This year’s “Nation’s Report Card” showed the largest drop nationally in student math scores as well as significant drops in reading, stirring debate amongst educators and community leaders.

The results, issued by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) on Oct. 24, are based on tests taken last academic year by fourth and eighth graders in all U.S. states. The results are used by educators and policymakers to assess the success of the education system. The state of California placed three points behind the national average.

The results of California’s Smarter Balanced test were released the same day and showed similar declines. In fact, it had the largest decline in scores for math from the previous test in 2019, as well as a significant drop in reading scores.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a news release that emphasized the money that the state of California is providing to help improve education and address learning loss. In 2022, $7.9 billion was allocated for what is known as Learning Block Recovery Grants. This money is funding mental health services, tutoring, extensions to the school year, and other enrichment programs.

Many have cited the COVID-19 pandemic as a cause for the decline in results. While the declining trend began before the pandemic, learning on Zoom had an impact on students’ academic performance.

“At one point, I just went into the [school Zoom] meetings and would just mute the teacher and do something else. And that kind of ruined how I learned. It’s made it harder for me to learn now because I wasn’t getting myself into the habit of doing that,” said sophomore Louis Mascari Dumont.

It’s hard to get rid of these habits after reinforcing them for so long. They present themselves in ways other than just paying attention.

“It also impacted how I did homework. I would procrastinate a lot. And then I’d do my homework at the very last second. And that’s what I’ve been doing in high school now too,” Mascari Dumont said.

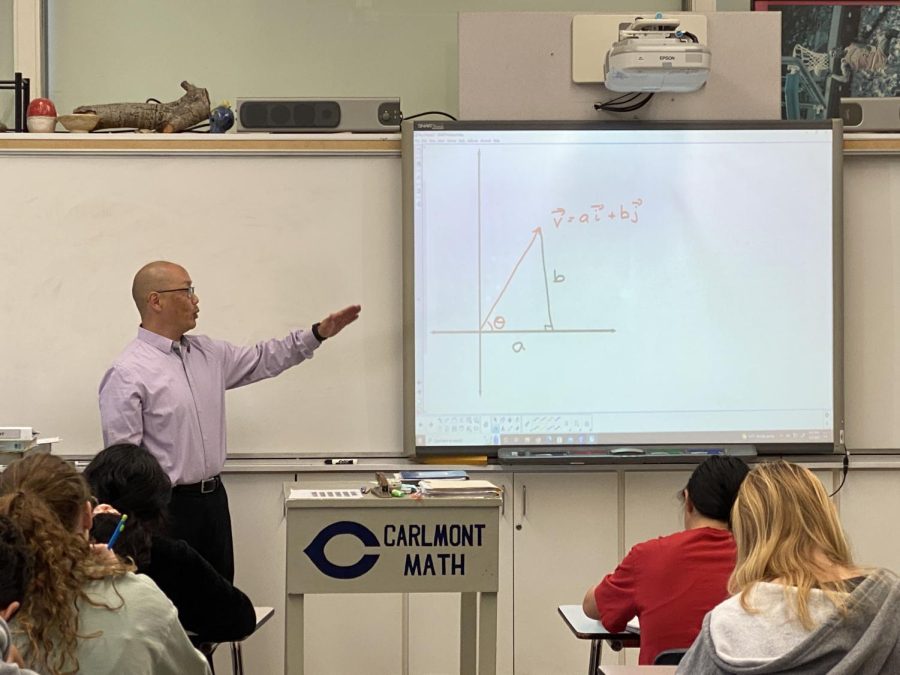

It’s a testament to the struggle that students are experiencing in school now that they are learning in person. However, Carlmont math teacher Robert Tsuchiyama thinks that distance learning itself may not have been the primary cause for the academic setbacks.

“The pandemic caused increased anxiety. And when you have all that anxiety, it’s so much more difficult to learn. So it wasn’t the distance learning situation. There’s the increased anxiety, the loneliness factor, and being isolated at home,” Tsuchiyama said. “Last year, we had students working in groups, and sometimes they were completely quiet … A year off, and they felt uncomfortable with little skills like that.”

The downward trend began before the pandemic and is correlated with downward trends in youth mental health, with 36.7% of adolescents aged 12-17 reporting that they experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Fortunately, Tsuchiyama thinks that Carlmont is recovering well from the learning gaps and that teachers and students are putting in the extra effort to catch up.

Tsuchiyama also said his wife, Shari Tsuchiyama, an elementary school teacher, has noticed significant gaps in learning and social skills in third-grade students, reinforcing the results shown with elementary school students.

Ana Homayoun, a Bay Area-based educational consultant and author of several books on adolescent development and education, has seen the decline in academic performance first-hand.

“We’ve found students struggling because of gaps in math, in part because learning online or with hybrid class schedules didn’t always cover material in the same way. We’ve also found noticeable gaps in writing skills and world languages, where students are consistently coming in for extra support,” Homayoun said. “Just yesterday, I worked with an eighth-grade boy who was overwhelmed and upset.”