Memes.

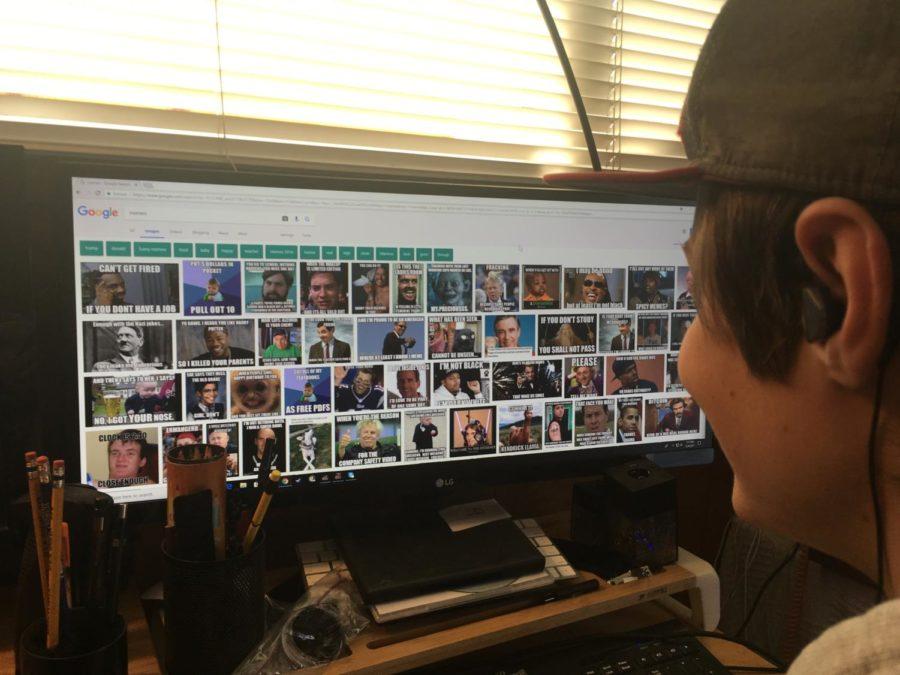

We all know them: the funny pictures with the big white text or everyone’s favorite frog sipping tea after making a snarky remark.

However, memes are more than just funny pictures with words.

The term “meme” was first used by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his book “The Selfish Gene,” published in 1976. It’s a shortened version of the Greek word “mimeme,” which translates to “imitated thing.”

He described a meme as a self-replicating cultural entity that could be used to study human behavior. Basically, the cultural equivalent of a gene. However, many people defined memes as many different things, so no one could really study memes or how they affected human culture.

The term “meme” was not popularly used again until the creation of the internet. With the internet, people could share ideas and pictures in a matter of seconds, and they would reach a much wider audience. Thus, the internet meme was born.

According to World History Project, one of the first internet memes was the dancing baby or the “oogachaka” baby.

In 1996, the company Viewpoint Datalabs released a model bank of experimental files and data. Among these was an animated video of a baby doing a dance similar to the chacha.

This video almost instantly went viral and the song “Hooked on a Feeling” by Blue Swede was often played in the background. People started to make spinoff videos like the samurai baby, and it even made several appearances on the widely popular 1990’s television show “Ally McBeal.”

Since then, internet meme production has skyrocketed, and, according to The Odyssey, memes have become an essential part of human culture.

People use memes in a variety of ways, such as making a joke, attempting to gain popularity, a form of marketing, or a way to express ideas.

“Memes are an art medium for coping with the world,” said sophomore Max Hariri-Turner.

During the 2016 presidential election, meme popularity had increased heavily and it had reached a new all-time high. Memes about the election and its candidates were being churned out constantly and according to a study by Priceonomics, the slogan “Make America Great Again” had shown an increase of 1.2 million percent in memes from January of 2016 to January of 2017.

Studies done by Pew Research and Common Sense Media show that 91 percent of teens ages 13 to 17 say that they use the internet daily and that around nine hours each day is spent on some form of media. With all of this media consumption, teens are bound to come across a meme or two, and according to Hariri-Turner, it doesn’t usually take long.

“Anytime you’re doing work and you see a meme, you can get sidetracked,” Hariri-Turner said.

With the use of social media, news gets around pretty quickly, leaving little reason for teenagers to tune into their local news station.

This news can also be presented in a variety of ways, including in memes.

Some memes try to take current events and portray them in a humorous or joking way.

For example, many memes were produced relating to the hurricanes in Texas and southeast America. These memes included ones where hurricanes were turned into fidget spinners and where “Family Feud” host Steve Harvey’s head was photoshopped onto Hurricane Harvey. Other memes relating to the hurricanes were comprised of humorously captioned photos.

According to Pep Rosenfeld, a comedian and speaker at TEDxAmsterdam, comedy actually does make information easier to retain. Laughter releases chemicals called endorphins that make people happier, more relaxed, and more receptive. This means it’s easier for someone to retain information that amuses them like a meme would.

However, the goal of most memes is not to make events memorable but rather to solely portray them in a humorous manner.

This may skew teens’ perception of the events that are taking place around them, as they are mostly seeing these events in a humorous light. When people only get information from one source or the majority of their attention is focused on one source, their understanding of information is confined to the way the information was presented.

And this is where problems may arise.

According to Vanity Fair, the memes used by Russian Facebook accounts during the 2016 presidential election did have an effect on the outcome. People constantly saw these memes on Facebook and, after repeated exposure, it started to sway their beliefs.

Memes aren’t that harmful on their own, but when coupled with an uninformed mind, they can cause misconceptions and allow for superficial understandings.

“We [are all guilty] of spreading ignorance when we share, or like, or link, or even give credit to lies and misinformation,” said Trever Bierschbach, a writer for the online magazine Frags and Beers. “Some of these memes are even like political cartoons in that they are meant to be funny. Unlike political cartoons, almost anyone can create them, which means one can never be sure of the real intent of the meme.”

Memes come in all shapes and sizes and can have any intended meaning. However, it is up to the consumer to interpret the meme and to determine if the information it is conveying is true or false.

“People process [a meme] and then do one of a few things,” Bierschbach said. “Some look at it and know right away it’s bunk and they dismiss [it]. Others hit the share button as fast as their cursor will move. A small group will actually look it up to see if it’s true or not.”

Fact-checking information seen in memes and social media is key to identifying whether it is real or fake, yet most people do not take this extra step. A study by Zignal Labs shows that 86 percent of Americans do not always fact-check the information they read on social media.

“We need to take the few seconds to Google that headline, or that meme,” Bierschbach said. “Look up that issue and see if that humorous little quip is just innocent satire or a malicious lie.”

Memes have become an integral part of our culture and a cornerstone for expressing beliefs and interests. However, they have also gained the power to take information and show it in a misleading way, spreading false information.

“Memes have equal power to rip things apart or put them back together,” said Hariri-Turner.