In 2016, an empty seat in the Supreme Court brought about a partisan contest: who could hold out the longest and act the stingiest to secure the spot?

The argument made a broader issue clear. The stakes for the empty seat were driven up the wall, so much so that the Senate saw attempts to reject the other party’s judicial nominee, questionably motivated speeches, and something nationally recognized as nuclear to circumvent long-standing Senate rules.

Stakes for a seat rise because of infrequent judicial vacancies in the first place, bringing attention to a need for change in the system: we need to regulate the turnover of justices.

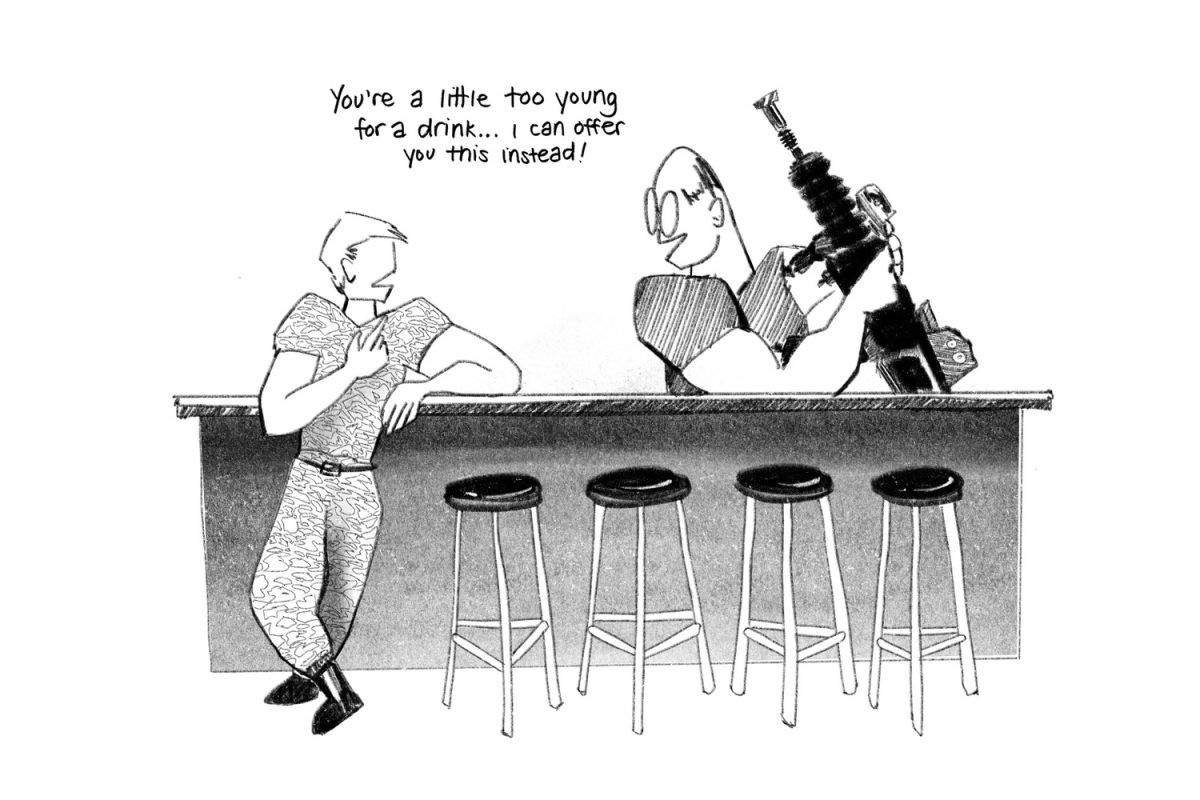

As it currently stands as outlined by the Constitution, Supreme Court justices lack term limits, so the number of justices each president gets to appoint is largely out of their control. For example, former President Richard Nixon appointed four during his term from 1969-1974, while while his successor, former President Jimmy Carter, appointed zero from 1977-1981.

This irregularity emphasizes a discrepancy and politicizes the confirmation process. Nominating a justice likely to serve for over two decades makes a difference, even in the theoretically nonpartisan Supreme Court. In 1969, Chief Justice Earl Warren informed then-President Lyndon B. Johnson of his retirement a full year before he left the court, concerned that a Republican Party candidate would win the dawning presidential election and appoint his successor, according to the Senate.

The stakes for one party to secure a vacant seat would be lowered by regularly vacant seats, as there would be an understanding that the appointee would serve for a predetermined amount of time. Term limits reduce the political incentives of nominating a Justice as it would be accepted each president would appoint and replace a certain number of justices.

It may be argued that a regular turnover of justices would subject them, and the Supreme Court at large, to the whims of the current political majority and cause upheavals in law. However, a fifteen to twenty-year term would be long enough to avoid partisan whims but still short enough for regular turnover. A judge would be replaced every two years, allowing the Court to reflect the societal landscape.

The assumption that regular term limits would upheave law is misplaced. In principle, the Supreme Court emphasizes stare decisis or the upholding of precedent, meaning previous decisions create a stable and consistent foundation for the Court’s rulings.

In Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt, Chief Justice Roberts voted in favor of a Texas law against abortion. However, the law was struck down, and when an almost identical Louisiana law came before the Court in June, Medical v. Russo, Roberts voted against the law based on upholding the previous decision, according to Stanford Law.

But even while assuming the Court will stray from precedent, as it did in overturning Roe v. Wade, the amount that the Court would stray depends on how closely the judges are ideologically aligned with their nominating president and how much they defer to precedent, not how long they are in office.

The Court will still upheave law if they are partisan or don’t defer to precedent with a lifetime term, as illustrated by Roe v. Wade. There is nothing about a term limit that increases partisanship or reduces deference to precedent. Irregular vacancies incentivize one party to nominate an ideologically aligned, young candidate to promote their view in the Court for as long as possible.

The Constitution that drafted lifetime terms was written almost 250 years ago when people died at 40. Society adapts, as should the Supreme Court.