The teacher and substitute shortage has become a national challenge for schools as districts scramble to fill vacant positions while the number of teaching candidates declines.

Across the country, school officials are attempting to hire and attract new teachers, while simultaneously working to retain the staff that they currently have. This year, 44% of public schools reported having at least one teaching vacancy, with over half of these vacancies being due to resignation, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

In the Bay Area, major factors such as low wages paired with the high cost of living and housing prices have contributed to fewer teachers and substitutes available.

Beverly Gerard, president of the San Mateo County Board of Education, says that rising housing costs have been a significant obstacle for districts in attracting and retaining teachers for years.

“Teacher salaries, even at the higher levels for long-tenured teachers, make payment of market-rate housing costs nearly impossible, without a second household income, and many salaries are just high enough to be out-of-range for qualification for low-income housing,” Gerard said.

This often causes teachers to live in areas farther away from their schools, making daily commutes much longer.

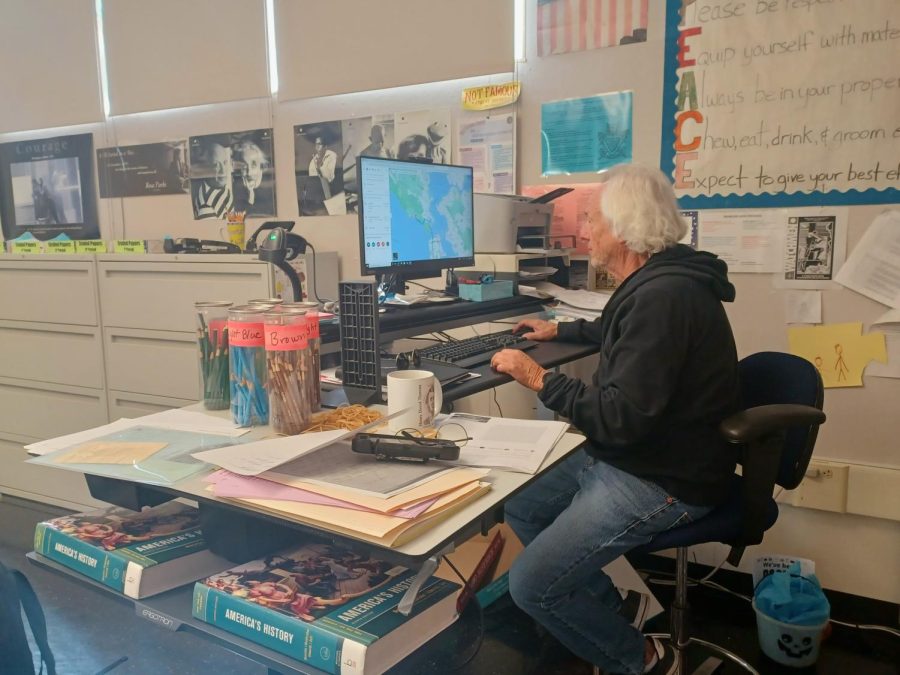

“I know teachers who live in places like Tracy, and they’ll drive an hour and a half just to work in this district because the cost of living is lower out there,” said Jeffery Tanguay, a Carlmont teacher and former substitute.

Other factors, such as COVID-19, are still affecting classrooms. According to an NEA survey, 55% of educators said they would probably leave teaching earlier than planned due to the pandemic.

“Teaching has always been one of the most stressful professions, and when during the pandemic teachers were asked to do so much more, while at the same time being under increased demands and scrutiny, their wellbeing and health were impacted,” Gerard said.

Though, according to Gerard, San Mateo County districts “were already experiencing year-over-year declines in teachers entering the profession and high rates of retirement” prior to the pandemic.

The Sequoia Union High School District (SUHSD), however, is one of the few districts throughout California that has not been heavily affected by the teacher shortage this school year.

“Our district has a very high salary for the profession and teachers here at Carlmont have done a great job at building a sense of community amongst each other,” said Principal Gay Buckland-Murray. “So the nationwide epic of teachers resigning hasn’t impacted us tremendously. That being said, Carlmont is growing. We do need more staff right now. And because there are teachers leaving the profession there aren’t as many applicants for the open positions that we have, as we have seen in prior years.”

In contrast, the shortage of substitutes at Carlmont has presented further problems in filling classrooms.

“The sub shortage is definitely more of an issue, but the sub pay has been raised to counteract that, and there are a lot of us teachers who volunteer to sub for classes,” Tanguay said.

Even then, substitute teachers are paid fairly low and are not official employees of the district, so they don’t qualify for health benefits, making the job less appealing to those interested in the field of education.

“We have a smaller pool of subs to pull from and, at the same time, there’s a greater need right now for subs than there has been in the past because the reality of COVID is still with us. We have teachers who are going out to care for sick family members, sick loved ones who have COVID, or they themselves contract COVID. Those absences take longer, so we need more subs. But we have fewer subs, so this creates stress on the system,” Buckland-Murray said.

In areas where the shortage is more severe, students are suffering. Without enough teachers and substitutes, students can lose valuable instructional time, and schools must often resort to hiring less qualified teachers. Some United States districts have had to shorten school hours, cut extracurricular activities, or increase class sizes, making it harder for instructors to give each student the attention they need.

Todd Beal, assistant superintendent of human resources at SUHSD, emphasized that even though the district was able to fill all vacancies prior to the start of this school year, the teacher shortage remains a concern.

“Teachers have the biggest impact on student success, so it is important that districts spend the time and resources to fill teacher vacancies,” Beal said. “It is imperative that we have teachers in the classroom, and we have to be proactive in our hiring process and recruitment strategies.”

As the need for educators and substitutes grows, states and school districts have been working to implement new solutions to lessen the impact of the shortage.

Gov. Gavin Newsom recently signed Assembly Bill 2295, which will soon reduce zoning requirements for California school districts to more easily build affordable housing on their property for teachers and staff. Among the few places with educator housing in the nation, San Mateo County’s Jefferson Union High School District in Daly City has already opened 122 apartments to provide the staff and their families with affordable living spaces near their schools.

Earlier this year, another California bill waived skill requirements for new substitute teachers to get a 30-day emergency teaching permit, making it easier to earn the credentials needed by temporarily eliminating the requirement of passing the California Basic Educational Skills Test (CBEST).

Some schools in states most heavily impacted by the shortage have had to resort to more drastic measures. A few rural districts in Texas shifted to a four-day week this year. In Florida, military veterans are allowed to teach without certification, and a recently signed bill in Arizona authorizes college students to enter the classroom as instructors.

As for Carlmont, administrators and teachers agree that the positive community of educators at the school has helped to retain educators and minimize the impact of the shortage.

“So once a teacher gets hired at Carlmont, they really tend to stay if at all possible,” Buckland-Murray said.

To further demonstrate this, Tanguay, a first-year teacher, expressed his hopes for the years to come.

“I think Carlmont has a bright future ahead of it. I’m looking forward to working here, hopefully for my entire career.”