our community, there lies a dirty secret. It’s dirt.

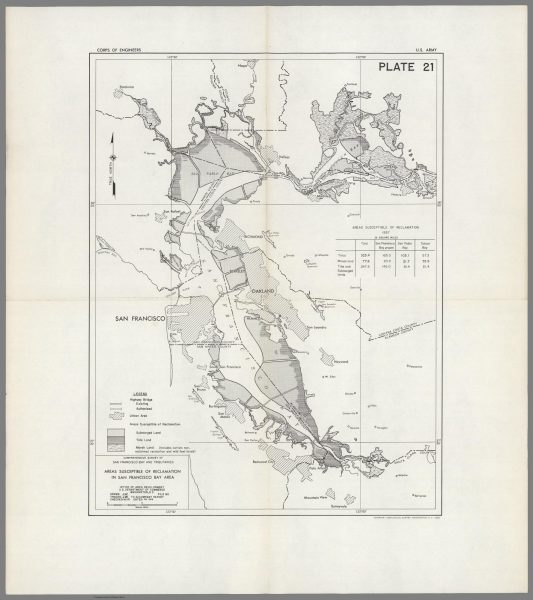

There are 243 square miles of bay fill in the San Francisco Bay Area. Bay fill, also known as land reclamation, is the process by which coastal marshland or shallow water is filled in with some substance often concrete or heavy rock before the gaps are filled with dirt or clay.

Marshland is filled in with earth and developed. Originally done to expand the available land, the consequences of paving over a key part of the ecosystem are still present.

The Bay Area marshland is a crucial part of the ecosystem, with many working to protect the endangered areas that remain.

Starting in 1850, 90% of the original marshland was developed according to the National Park Service. Developments ate away at the edges of the bay, slowly destroying the once incredible natural beauty. That was until people began to take notice.

In 1959, the Army Corp of Engineers released a report titled “Future Development of the San Francisco Bay Area, 1960-2020” which revealed how land could continue to be reclaimed bringing the water source to a fraction of its original size.

An image of what the Bay could become was published in the Oakland Tribune which served as a catalyst that caught the attention of many residents.

Three of those residents, Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr, and Esther Gulick would go on to create an organization called Save the Bay.

Led by Save the Bay, residents worked to lobby the government to preserve the San Francisco Bay.

Eventually, in 1965, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission was founded to protect the San Francisco Bay and advance responsible use of the Bay. The commission continues protecting the salt marshes, the marsh environment that gets flooded and drained by ocean tides, to this day.

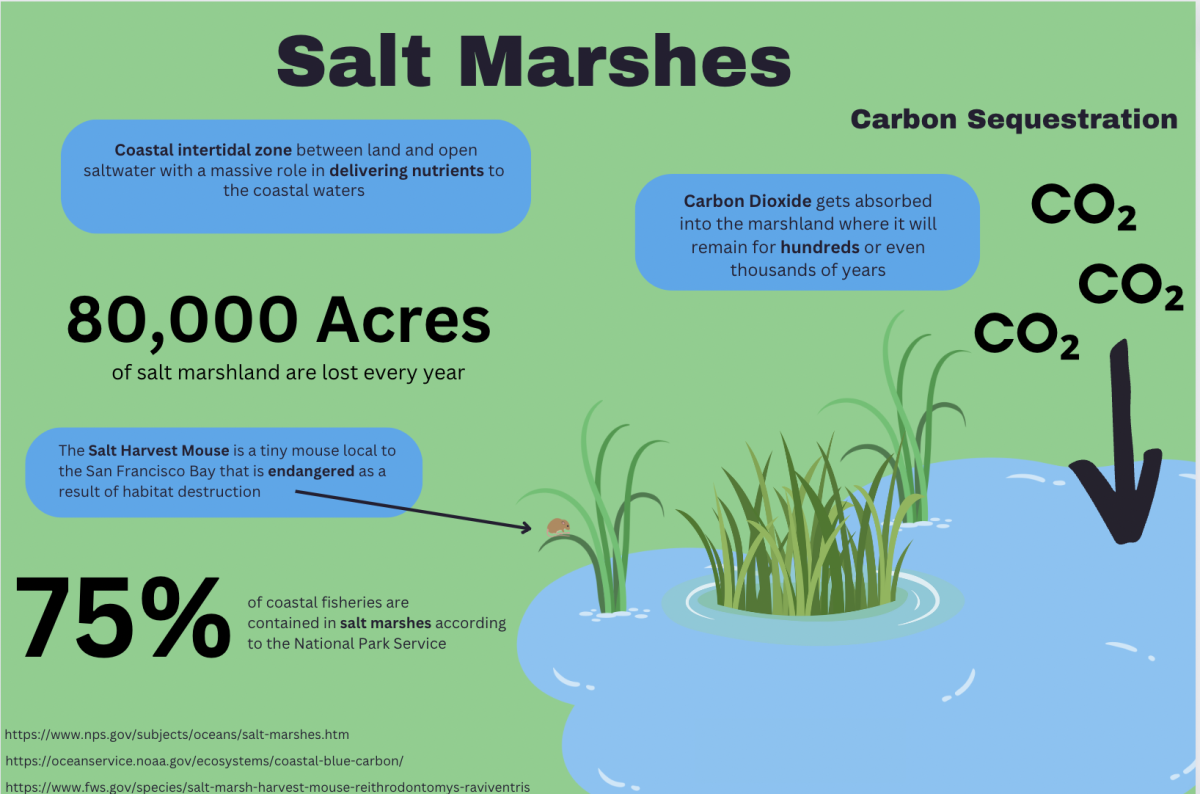

According to the National Park Service website, “salt marshes are the ecological guardians of the coast.”

Containing 75% of fisheries species according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, salt marshes provide an essential habitat for the ecosystem. The absence of the original 90% of the marshland pushes many local species to the edge in search of help.

“Laws, policy, and government funding dictate what kind of restoration work can be done,” said Hayley Currier, a member of Save the Bay’s advocacy team.

Save the Bay continues to operate with the goals of advocacy, restoration, and education.

Advocacy is an essential part of the organization’s work changing the systems around us to help protect the environment we all share.

“We build relationships with other organizations, elected officials, and government staff people in order to build pressure on decision-makers for laws that better protect the Bay,” Currier said.

Through advocacy with different groups, restoration areas can be obtained, helping fulfill Save the Bay’s namesake.

“Most of the developments are bought by the government or come from private donors,” said Meg Kikkeri, another member of Save the Bay.

The restoration process adds back to the small amount of remaining marshland, strengthening the entire ecosystem. However, restoration takes time with many projects spanning over years.

“We have two-year planning stages before even going out on the site,” Kikkeri said.

They also grow their own native plants to use which can take a month of careful management. When Save the Bay does go to plant native species, they use public programs on Saturdays to massively increase their productivity.

“We would not be able to get a lot of our work done without community support,” Kikkeri said, “Thirty people working for two hours goes by much quicker than five working for eight hours.”

While the organization benefits from the volunteers, the volunteers also gain from the organization.

“It’s fun to volunteer and go out on the bay and weed invasive plants and plant native plants,” said Jamison Elliot, a Bay area resident volunteering with Save the Bay.

As well as getting enjoyment from working with nature, volunteers also get to see a change for the better in the environment.

“Every little thing that someone does helps,” Elliot said.

Different groups and individuals are always working to protect the environment

While slyly, things continue to seep beneath the gaze of most.

More than 7 trillion microplastics move from city streets to the San Francisco Bay each year according to a San Francisco Estuary Institute study. Microplastics are plastic particles less than five millimeters in length according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Bay fill serves as an excellent entry point for pollution as a result of the site’s nature of being on top of what was part of the bay’s tidal cycle damaging the bay as a whole. But Bay Fill is not alone in that regard.

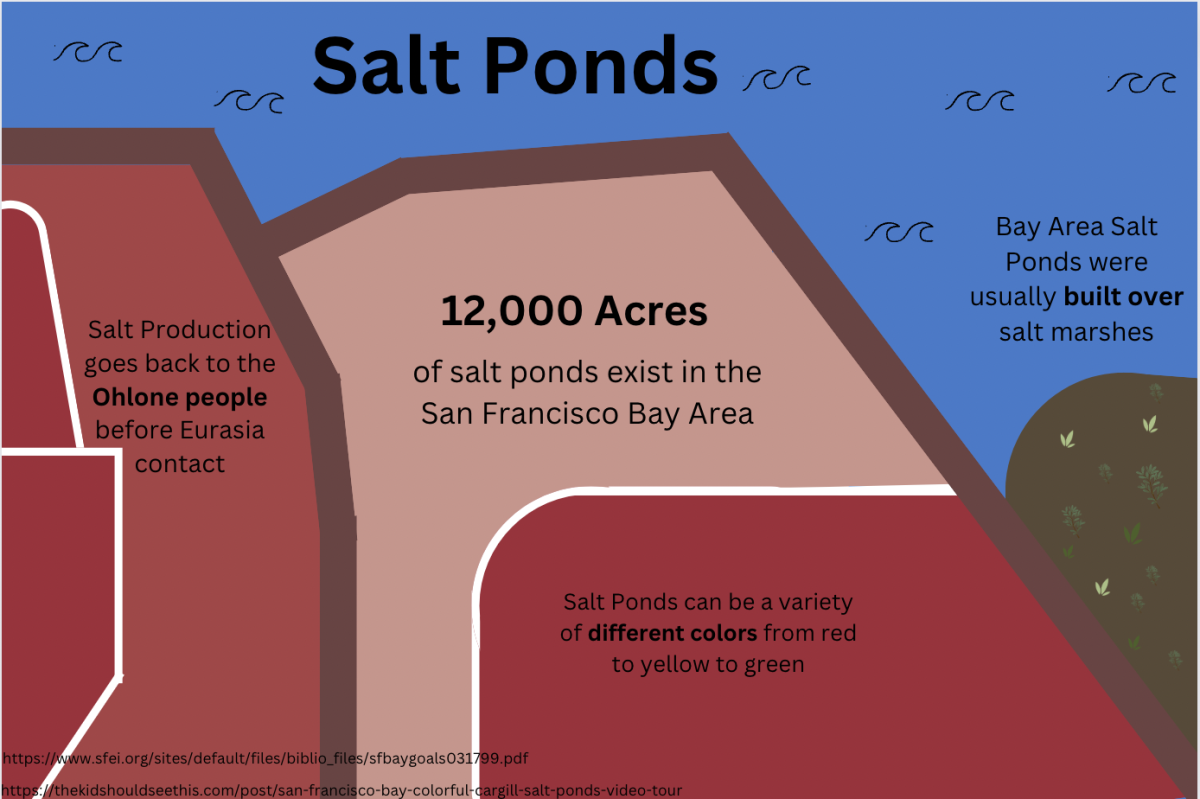

“Salt ponds hurt the bay through their varying salinity,” Kikkeri said.

A salt pond, which is different from a salt marsh, is an artificial pool of salt water that is then left to evaporate from sunlight leaving behind salt. The salt is collected and sold for a profit. While being profitable, salt ponds that were created in the bay were made on top of marshland destroying the environment.

The excess salt from the pond can seep out into the bay varying the salinity level drastically hurting the entire ecosystem in the process of evaporation.

While salt pond’s benefits can be easy to dismiss, bay fill’s can be much more difficult to eliminate.

“Without the bay fill being built here I won’t be living here,” said Michael Nishikawa, a lifelong Redwood Shores resident.

Redwood Shores was originally marshland that was filled in during the 1960s to develop new housing real estate. The value of which is higher than ever with home prices reaching all-time highs, the average home price in Redwood Shores is $2 million according to RedFin. Without the additional real estate home prices in the area would only be higher.

Only a small amount of the marshland was spared in the development and even it has immense value.

“It is nice to see the nature and birds that are left,” Nishikawa said. “When I was younger, my neighborhood would get together and we would look out over the water.”

The nature that provides for all will not be around forever. The majority of marshland could wash away by 2110 as a result of sea level rise from climate change according to a 2011 report. This means that the marshland spared from the seizing of land reclamation needs more help than ever.

“It’s gonna take a lot of behavior change, a lot of infrastructure change, and a lot of political change to protect the Bay,” Kikkeri said.