The retreat of the Thwaites Glacier is accelerating sea level rise at a rapid rate.

Located in the Western Antarctic, the collapse of the Thwaites Glacier, which is larger than the size of Florida, will cause alarming increases in sea level rise.

The Thwaites Glacier was coined the “Doomsday Glacier” by New York Times best-selling author and Rolling Stones contributing writer Jeff Goodell in 2017. According to a study by the Nature Journal, the glacier is shown to be “susceptible to rapid and irreversible ice loss.”

“The Thwaites Glacier is, like scientists describe it, as a cork in a wine bottle that would hold back the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet. So if Thwaites collapses, then the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet is in trouble,” Goodell said.

The Thwaites Glacier is part of the larger Antarctic ice sheet, one of the many ice sheets in the world.

“When you think about ice around the world, we glaciologists usually divide Earth’s ice into three categories,” said Dr. Twila Moon, the Deputy Lead Scientist and Science Communication Liaison at the National Snow and Ice Data Center. “There’s the Antarctic ice sheet, which is a continent, the Greenland ice sheet, and all other ice sheets. Right now, the West Antarctic ice sheet, particularly the Thwaites Glacier, is melting,” Moon said.

The Thwaites Glacier is melting much faster and is happening unevenly in the Western Antarctic, according to Tran.

“The West side of Antarctica has relatively warmer ocean water – that’s why it is melting faster, but also because the West side is much thinner. If you have colder ocean water, the temperature profile changes gradually,” said Kiera Tran, a PhD student at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Geophysical Glaciology.

“Melt rays can happen in various ranges inside just one ice shelf. It doesn’t happen uniformly. It’s really based on the ocean’s water temperatures and salinity out there, and also the flow of the glaciers from the inland and how it interacts with the bathymetry,” Tran said.

The melting of ice sheets leads to sea level rise due to how glaciers are formed. According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center, glaciers begin to form when snow remains in the same area year-round, where enough snow accumulates to transform into ice.

“Polar ice sheets store freshwater on land, in the form of ice. If that ice starts to melt, meltwater is transferred from the land into the ocean. With more water to fit into the oceans, the consequence is sea level rise,” said Professor Adam Booth, a Co-Investigator in the Thwaites Interdisciplinary Margin Evolution for the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration.

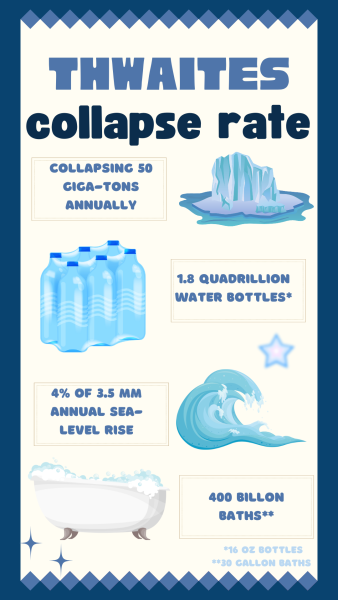

Thwaites, in particular, is collapsing at an urgent rate, according to Tran. The mass loss of the Thwaites Glacier over the years is accelerating, according to a study from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We know it’s unstable and we know that it’s beginning to collapse, but how long that will take, whether it’s 10 years or 50 years, is still unclear,” Goodell said.

“A large part of ice in West Antarctica flows out through the Thwaites Glacier, which acts sort of like a plug to the upstream ice. The stability of Thwaites has important repercussions for a large part of the West Antarctic ice sheet,” said Michalea King, a Polar Science Center Senior Research Scientist from the University of Washington.

“There are a number of so-called geoengineering solutions to try to mitigate the Thwaites Glacier melt, but these are unproven technologies. The sheer scale of the Thwaites Glacier, which is bigger than the state of Florida, means that they are very challenging to implement. They also don’t address the main issue of needing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow the effects of climate warming. For me, this is the most urgent intervention that we need,” Booth said.

There is a lot of research to be done in the West Antarctic is costly, according to King.

“These ideas are all highly costly, require a lot of materials and likely waste, and still have unknown impacts on the environment and local ecology. The huge scale of the Thwaites Glacier poses immense challenges for geoengineering-related mitigation strategies,” King said.

“There are several ‘moon shot’ ideas for mitigation near Thwaites. These ideas are mainly focused on either helping to pin or stabilize parts of the glacier in an effort to slow down glacier flow or blocking warm ocean water from reaching the front of the glacier where it is most sensitive to retreat,” King said.

There are also other ideas that target climate change in general.

In 2017, Goodell came across a recently published paper that talked about the increasing scientific concerns about the possible collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. He started talking to other scientists, did some reporting, and realized the dangers that it poses to virtually every coastal city in the world.

“I wrote a long story for the ‘Rolling Stone’ about this and I just came up with the phrase ‘Doomsday Glacier’ as an evocative title for the story, which I think has captured the large-scale risks that the melt of this glacier poses,” Goodell said.

The collapse of the Thwaites Glacier would lead to a 25-inch sea level rise, according to a Nature Geoscience study. Coastal states in the United States such as California, Florida, New York, and Texas would have many coastal cities flooded, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

It’s not only coastal residents that will be affected by sea level rise.

“Local people might run into issues with drinking water, sewage systems, or flooding and things like that, but people who live far from the ocean might still be connected to those impacts because you have disruptions in your goods or services,” Moon said.

Moon suggests a way of thinking called multi-solving, in which solving one problem effectively resolves multiple others.

“I think for people who maybe aren’t particularly concerned about climate, they might be interested in their pocketbooks or they might be interested in having homes or business buildings that are really comfortable to be in. We can clean up air pollution, and that is a win for the planet, but it’s also a win for our health. And many people might care more about short-term health than they care about climate,” Moon said.

Despite possible significant impacts of the Thwaites Glacier collapse, humans are not “doomed.”

“This is scary, but there’s a lot we can do to fight for it and make a better world. I actually think that this is an opportunity to really build a better world because we are going to reinvent our energy system. We are going to reinvent where we grow our food. We are going to reinvent how we build cities. We just need to do it fast and we need to do it smart,” Goodell said.

Every step to help mitigate the effects of climate change is an important step, according to Goodell.

“There is no tipping point, there is no place, there’s no moment when we’ve lost or won. It’s not like a coin flip or a binary or something like that. Even if we keep warming to where we are right now, it is better than warming two more degrees,” Goodell said.

Constantly pushing for better standards in our climate is shown to be effective, according to the Climate Action Tracker.

“This idea that there’s a moment when it’s all lost is very damaging and not true. I find it endlessly inspiring and actually not that scary and doomy because I meet so many people who are fighting so hard for a better world,” Goodell said.