Hydrogen was once touted as the replacement for oil.

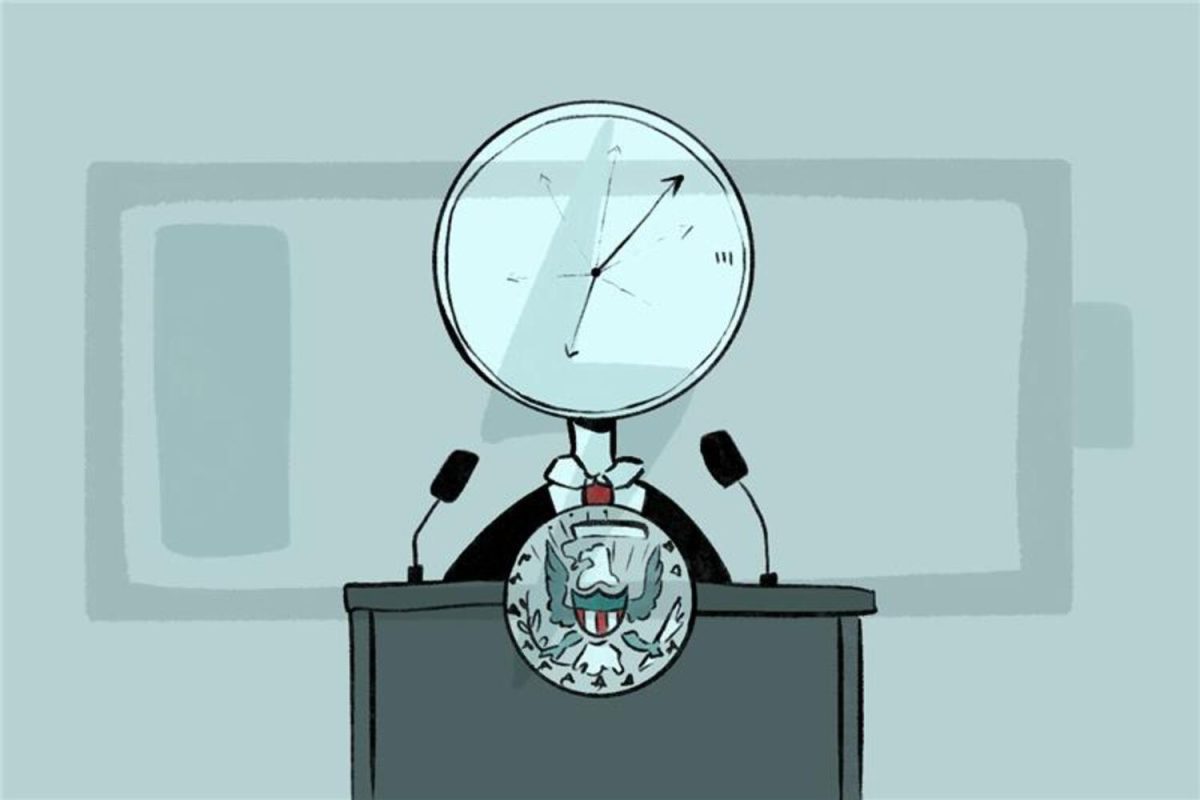

George W. Bush announced a $1.2 billion fuel initiative to advance hydrogen technology and infrastructure in 2003. Former California Governor Jerry Brown approved Assembly Bill Number 8 in 2013, which funded the infrastructure to put 1 million zero-emission cars on California’s roads by 2030. This was a plan to revolutionize car culture and envisioned hydrogen vehicles as the future.

Now, hydrogen cars have lost all traction, long forgotten and outshone by a wave of electric vehicles (EV), and most carmakers have disregarded hydrogen in favor of electricity. However, it is still vital for the future of zero-emission cars and will play an essential part in California’s automotive future.

Last December, Toyota released the second-generation hydrogen car Mirai; its predecessor was the first of its kind to hit the consumer market in 2015. There are currently two other hydrogen cars available: the Hyundai Nexo and the Honda Clarity.

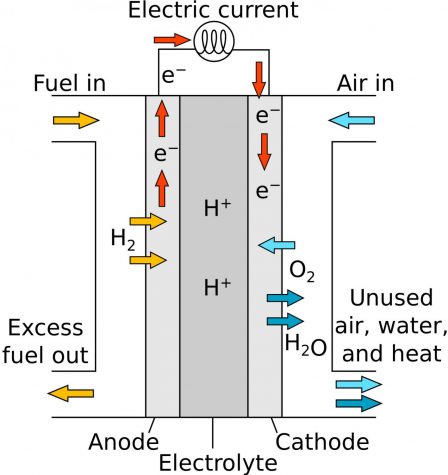

These cars can be topped up in a matter of minutes like ordinary vehicles, but run on electric motors like a Tesla, so are classified as a hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV). According to the U.S. Department of Energy, cars take in compressed hydrogen, which is run through the fuel cell. Then, the hydrogen is separated from its electron to form a positively charged ion and is passed through an electrolyte to the other side. The electron, in turn, powers the motor and combines with the hydrogen and oxygen from intaken air to form water. Simply put, hydrogen is converted into energy that powers the motor, and the only byproduct is water.

The most significant selling points for FCEVs over EVs are the convenience of no charge time and the range. The 2020 Toyota Mirai has a range of 420 miles, and in comparison, the Tesla Model Y has a range of 326 miles. These strengths are meaningless when only 48 hydrogen fuel stations exist in the U.S. Furthermore, according to California Fuel Cell Partnership (CAFCP), it costs $2 million to build a hydrogen station, as opposed to $40,000 to install a fast-charging station.

That being said, 47 of those stations are in California, split between Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Through Assembly Bill Number 8, the state has partnered with CAFCP to build 200 hydrogen stations by 2025 and 1,000 by 2030. The state has also provided monetary incentives to FCEV buyers. According to Auto Blog, the $50,000 Mirai was $17,995 after Toyota’s $20,000 incentive and California’s tax rebate, which is still active, from December until March.

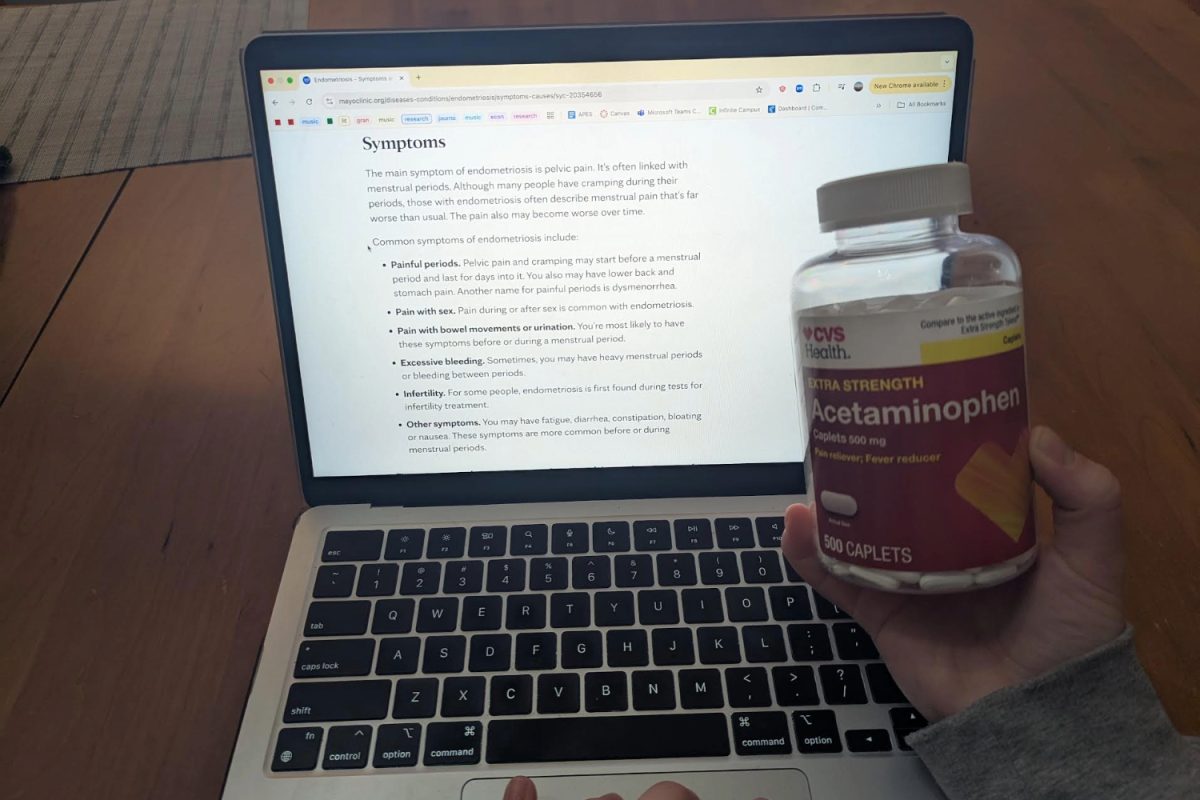

In recent times, another considerable criticism arose. Are hydrogen cars even that environmentally friendly? In Volkswagen’s statement to choose electric over hydrogen, the company pointed at FCEV’s poor energy efficiency as a factor.

Hydrogen is highly volatile and cannot be found in nature by itself. Thus, in electrolysis, where electric current is passed through water, it gets hydrogen by itself, which is then compressed, transported, and finally passed through the fuel cell. A study done by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that this process was approximately 57% energy efficient. This means if 100 watts from a power turbine were used, only 57 watts would be effectively converted to power the car, a far cry from the 77% energy-efficient electric vehicle, but still much better than the 12% to 30% energy-efficient gasoline vehicles.

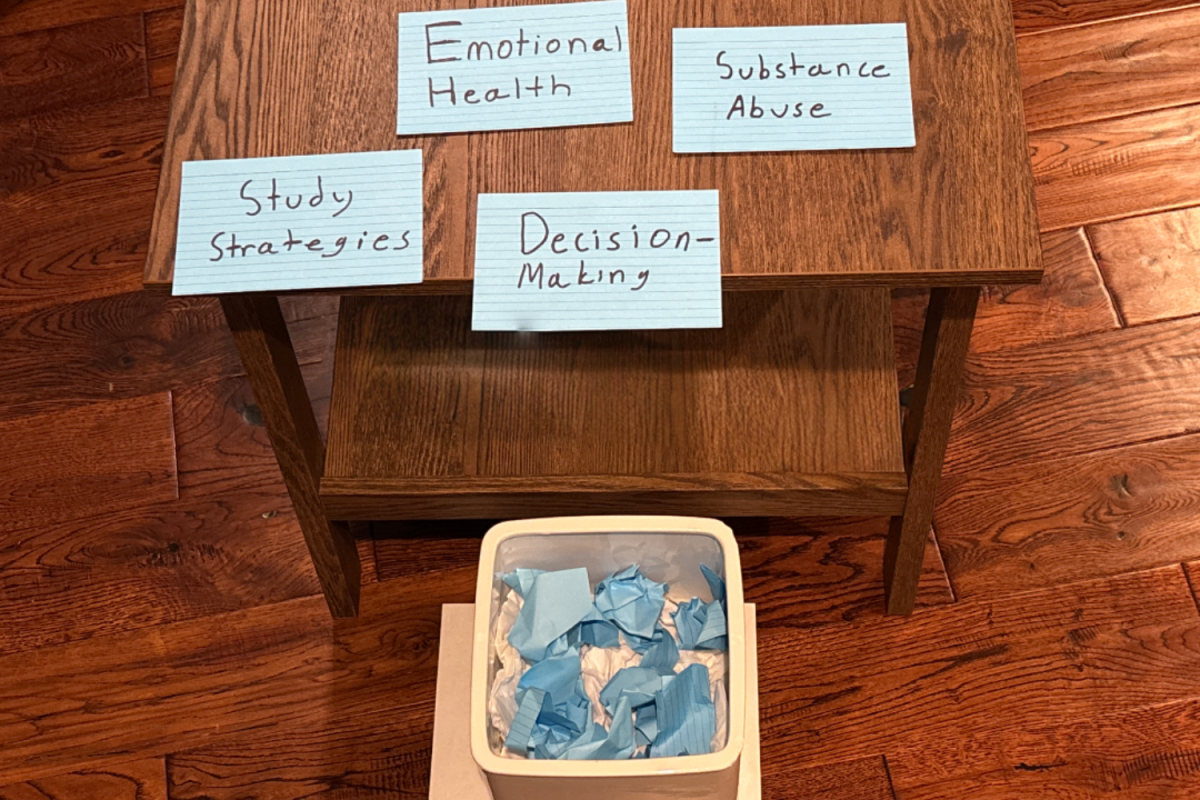

It is unfair to look at Hydrogen cars from a single statistic, though. Many, including Volkswagen, look past the environmental cost of producing the vehicles in the first place. According to Deloitte, a fuel cell requires platinum and ruthenium. The lithium-ion battery of an electric car requires lithium and cobalt. The mining for platinum, ruthenium, and cobalt are all detrimental to the environment. Moreover, cobalt mines also have huge humanitarian controversies on child labor.

The largest lithium deposits are found in the “Lithium Triangle” between Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile, where 75% of the world’s supply resides. According to Harvard International Review, 65% of the region’s water supply is consumed by mining creating disastrous water shortages for local farmers. Overall the carbon footprint of an FCEV turns out to be 2.7 grams per kilometer, and it is much smaller than an electric car, 20.9 grams per kilometer, according to the Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association.

The hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle provides an alternative in the zero-emission automobile market. The charging time of EVs are a let-off for many customers; FCEVs present a solution. California is one of the few places globally with commendable hydrogen fuel infrastructure, and it will only get better in the next couple of years. FCEVs will race alongside EVs in California’s journey to net-zero emissions and a healthier environment.