Content warning: this editorial discusses topics that may be triggering to certain readers.

Messages with warnings about subject matter within posts, movies, shows, and more have been popping up on the internet since the early 2000s. The term “trigger warning” was derived after psychologists named the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms of veterans who had fought in World War II “triggers.”

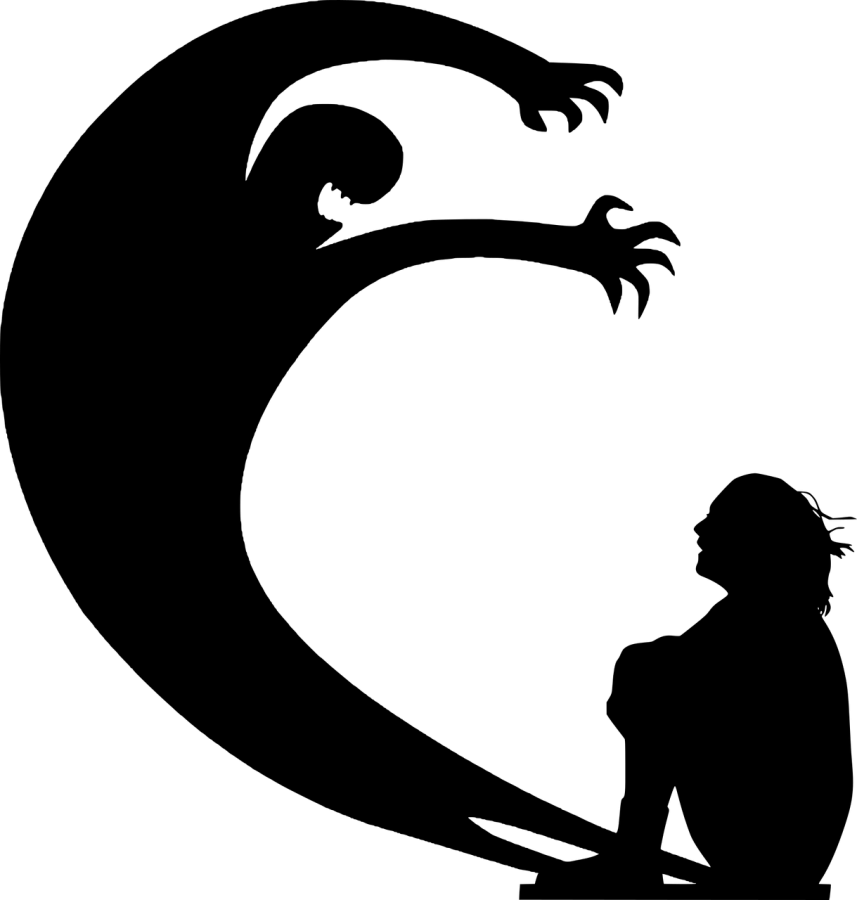

It’s important to recognize that each trigger is as valid as the next and act accordingly. Just as gunshots can provoke a soldier’s PTSD, readings at school can cause flashbacks that are psychologically harmful to students. Triggers can be relevant to eating disorders, suicidal thoughts, and various other disorders. People are now using content warnings to preface content to distinguish between the physical instigants of PTSD and instigants of disorders with more visual triggers.

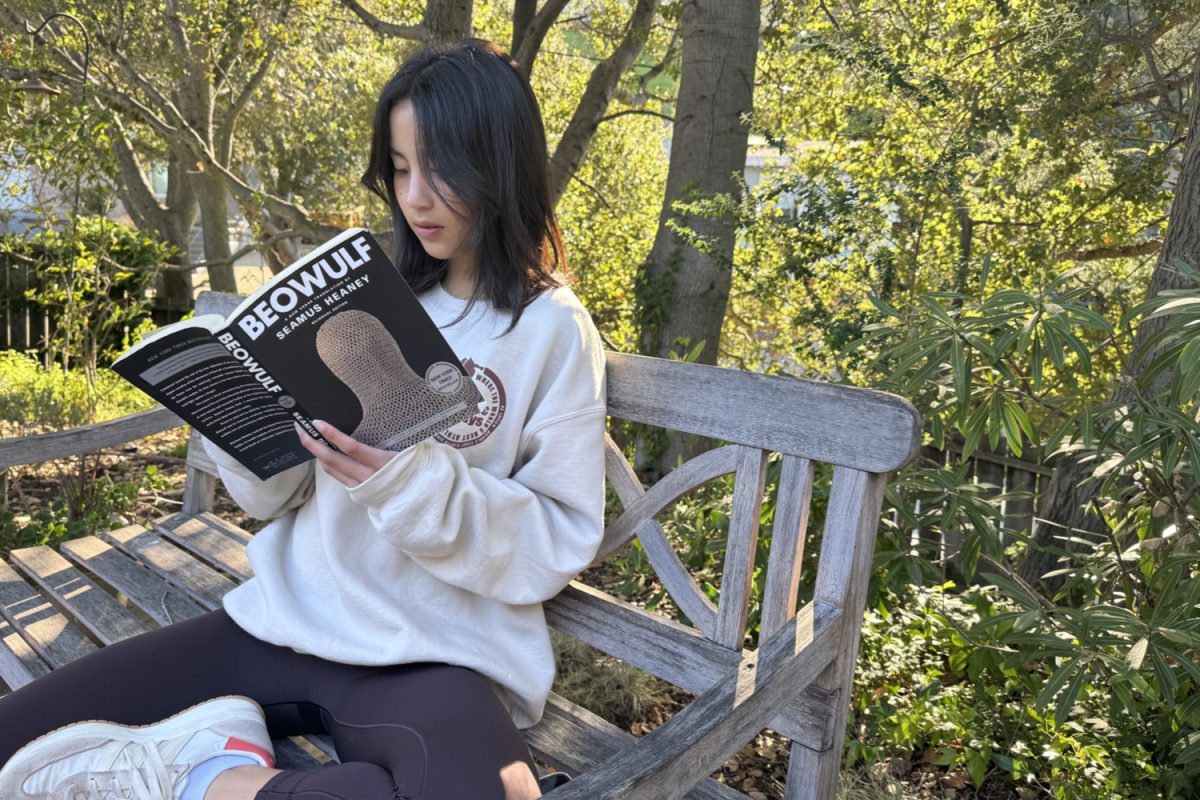

Carlmont’s curriculum has included many books that included potential triggers, including rape, violence, and self-harm. But none of these books have included content warnings. This is despite the fact that 31.9% of adolescents are diagnosed with anxiety disorders.

This is unacceptable. Some of the visuals and written words in our textbooks and English novels can cause severe relapses in many mental disorders. If schools decide to push out such content to students that could be potentially traumatic, trigger warnings should be put on this material.

Some may argue that students could potentially use these warnings as an excuse to leave class and avoid learning important material. But more often than not, this is not the case. According to NPR, the most that happens when professors include warnings is that some students step outside for a few minutes.

There is the question of what content requires warnings and what does not. Many teachers find themselves in the predicament of not wanting students to easily exit topics that may challenge their beliefs, such as texts on racism. Others may worry that content warnings could be warranted for an infinite amount of subject matter, taking away time from their lessons.

However, content warnings are not designed for these topics but rather specific phrases that may relate to a person’s trauma. For instance, general examples of racism are not traumatizing, whereas specific acts of violence might be. This means that students do not usually need to skip whole discussions or texts but rather avoid specific phrases and parts of texts, meaning content warnings cause a two-sentence inconvenience for teachers, not the creation of a new curriculum.

Others argue that teachers shouldn’t change their habits for a select few, but this has not been the case for other problems plaguing schools, and rightly so. About 0.6% of people are transgender, and Carlmont has gender-neutral bathrooms. Only about 2.3% of students have 504 plans, and Carlmont instituted the system schoolwide. Why should it be any different for the 5% of students with PTSD, not to mention countless other disorders with triggers?

Ultimately, Carlmont’s inability to address the needs of students who have greater mental health problems needs to be fixed. A simple warning could save a student from an abundance of trauma.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop editorial board and was written by Lindsay Augustine.