Weed.

Pot.

Marijuana.

These names refer to the simultaneously legal and illegal Schedule I controlled substance known as cannabis. The status of cannabis as a Schedule I controlled substance means that it is one of the most restricted substances on the Drug and Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) radar. According to the DEA, marijuana has a high potential for abuse and is not currently accepted federally for any medical use; this may come as a shock due to marijuana’s medicinal and recreational legality in states like Colorado, California, Oregon, Washington, and many more.

On the federal level, marijuana is currently illegal. However, some states can allow marijuana to be consumed and sold on their territory due to state power. This situation causes marijuana to be in a “grey area” regarding arrests.

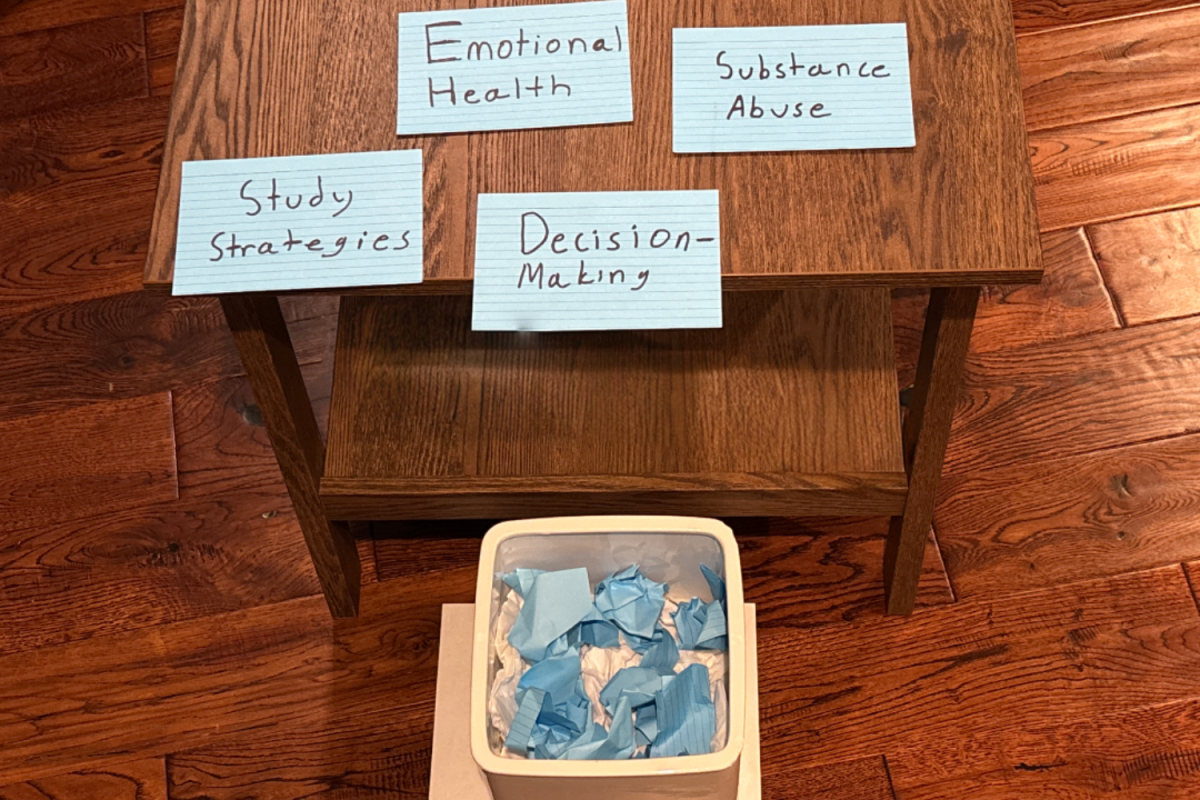

In the Netflix documentary “The Business of Drugs,” former CIA agent Amaryllis Fox explores the complex world of cannabis legislation. The documentary mentions that despite cannabis being legal in California, only about 20% of business is within the legal market. The documentary explores the legal hoops potential vendors must jump through, one of the largest ones being capital. For example, the simple process of applying for a marijuana retail sales license in California costs around $3500 annually. After this, one can expect to pay from $4000-$72,000 a year for the license, depending on the size and scale of the business. Legislation like this is blatantly classist and makes it extremely difficult for smaller-scale marijuana businesses to stay above ground, in both profits and legality.

In the documentary, Fox visits a family-owned medicinal marijuana farm that is struggling to stay afloat due to massive fees and several industrialized centers that grow marijuana in downtown Los Angeles. The stark contrast between the two business types displays how hard it is for people without a huge capital base to legally survive in the marijuana business. If the family farm sold marijuana illegally, the massive amounts of fees they had to pay as a legal business would be virtually gone, but in their place would be a greater risk of prosecution by authorities.

Notice how the risk of prosecution is still present, even when selling marijuana legally. Although the bureaucratic process of selling cannabis is a pain for vendors, the real trouble comes with cannabis being illegal under the federal government but legal in California. People can still face criminal charges for selling marijuana entirely under the jurisdiction of California laws. Marijuana being a Schedule I Controlled substance doesn’t help vendor’s cases either; the Federally Controlled Substances Act makes the sale or attempted sale of marijuana in quantities under 50 kilograms punishable by a felony charge, five years in prison, and up to a $250,000 fine.

The government can also deal punishment to those who are simply growing marijuana. For the cultivation of just 50 plants, farmers can expect to deal with the same fines and charges as they would get for the selling of 50 kilograms. A 2019 cannabis-equity analysis of Humboldt County, California, found around 742 drug-related arrests happen per year. Despite Humboldt being the first county to pass laws concerning cannabis that align with state legislation, it still is a center of cannabis-related arrests. Since the 1970s, one of Humboldt County’s primary sources of commerce has been marijuana, 40 years before legalization even happened.

Humboldt County is one point of the so-called Emerald Triangle of California, along with Trinity and Mendocino County. This long period of illegal operations has made it a difficult transition for farmers to start selling legally. Marijuana’s new state legality also is raising questions about what should happen to those arrested for cannabis-related offenses before legalization. Due to the risk of prosecution still being present for legal businesses and the associated fees with legal selling, many businesses choose to stay below ground.

A benefit of more explicit legislation would be increasing job opportunities for non-owners of the businesses themselves. One example of a place where the number of job opportunities came into focus is in Adelanto, California, a desert town in San Bernadino County. The city is now infamous for being a center of cannabis cultivation and even has a college scholarship funded entirely by cannabis profits. The combined illegal cannabis industry is worth billions of dollars, a virtual gold mine for all parties involved. Imagine how many job opportunities would come with standardized, clear laws concerning marijuana sales in California alone. The federal and state governments incentivizing legal vending of marijuana is direly needed and would better all facets of the industry.