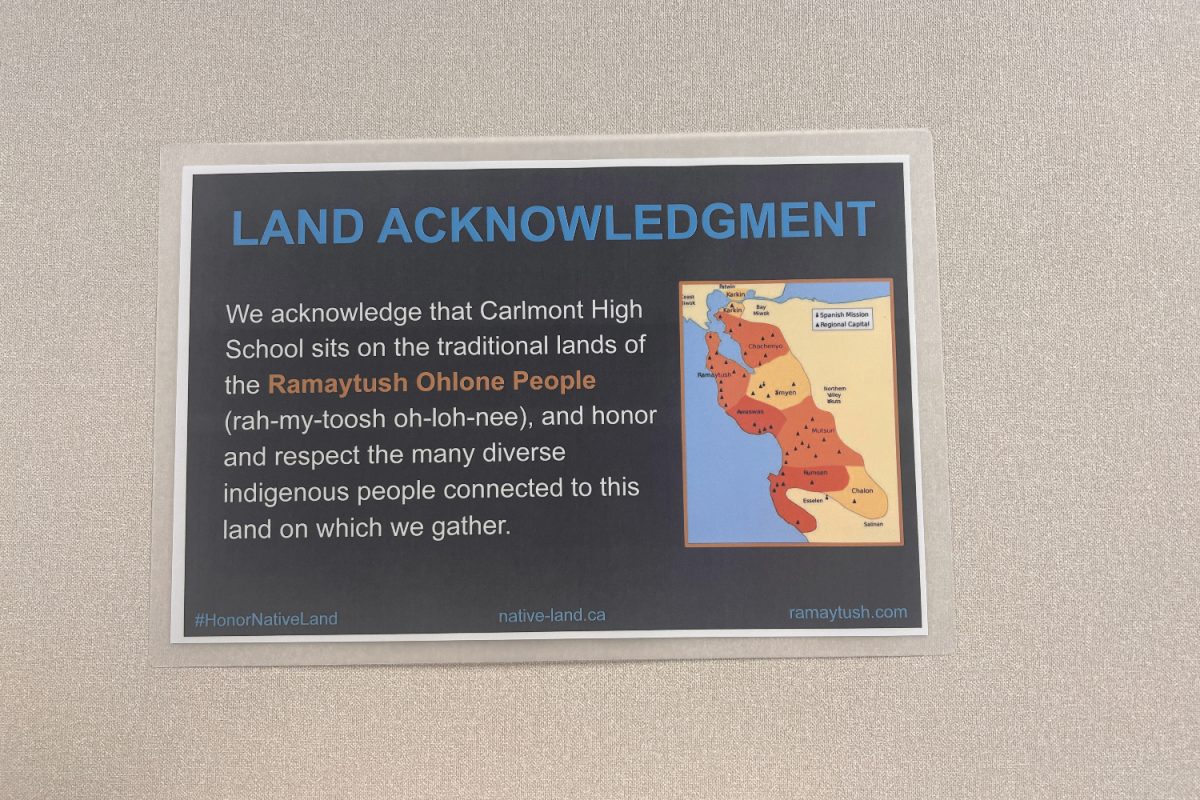

“Land Acknowledgement: We acknowledge that Carlmont High School sits on the traditional lands of the Ramaytush Ohlone People… and honor and respect the many diverse indigenous people connected to this land on which we gather.”

Just one example among many other variations, land acknowledgements are formal statements that recognize Indigenous Peoples as traditional stewards of land as well as acknowledge the enduring relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional territories, according to Northwestern University Native American and Indigenous Initiatives.

Beginning in Canada in the 1970s, the practice of land acknowledgements has since expanded to countries like the United States and Australia as a means to honor and acknowledge their respective Indigenous Peoples–referred to in Australia as First Nation Peoples–often being read before events and displayed on signage in schools, venues, and other places.

The United States’ tribal history shouldn’t be overlooked, and nor should colonialism’s effects on it. Having first arrived in the present-day U.S. about 30,000 years ago, Native Americans, with a population estimated to be between 9.8 and 12.2 million, occupied an estimated 54.92 square kilometers in the United States. Following Christopher Columbus’ arrival in 1492, Native Americans have since lost roughly 99% of their lands and 95% of their initial population, illustrating the devastation and everlasting impacts of colonialism on Indigenous history.

However, in the 247 years since our nation was founded, we have done little to make up for the devastation, and, worse, mostly furthered the devastation with events like President Andrew Jackson’s infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830 that forcibly removed many Native tribes to lands west of current-day Mississippi.

While acknowledgement forces those who hear them to stop and think for a moment, taking long-lasting and impactful actions is far more important. Land acknowledgements often fall short of what they aim to accomplish and come off as performative.

Instead, we should aim our attention towards alternatives to support Indigenous Peoples, like donating to Native charities to support their present-day survival and preservation of their culture, as well as supporting Native-led causes, in regard to current-day issues like the environment and education.

In an interview with NPR, Kevin Gover, the Under Secretary for Museums and Culture at the Smithsonian and a citizen of the Oklahoma Pawnee Nation, voiced his dislike for land acknowledgements.

“If I hear a land acknowledgment, part of what I’m hearing is, ‘There used to be Indians here. But now they’re gone. Isn’t that a shame?’ And I don’t wish to be made to feel that way,” Gover said.

Rather than only publishing an acknowledgement, institutions should focus more so on taking concrete, tangible actions that truly have an effect on the Native peoples we are attempting to impact. While acknowledgement certainly forces those who hear them to stop and think for a moment, actions always speak louder than words, and we must follow through on our attempts to reconcile and take responsibility for our nation’s history with Native American tribes.

*This editorial reflects the views of the Scot Scoop Editorial Staff and was written by Emma Goldman. The Editorial Staff staff voted 15 in agreement and 1 refrained from voting.