Riots in the street.

A divided government that can’t pass any legislation.

The previous president refusing to give up office.

These are the stories many are telling. America divided like never before, an era comparable to the American Civil War according to experts like Presidential Historian Michael Beschloss.

What’s worse is that these claims appear to be true. Biden won only 51% of the popular vote, and Trump managed to win 47% — a very close margin.

Both liberals and conservatives have protested despite the COVID-19 pandemic, and the rhetoric between people of the opposing parties seems to be worse than ever before.

This is how the U.S. looks to the public, but appearances can be deceiving.

Only one president in history has managed to win 100% of the electoral votes: George Washington.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, even Thomas Jefferson and FDR couldn’t get all of the states to vote for them.

That’s not even to mention the popular vote, which is far more telling of the population, and most of the time, far more divided than the electoral college.

Encyclopedia Britannica also noted that the majority of presidents have only gotten between 50% and 60% of the popular vote.

Only six presidents have gotten above 60% of the vote, while 19 presidents have gotten below 50%.

The lowest recorded popular vote of the victor is John Quincy Adams in 1824, who won only 30% of the vote and was voted into office by the Senate.

Even presidents like FDR, who won 98.5% of the electoral college in 1936, only received about 61% of the popular vote.

So America has always been divided. While the divisiveness of modern politics, social media, and the internet may exacerbate the divide, they are not the cause. What, then, is the link tying America’s history of division together?

Some 224 years ago, one man answered this question. In his Farewell Address in 1796, George Washington addressed this matter, even though the problem he answered did not explicitly exist in America yet.

“It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection,” Washington said.

Washington was talking about political parties.

At that time, there were the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. They were two parties that held opposite views on the structure of government the U.S. should take, and it was almost impossible for them to get along, agree, or concede anything.

Party politics have existed since America’s founding. Even before they gained names in the 1790s, they existed in the form of the southern states vs the northern states.

As time passed, more parties formed and gained names, such as the Federalist and Anti-Federalist parties, the Whig Party, and the current Democratic and Republican parties.

While many parties were created, few managed to gain enough votes to truly be considered a party. Most elections were contests between two main parties, like today’s elections.

Over the years, an ever-deepening gap between the followers of whatever the two major parties are has formed.

The effect is even worse now because the Democratic Party has existed for 192 years, and the Republican party has existed for 164. The party name recognition and bases are more powerful and concentrated than ever.

Could this mean that people are more aware of what they want?

In the eyes of Karen Ramroth, teacher of government and ethics at Carlmont High School, this isn’t the case.

“Voters don’t have time to research policies and candidates and simply rely upon who has a ‘D’ or an ‘R’ by their name to make their political choices,” Ramroth said.

What Ramroth is suggesting is that the voters aren’t well informed. Instead, they continue to vote based on party affiliation.

There are a variety of other factors that also influence people’s opinions. Race, gender, age, education, and religion are significant factors.

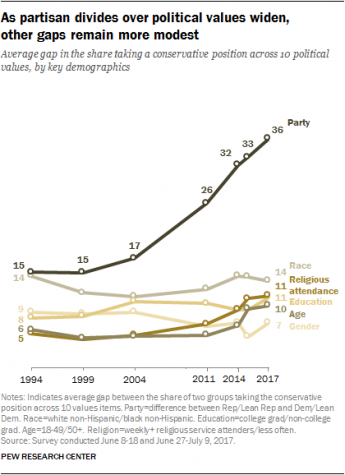

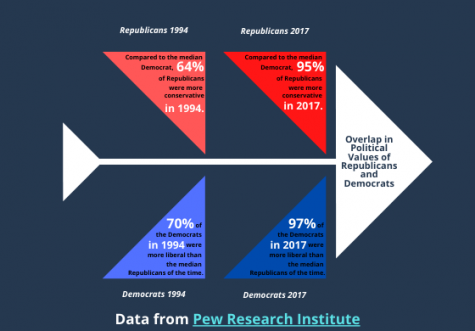

However, Pew Research Center’s study heavily supports that party affiliation is the main factor in differences in political ideology.

“Two decades ago, the average partisan differences on these items were only somewhat wider than differences by religious attendance or educational attainment and about as wide as the differences between blacks and whites. Today, the party divide is much wider than any of these demographic differences,” Pew Research Center said.

The gap between the parties came into existence when Americans separated themselves into parties. However, Pew asserts that the impact of the parties on the mentality of people has started to increase recently.

Specifically, the political party’s influence on the change of political ideology started increasing after 1999.

An example would be the Democratic party accepting homosexuality more openly and Democratic voters who may not have supported homosexuality changing their stance.

The most likely event to have increased the impact of political parties is the creation of the internet, social media, and the first cheap, widespread smartphones, which all occurred in the 1990s.

This is hardly surprising. Widespread convenient access to politicians’ opinions make the spread of party ideals and divisiveness far easier.

This spread has been achieved through two primary means: the media and social media platforms.

De Anza College’s Professor of Political Science Jim Nguyen highlights the media as a major issue.

“There is a middle in this country, and it’s just that is not the voice we’re hearing. It gets drowned out by what’s presented in the media,” Nguyen said.

Nguyen reveals a fundamental fact about reporting: the goal is to get a story. And the middle is scarcely as dramatic as the extreme.

The middle also tends to be quieter. Those at the extremes are always less willing to compromise and more willing to make a fuss about it. The dispute creates controversy, which attracts the media.

The extremes don’t only impact people through the controversy of their opinions. They also share their lack of willingness to compromise.

Additionally, those with extreme beliefs often dislike their opposition more than those with less extreme views do.

Stanford professor Shanto Iyengar concludes that people who support those with extreme beliefs also tend to dislike the opposition in his paper Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization.

“Using data from a variety of sources, we demonstrate that both Republicans and Democrats increasingly dislike, even loathe, their opponents,” Iyengar said.

Iyengar also proposes that this loathing causes an increase in the parties’ divide. The dislike, which is worsened by both parties’ rhetoric and their supporters, only continues to worsen.

The difficulty is figuring out how to rid America of the distrust of the opposing party. Reducing the animosity is also essential to solving the current divide between the parties so that compromise can be possible.

Many may wonder, how can Americans bridge the gap?

There are a few methods, both intentional and unintentional. The three main ones are suffering through a major crisis like a war or a depression, having politicians who use rhetoric to unite the people or improve their base education.

“Either, God forbid, there’s a crisis— you wouldn’t want a civil war or an external crisis, like World War II and the threat of Hitler and the imperial Japanese, that caused Americans to resolve their differences and fight the war—or you have a president who says, part of my job is to bring people together,” Presidential Historian Michael Beschloss said.