This year, sophomores in AP European History will have the option of taking the AP exam in May, something that was not offered to previous Western Civilization students.

AP European History teacher Linda Garvey said, “AP European History was created with the idea of providing kids with an additional challenge.”

Social Studies Instructional Leader Jayson Waller said, “Our department decided to offer AP European History in part because both Woodside and Menlo-Atherton have offered it as the advanced class to their sophomores for a couple of years.”

Carlmont now offers students a choice between four-point college prep classes and five-point AP classes throughout their sophomore, junior, and senior years.

Waller explained that freshman World History classes at Carlmont are requiring students to analyze more documents and are introducing more writing components to better prepare students for the challenge of AP European History as sophomores.

Current AP European History students, being the “guinea pigs,” may not be as prepared as future students will be for the course.

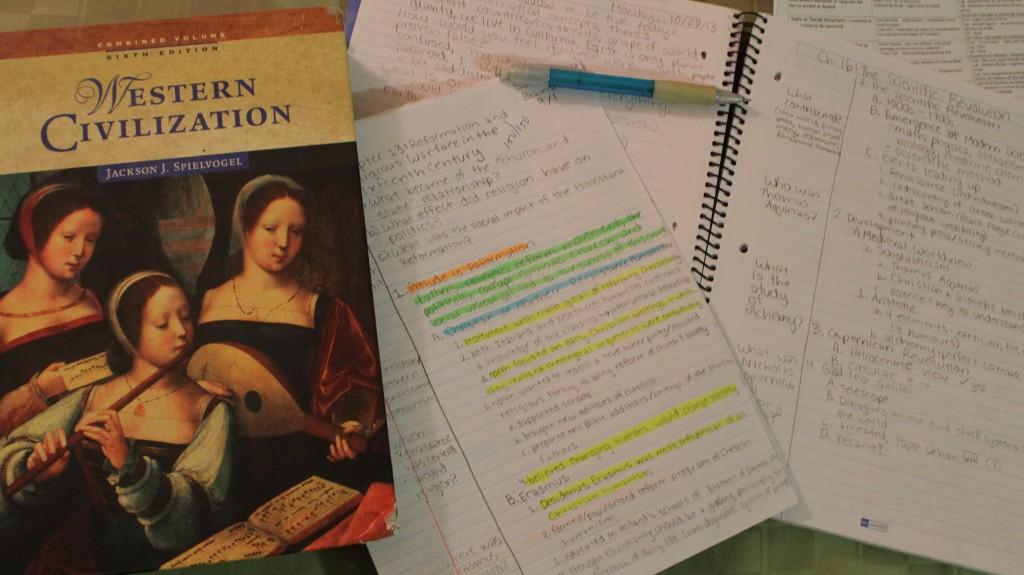

Waller explained that Carlmont’s Western Civilization course had already been using a college textbook for eight years. Students were already doing 70 percent of the reading for the AP course, and Waller proposed that with a bit more reading and exposure to writing skills, Carlmont could make Western Civilization an AP class.

The three Western Civilization teachers already preferred working on writing skills rather than group projects, making the course even more like an AP class.

Garvey said, “In Western Civilization, I rarely did group projects because I think there’s a real demand to teach good writing, reading, and pre-college skills.”

Patricia Braunstein, who has taught social studies at Carlmont for over 20 years, said, “AP European History is basically the same class with some tweaks.”

Because the course material is almost identical for Western Civilization and AP European History, people are questioning what changes qualify the European History students to take the AP test and gain college credit.

Waller said, “The biggest difference between the two classes is that there’s more reading and writing [in AP European History], but it has a purpose, a reward.”

A large part of the AP exam in May will be essays. To prepare, AP European History includes work with free response questions (FRQs) and document-based questions (DBQs).

Waller believed that his Western Civilization students’ writing would not have met the standard of the AP exam and pointed out that they had only covered 70 percent of the test material.

Braunstein said, “[The students] would have written and done alright. If they got a prep book and reviewed the stuff they could have taken the AP exam. Some of them still could; they just need to review.”

Braunstein’s class had always focused on developing writing skills, even before it was an AP requirement.

Garvey said, “We have different teaching styles. We basically agree on where we want to be at the end of the year.”

Although not all classes can be taught exactly the same way, all three AP European History teachers distribute grades based off of the same syllabus. All test and quiz questions, as well as essay prompts, are selected from the same pool.

Waller said, “We have a common pace that [may be] a bit off, but we all move towards the same final exam. [Different classes are] going to reflect the individual style of each teacher.”

The AP teachers are in agreement that AP European History is a more structured college prep class. The requirements and standards are very clear and concise.

Garvey said, “I didn’t really know what to expect, but seeing what I’m seeing, the kids who truly want to be in [the course] are generally very serious.”

Some point out the negative effects of changing the course.

Junior Pierre Llorach, who took Western Civilization last year, said, “Because it’s now an AP class, they expect so much more out of the students [like learning] everything in a shorter amount of time.”

Llorach noted that more students seem to be cramming information rather than learning it. “I don’t think it’s that [the students] don’t care about learning history, but everyone is just so concerned with AP and getting credits that they’re cramming everything so they can get [a good] score,” he said.

Braunstein said, “The new course has shifted the focus from really learning and appreciating the history to memorizing facts that might be on some artificial test. Western Civilization was a healthier class. It was more fun.”

Current AP European History student Matthew Trost is considering not taking AP US History his junior year. He said, “Having to memorize names and dates detracts from the course.”

Trost said, “The class has become AP-centered, and the students have become AP-centered.” He believes that the students are learning but disagrees with the “objective” of the new course.

Trost said of those who joined the class not knowing what was in store, “Their initial motive could have been the AP [benefits], but it doesn’t matter because they’re in it now and learning whether they intended to or not.”

Braunstein pointed out that “there was a drop-off in kids who signed up because of the AP title.” She also expressed concern that students are becoming “AP-obsessed.”

Although many avoided the course after it became an AP class, some students are taking AP European History because of the change.

Sophomore and current AP European History student Adam Rosenduft said, “I took AP European History because I wanted to get the highest GPA possible to maximize my chances of getting into the college of my choice. If [AP European History] weren’t a five-point class, I wouldn’t take it because it would just be extra work that you wouldn’t get anything out of except experience and college preparation.”

Rosenduft said that the class was harder than he had expected, and he is currently taking AP European History and AS Chemistry to maximize his GPA.

Waller said, “The pass rate for AP European History will reflect the high quality of work we see in these classes.”

Many students are finding the course to be challenging, but Waller reminded them that “it’s not over yet.”

After all, this is the first year that the course is being taught, and some initial confusion was expected. Garvey said, “I would imagine that after this full year of teaching the three of us will get together and discuss what did work and what didn’t and make adjustments.”

“Every course in general takes about 3 to 5 years to get [settled],” said Braunstein.

Garvey said, “In the 12 years I’ve taught Western Civilization, I’ve never taught it the same way twice.”