In 2021, admitted Harvard student Abigail Mack’s personal statement went viral, accumulating over 28 million views on TikTok.

In the essay, Mack writes about her resentment of the letter “S” because it represents the loss of her mother, leaving her with only one “parent” instead of two.

Many users were in awe of her essay, filling up the comment section with compliments and requests for writing advice.

However, some viewers had a different takeaway, leaving comments like “I don’t have a sad story, so I guess my college essay will be bland” and “So if I wrote about an essay when my dad died, I’d be at Harvard — great.”

Undoubtedly, Mack’s acceptance was not simply a result of her personal statement. As she explained in response to a comment, her hard work and abundance of extracurriculars also made her a competitive candidate for the university.

However, as shown by the “less positive” reactions to her essay, the viral statement contributes to the belief that students must not only have endured trauma but also put it on display for admissions officers to be competitive college applicants.

American college essay prompts often ask students to interrogate who they are, who they want to be, and what the most impactful experiences of their then-short lives are. They ask students to share a story, to break down their identity to the inquisitive gaze of admissions officers — all in a succinct 650 words.

The American admissions process rightly grants students broad latitude to write about whatever they choose, with prompts that emphasize personal experience, adversity, discovery, and identity.

The essay portion of college applications isn’t inherently problematic; in fact, it offers an opportunity for exploration and self-reflection, serving as a powerful vehicle for students to convey a part of their identity by writing profoundly and candidly about their experiences.

But as the acceptance rates of top colleges continue to drop and students grow more determined to stand out among a growing number of applicants, the system that demands such introspection makes students feel required to write about their adversity to differentiate themselves, diminishing the personal essay’s capacity to bring on meaningful self-reflection.

A desperate effort to stand out

According to Common App, application volume rose 7%, with the 6,818,541 applicants in the 2022-2023 application cycle reaching 7,327,247 in the 2023-2024 cycle.

Beyond the rising applications, many academic institutions are also experiencing record-low acceptance rates. For instance, Yale University announced its lowest-ever acceptance rate of 3.7% in April, down from 4.5% last year, according to Inside Higher Ed. Other highly selective non-Ivy institutions such as Williams College, Rice University, and Duke University also boasted record-low acceptance rates.

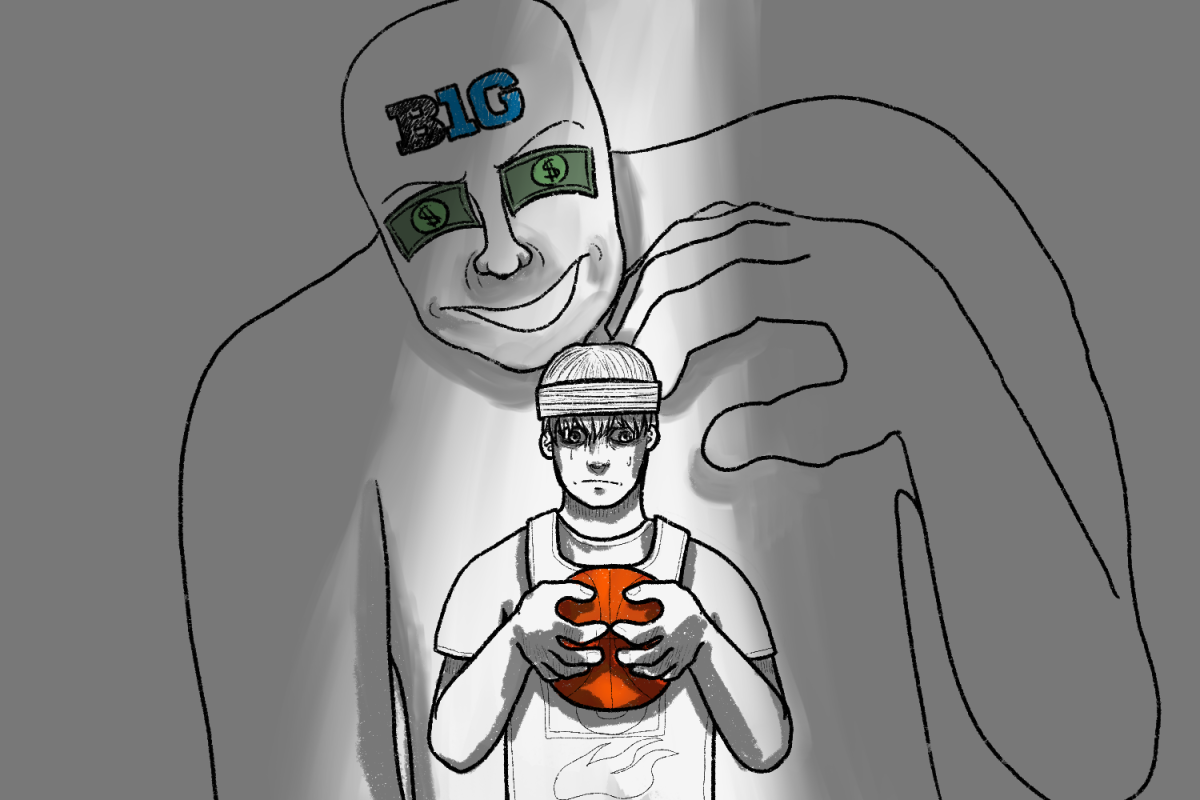

As it gets harder and harder to stand out, students begin to feel obligated to supply the sort of dramatic, attention-grabbing content that just might get them an acceptance letter in return, resorting to a problematic approach: using trauma for drama.

Joyful, restful days don’t make for riveting stories; few plot points exist in a stable, happy relationship with a living, healthy relative. Trauma — on the other hand — often becomes the kind of compelling narrative that feels worthy of a top college acceptance.

The concept of students centering their college essays on their personal trauma has been dubbed “trauma dumping.” Viral social media stories, including Mack’s, have popularized this essay-writing approach, where trauma essays are portrayed as the “make-or-break” factor in college applications.

Whether it’s an experience of homophobia, racism, parental alcoholism, a chronic disease, familial loss, or some other form of deep emotional pain, people who have traumatic experiences feel pressured to write about those things because they are personal, interesting, and unique — just the qualities of an essay colleges are looking for.

Commodifying adversity

The problem with trauma-focused essays isn’t just the choice of the content itself but also that students feel pressured to present the traumatic material in a way that markets themselves, which often leads to exaggerated or fabricated narratives.

For students who have experienced genuine adversity, this pressure to package hardship into a palatable narrative can be harmful. The essay risks commodifying adversity, rendering profound, life-shaping experiences into shiny narrative novelties that melt down into an acceptance letter.

This commodification of hardship can leave applicants — admitted or not — feeling their worth is tied to their most vulnerable moments.

Additionally, students often feel compelled to conclude their essays about heavy topics on a victorious note — to proclaim that they have overcome their problems and are now ready for admission.

But the truth is that very few 18-year-olds have figured life out. Trauma often sticks with people well beyond college, and the expectation to present a clear resolution can make students feel as though they’ve “failed” if their pain resurfaces later. Not all wounds heal entirely — but no one wants to read a sob story without a redemption arc.

The personal essay often becomes a tug-of-war between honesty and embellished appeal for students without such trauma. The pressure to craft a narrative as riveting as others’ can push students to exaggerate or fabricate their experiences to appear as those of heroic problem-solvers.

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn race-based affirmative action puts an even harsher burden on applicants’ essays. Colleges can no longer consider the systems of inequity that may impact students of color, but applicants can write about their experiences as marginalized individuals in their essays.

However, this dynamic is both unjust and deeply flawed, for students from marginalized backgrounds should not feel obligated to offer neatly packaged stories of resilience to prove their worth. They should not bear the disproportionate burden of justifying their place in higher education with narratives of hardship.

Individuals and institutions must reject this exploitative premise altogether and, instead, work towards fostering an environment that encourages authentic self-expression without coercion.

Rewriting the application process

Both students, colleges, and other parties involved in the college application process must strive for an admissions system that balances openness with reduced pressure, creating space for genuine self-expression.

Other models, such as the United Kingdom’s UCAS personal statement, prioritize intellectual curiosity alongside personal experience. Similarly, the Rhodes Scholarship recently revamped its prompts to shift away from an overemphasis on the “heroic self,” encouraging applicants to reflect on themes like “self, others, and the world.” Observing how these alternative frameworks shape essays over time could provide valuable insights into whether such approaches are worth emulating.

Meanwhile, students should remember that neither their struggles nor their college essays define their worth, as there are countless ways to stand out to admissions officers, including by speaking about their passions, the parts of life they find joy in, and other meaningful aspects of their identity.

For those who choose to write about challenging experiences, it’s essential to lean on the conflicts of their life only in authentic ways. No one is defined by their trauma; instead, they are shaped by it.

Those who feel their most reflective stories are rooted in tragedy should reconsider how they write about their trauma, for admissions officers won’t just focus on the traumatic event itself, but also why the applicant chose to include it, what they learned from the experience, and how they will carry that event’s impact into the future.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Editorial Board and was written by Naomi Hsu. The Editorial Board voted 8 in agreement, 5 somewhat in agreement, and 2 refrained from voting.