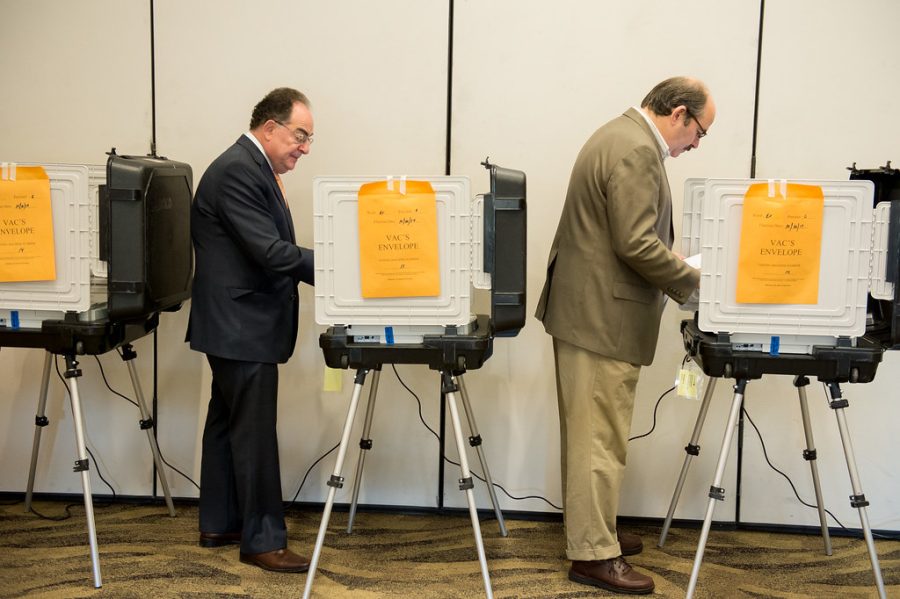

The United States is a proud beacon of freedom, of justice, of democracy. We wave our flag high and proud, especially come election time. And when you’ve walked out of that poll booth, donning your “I voted” sticker, you participate in a democracy that boasts itself as the best in the world.

For the millions of incarcerated Americans, this comes as a slap in the face. About 4.6 million Americans were denied the right to vote in 2022, according to The Sentencing Project.

This may seem surprising, considering Trop v. Dulles (1958), a Supreme Court case in which the justices decided that prisoners’ citizenship cannot be suspended for committing a crime. The arguments laid claim to the 8th Amendment; suspending citizenship lies under cruel and unusual penal remedies.

Denying citizens the right to vote violates the very concept this decision was based upon. While prisoners keep their badge of citizenship, they aren’t really given the same privileges as any other citizen. They’re disenfranchised — suspended the rights promised to free citizens.

This creates a new group: one bound by the laws and restrictions of the U.S. but restricted from participation. The opposite of what citizenship is meant to be.

It gets worse. The term “prison-based gerrymandering” describes the inclusion of prisoners’ population in the legislative district of their prison. Simply put, even though these prisoners aren’t allowed to vote, they’re used as numbers for state representation.

If this sounds familiar, it may be because it’s reminiscent of the Three-Fifths Compromise. Before abolition, slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person for population purposes — in any other situation, they were considered property.

Even in 1920, when both Black men and women finally secured the right to vote, the fight for voting rights wasn’t over. Jim Crow laws still raged hard, instating themselves in the form of intimidation, poll taxes, and literacy tests. Our nation still struggles with voter suppression, and restrictions on prisoners are no help.

Black Americans are disproportionately affected adversely by our justice system. Despite only constituting 13.6% of the U.S. populace, Black inmates comprise 38.4% of the prison population. And, one in every 19 Black Americans of voting age is disenfranchised.

This is just another method of Black voter suppression.

It doesn’t end with the sentences, either. According to a 2019 Campaign Legal Center and Georgetown Law’s Civil Rights Clinic report, 30 states disenfranchise some felons based on wealth. Essentially, released felons cannot recover their right to vote without paying some sort of fines or fees, depending on the individual state. These are glorified forms of poll taxes.

The time is done, and the punishment is complete. But the right to vote still isn’t restored.

Only in Maine, Vermont, and the District of Columbia do prisoners keep their right to vote from court all the way to their release. The rest of the states vary in their laws: some operate with automatic restoration post-release; others require those fines and fees to earn back the right, and, in some, your fate depends on the crime committed.

The laws have no shared basis. For there to be so much state-by-state variation on federal charges is nonsensical. A nationwide precedent must be set.

Some argue that disenfranchisement is part of a felon’s punishment. If you do the crime, you pay the time. Though, such arguments fail to consider that prison itself is the punishment. The isolation from society, from your family, from your community, is punishment enough. Taking it further and removing civil rights goes too far.

Or, on the other side of the spectrum, people may argue that disenfranchisement is the last thing to worry about — first comes the broken system as a whole. And while the justice system does need an overhaul, there is no better method than to give those affected their voice back. Felons must be at the forefront of justice system reform — they know it better than anyone. In order to tear down walls and reconstruct the system, we must first give back the power to those trapped within.

Bottom line: felons deserve to vote. Where they are in their sentence doesn’t matter; whether a felon is currently in prison, is on parole, or has been released, disenfranchisement is unjust. It treats prisoners as less than citizens and upholds our nation’s continued history of racism.

We must become the model democracy we so often claim to be. Whether someone robbed a bank or dealt cannabis, they deserve the same token of citizenship we all do. Give back voting rights — prisoners are people, too.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop Editorial Board and was written by Sophie Gurdus. The Editorial Board voted 9 in agreement and 3 refrained from voting.